Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Continuity in a Transition Year

By

By

Mike Koehler[1]*

With the election of Donald Trump as President, and based on citizen Trump’s prior blunt statement that the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) is a “horrible law and it should be changed,”[2] some apprentice commentators predicted that the FCPA was “likely to be substantially weakened, perhaps even repealed” and that “the era of vigorous FCPA enforcement . . . [was] over.”[3] However, those hyperventilating regarding the FCPA’s future were encouraged to take a deep breath, focus on facts and enforcement fundamentals, and realize that the FCPA was not going away and that FCPA enforcement was not going to substantially change. While 2017 enforcement did not eclipse 2016’s record breaking year of enforcement[4] (after all, records can’t be broken every year), this Article highlights that in 2017 there was a continuation of robust FCPA enforcement by the Trump administration involving the same enforcement theories and same resolution vehicles used in prior administrations.

Like prior years, 2017 was notable for enforcement actions against business organizations across a wide industry spectrum, involving conduct around the globe, and ranging from egregious instances of corporate bribery executed at the highest levels of the company and involving hundreds of millions of dollars to garden variety allegations of sports tickets, internships for family members of alleged foreign officials, and charitable donations.[5] Additionally, 2017 was also notable for enforcement agency policy and related developments including the Department of Justice’s announcement of an “FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy.”[6] This Article, part of a continuing yearly analysis of FCPA enforcement and related developments, provides a detailed overview of 2017 FCPA enforcement and will be of value to anyone seeking to elevate their FCPA knowledge.

While it is beyond the scope of this article to provide a detailed summary of each 2017 enforcement action, this section highlights certain enforcement statistics from 2017 and provides historical comparisons by examining the following sources: corporate DOJ enforcement actions; corporate SEC enforcement actions; aggregate corporate enforcement actions; and individual DOJ and SEC enforcement actions. For each discrete statistical category, January 20, 2017, (the beginning of the Trump administration) is highlighted so that readers can clearly see how robust FCPA enforcement involving the same enforcement theories and same resolution vehicles of prior administrations continued in the Trump administration. This demarcation also demonstrates that the first few weeks of January 2017 witnessed an unusual amount of FCPA enforcement activity in the final days of the Obama administration.

As demonstrated in Table I, in nine corporate FCPA enforcement actions[7] in 2017, the DOJ collected approximately $845 million in net settlement amounts.

| Table I

2017 DOJ Corporate FCPA Enforcement Actions |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company

(Industry) |

Settlement Amount | Resolution Vehicle[8] | Origin[9] | Related Individual Action[10] |

| Zimmer Biomet[11]

(Medical Devices) |

$17.4M | Plea/DPA[12] | Breach of Prior Deferred Prosecution Agreement | No |

| SQM[13]

(Chemicals) (Chile) |

$15.5M | DPA | Foreign Law Enforcement Investigation/Media Reporting[14] | No |

| Rolls-Royce[15]

(Power Systems) (U.K.) |

$170M | DPA | Foreign Media Reports[16] | Yes |

| Las Vegas Sands[17]

(Hotel / Gaming) |

$7M | NPA | Civil Litigation[18] | No |

| January 20, 2017 (Start of the Trump Administration) | ||||

| Linde Gas[19]

(Gas) |

$11.2M | Declination with Disgorgement | Voluntary Disclosure | No |

| CDM Smith[20]

(Engineering and Construction) |

$4M | Declination with Disgorgement | Voluntary Disclosure | No |

| Telia[21]

(Telecommun-ications) (Sweden) |

$275M[22] | Plea / DPA[23] | Foreign Media Reporting[24] | No |

| SBM Offshore[25]

(Oil Services) (Netherlands) |

$238M[26] | Plea/DPA[27] | Voluntary Disclosure[28] | Yes |

| Keppel Offshore & Marine[29]

(Oil Services) (Singapore) |

$105.5M[30] | Plea/DPA[31] | Foreign Law Enforcement Investigation | Yes |

| TOTAL | $845M | |||

As demonstrated in Table II, in seven corporate FCPA enforcement actions in 2017, the SEC collected approximately $289 million in settlement amounts.

| Table II

2017 SEC Corporate FCPA Enforcement Actions |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company

(Industry) |

Settlement Amount | Resolution Vehicle | Origin | Related Individual Action |

| Mondelēz Int’l[32]

(Food Products) |

$13M | Administrative Action | SEC Investigation[33] | No |

| Zimmer Biomet[34]

(Medical Devices) |

$13M | Administrative Action | Breach of Prior Deferred Prosecution Agreement[35] | No |

| SQM[36]

(Chemical) (Chile) |

$15M | Administrative Action | Foreign Law Enforcement Investigation / Media Reporting[37] | No |

| Orthofix Int’l[38]

(Medical Devices) |

$6M | Administrative Action | Breach of Prior Deferred Prosecution Agreement[39] | No |

| January 20, 2017 (Start of the Trump Administration) | ||||

| Halliburton[40]

(Oil and Gas) |

$29.2M | Administrative Action | Voluntary Disclosure[41] | Yes |

| Telia[42]

(Telecomm-unications) |

$209M[43] | Administrative Action | Foreign Media Reporting[44] | No |

| Alere[45]

(Diagnostics) |

$3.8M | Administrative Action | SEC Investigation[46] | No |

| TOTAL | $289M | |||

As the demarcation in the above tables demonstrates, the first few weeks of January 2017 witnessed an unusual amount of FCPA enforcement activity in the final days of the Obama administration. This dynamic was not unique to the FCPA space—as the Wall Street Journal noted in an article titled “Obama Administration Races to Finish Probes, Writing Payments From Firms:”

The Obama administration rushed to complete a raft of investigations of big business before relinquishing power, reaching settlements worth around $20 billion in the past week alone with megabanks, auto makers, drug companies and others.

The settlements—involving allegations of wrongdoing ranging from misdeeds during the financial crisis to emissions cheating, from discrimination in lending to squelching competition—are part of the usual scramble to close the books on lingering cases when a presidential administration winds down, especially when transferring control to the opposition party.[47]

In a legal system supposedly based on the rule of law, it would be nice to think that the timing of enforcement actions is not based on the career paths of the individuals occupying the seats of authority. Yet, such thinking ignores the likely reality that professional aspirations indeed explain the unusual amount of FCPA and related enforcement actions during the first few weeks of January 2017. For instance, the above-highlighted DOJ enforcement action against Las Vegas Sands was announced literally in the final hours of the Obama administration and was based on the same core conduct alleged in the SEC’s April 2016 against the company.[48] Parallel DOJ and SEC FCPA enforcement actions against issuers based on the same core conduct are rather common. However, such actions are typically coordinated and announced on the same day and the Las Vegas Sands enforcement action represents what is believed to be the only instance in FCPA history in which the DOJ and SEC enforcement actions were separated (in this matter by approximately nine months).[49] Adding to the intrigue, Sheldon Adelson (founder, chairman, and chief executive officer of Las Vegas Sands) was a major Republican contributor during the 2016 election and was in Washington, D.C. for Trump’s inauguration on the same day the DOJ enforcement action was announced.[50]

As the demarcation in the above tables also clearly demonstrates, robust FCPA enforcement involving the same enforcement theories and same resolution vehicles has continued in the Trump administration. This enforcement has occurred despite the predictions of some apprentice commentators that during the Trump administration the FCPA “[was] likely to be substantially weakened, perhaps even repealed” and that “the era of vigorous FCPA enforcement . . . [was] over.”[51] For instance, mere hours after Trump’s victory on November 8, 2016, Harvard Law Professor Matthew Stephenson wrote:

Like many people, both here in the US and across the world, I was shocked and dismayed by the outcome of the US Presidential election. To be honest, I’m still in such a state of numb disbelief, I’m not sure I’m in a position to think or write clearly. And I’m not even sure there’s much point to blogging about corruption. As I said in [a prior post], the consequences of a Trump presidency are potentially so dire for such a broad range of issues—from health care to climate change to national security to immigration to the preservation of the fundamental ideals of the United States as an open and tolerant constitutional democracy—that even thinking about the implications of a Trump presidency for something as narrow and specific as anticorruption policy seems almost comically trivial. But blogging about corruption is one of the things I do, and to hold myself together and try to keep sane, I’m going to take a stab at writing a bit about the possible impact that President Trump will have on US anti[-]corruption policy, at home and abroad. I think the impact is likely to be considerable, and uniformly bad:

Perhaps a law professor in a self-described “state of numb disbelief” and not in a “position to think or write clearly” should decline to hit the publish button. But that did not happen, and reflective of the troubled state of “news” in this modern era, and perhaps due to the institutional affiliation of the law professor (i.e. a Harvard Law Professor can’t possibly be wrong), the above doom and gloom predictions soon became a narrative that spread like wildfire.[53]

This author however, days after the 2016 elections, encouraged all to take a deep breath regarding FCPA enforcement in the Trump administration and focus on facts and not speculative narratives. Among other things, the following salient points were highlighted:

To his credit, one year after making the above “doom and gloom predictions” (and with much FCPA enforcement still to occur in 2017) Professor Stephenson publicly admitted that he was “totally wrong” or “mostly wrong” as to his predictions.[54] Around the same general time, Wall Street Journal Risk and Compliance reported the following:

[FCPA Unit Chief Daniel Kahn] dismissed the suggestion that President Donald Trump’s previous criticism of the FCPA has had any effect on the department’s enforcement of the law. Mr. Kahn said he “spanned both administrations,” referring to Mr. Trump’s predecessor, President Barack Obama, adding, “I am continuing to do what I do.”[55]

This statement from the head of the DOJ’s FCPA unit echoed previous comments from DOJ officials early in the Trump administration. For instance, in April 2017 the DOJ’s Acting Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General stated that “the [DOJ] remains committed to enforcing the FCPA and to prosecuting fraud and corruption more generally.”[56] Shortly thereafter, Attorney General Jeff Sessions stated: “We will continue to strongly enforce the FCPA and other anti-corruption laws.”[57]

Even so, what some have referred to as “Trump Derangement Syndrome”[58] continued to appear in certain FCPA commentary in 2017. For instance, when the Trump administration brought its first two corporate FCPA enforcement actions against Linde and CDM Smith in quick succession during the summer of 2017, some were aghast that the enforcement actions were resolved via so-called “declination with disgorgement” agreements.[59] A commentator stated:

What’s frustrating is that we don’t really know how Linde or CDM Smith met the criteria of the [2016] Pilot Program; or why meeting the criteria resulted in no prosecution, when under the Obama Administration a company might have received a deferred-prosecution agreement or some amount of penalties. Did these companies handle their FCPA violations in some fundamentally better way? Or have prosecutors in the Trump Administration fundamentally changed their tune, in favor of no corporate prosecutions?

. . . .

. . . If we can’t identify what these companies did right, we can’t determine how to emulate that behavior—or whether we can adopt the cynical view that the Trump Administration just isn’t interested in prosecuting corporations any more . . . .

. . . .

I’m not arguing that the Trump Administration needs to punish all FCPA violations at the more severe levels we saw during the Obama Administration. It doesn’t. There are plenty of good arguments for declinations. But we don’t have any arguments right now; just declination letters with generic language that the company met the criteria of the FCPA Pilot Program.[60]

Noticeably absent from the commentator’s rant were the following facts (facts perhaps inconvenient if one is trying to spin a narrative that FCPA enforcement was changing in the Trump administration):

“Doom and gloom” narratives aside, facts actually matter and as the above tables clearly demonstrate robust FCPA enforcement involving the same enforcement theories and the same resolution vehicles has continued in the Trump administration. Indeed, as highlighted in Tables III and IV below, corporate FCPA enforcement by the DOJ in 2017 (measured both in terms of the number of core actions and aggregate settlement amount), while lower than 2016’s record-breaking year of enforcement, was consistent with historical averages.

| Table III

Corporate DOJ FCPA Enforcement Actions (2010–2017)[61] |

|

|---|---|

| Year | Core Actions |

| 2017 | 9 |

| 2016 | 13 |

| 2015 | 2 |

| 2014 | 7 |

| 2013 | 7 |

| 2012 | 9 |

| 2011 | 11 |

| 2010 | 17 |

| Table IV

Corporate DOJ FCPA Enforcement Action Settlement Amounts (2010–2017)[62] |

|

| Year | Settlement Amounts |

| 2017 | $845M |

| 2016 | $1.34B |

| 2015 | $24.2M |

| 2014 | $1.25B |

| 2013 | $420M |

| 2012 | $142M |

| 2011 | $355M |

| 2010 | $870M |

Similarly, as highlighted in Tables V and VI below, corporate FCPA enforcement by the SEC in 2017 (measured both in terms of the number of core actions and aggregate settlement amount), while again lower than 2016’s record-breaking year of enforcement, was also relatively consistent with historical averages.

| Table V

Corporate SEC FCPA Enforcement Actions (2010–2017)[63] |

|||

| Year | Actions | ||

| 2017 | 7 | ||

| 2016 | 24 | ||

| 2015 | 9 | ||

| 2014 | 7 | ||

| 2013 | 8 | ||

| 2012 | 8 | ||

| 2011 | 13 | ||

| 2010 | 19 | ||

| Table VI

SEC FCPA Enforcement Action Settlement Amounts (2010–2017)[64] |

|||

| Year | Settlement Amounts | ||

| 2017 | $289M | ||

| 2016 | $1.07B | ||

| 2015 | $114M | ||

| 2014 | $327M | ||

| 2013 | $300M | ||

| 2012 | $118M | ||

| 2011 | $148M | ||

| 2010 | $530M | ||

Analyzing DOJ and SEC FCPA enforcement data separately in Tables I-VI above is informative given that the DOJ and SEC are separate law enforcement agencies and different issues may arise in DOJ and SEC FCPA enforcement actions.[65] On the other hand, analyzing DOJ and SEC FCPA enforcement data in the aggregate is also informative because it provides a more holistic view of FCPA enforcement.

As highlighted in Table VII, in 2017 the DOJ and SEC together collected approximately $1.13 billion in thirteen core corporate enforcement actions. The table also compares aggregate figures to historical figures and highlights unique circumstances that may have significantly skewed enforcement data in any particular year.

| Table VII

Corporate FCPA Enforcement Actions (2007–2017)[66] |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Core Actions | Settlement Amounts | Of Note |

| 2007 | 15 | $149M | Six enforcement actions involved Iraq Oil for Food conduct and these enforcement actions comprised 40% of all enforcement actions and approximately 50% of the $149 million amount. |

| 2008 | 10 | $885M | The $800 million Siemens enforcement action comprised approximately 90% of the $885 million amount. |

| 2009 | 11 | $645M | The $579 million KBR / Halliburton Bonny Island, Nigeria enforcement action comprised approximately 90% of the $645 million amount. |

| 2010 | 21 | $1.4B | Six enforcement actions, all resolved on the same day, involved various oil and gas companies’ use of Panalpina in Nigeria. Panalpina also resolved an enforcement action on the same day.

Two enforcement actions (Technip and Eni/Snamprogetti) involved Bonny Island conduct. In other words, there were 14 unique corporate enforcement actions in 2010. Of further note, the two Bonny Island enforcement actions, Technip ($338 million) and Eni/Snamprogetti ($365 million) comprised approximately 50% of the $1.4 billion amount. |

| 2011 | 16 | $503M | The $219 million JGC Corp. enforcement action involved Bonny Island conduct and comprised approximately 44% of the $503 million amount. |

| 2012 | 12 | $260M | No enforcement actions significantly skewed the statistics. |

| 2013 | 9 | $720M | The $398 million Total enforcement action comprised approximately 55% of the $720 million amount. |

| 2014 | 10 | $1.6B | Two enforcement actions (Alstom at $772 million and Alcoa at $384 million) comprised approximately 72% of the $1.6 billion amount. |

| 2015 | 11 | $139M | No enforcement actions significantly skewed the statistics. |

| 2016 | 27 | $2.41B | Three enforcement actions (Teva, Odebrecht/Braskem and VimpelCom) comprised approximately 56% of the $2.41 billion amount and five enforcement actions (the three mentioned above plus JP Morgan and Embraer) comprised approximately 72% of the amount. |

| 2017 | 13 | $1.13B | Two enforcement actions (Telia and SBM Offshore) comprised approximately 65% of the $1.13 billion amount and four enforcement actions (the two mentioned above plus Rolls-Royce and Keppel Offshore & Marine) comprised approximately 88% of the amount. |

| Total | 155 | $9.9B | |

Once again, “doom and gloom” narratives aside about the future of FCPA enforcement in the Trump administration, the above tables clearly demonstrate that robust FCPA enforcement involving the same enforcement theories and same resolution vehicles has continued in the Trump administration.

As to the same enforcement theories, Table VIII below highlights the alleged “foreign officials” in 2017 corporate enforcement actions. In terms of background, the legislative history is clear that the recipient category Congress had in mind when enacting the FCPA was bona fide foreign government officials such as Presidents, Prime Ministers, and other heads of state.[67] However, in 2017 like in prior years, FCPA enforcement actions did not always involve such “foreign officials,” but rather individuals deemed “foreign officials” under creative enforcement theories not subjected to any meaningful judicial scrutiny.

| Table VIII

“Foreign Officials” Alleged in 2017 Corporate Enforcement Actions |

|

|---|---|

| Enforcement Action | Alleged “Foreign Officials”[68] |

| Mondelēz International | Indian government officials to obtain licenses and approvals for a chocolate factory |

| Zimmer / Biomet | Mexico customs officials |

| SQM | Chilean politicians, political candidates, and individuals connected to them |

| Orthofix International | Doctors employed at government-owned hospitals |

| Las Vegas Sands | The enforcement action concerned the transfer of approximately $60 million to a Consultant for the purpose of promoting Sands’ business and brands. According to the DOJ: “Several of Sands’ contracts with and payments to Consultant had no discernible legitimate business purpose, Sands senior executives were repeatedly warned about the Consultant’s dubious business practices and the high risk of Sands’ transactions with Consultant [including those involving Chinese SOEs].” |

| Rolls-Royce | Individuals at PTT Public Company Ltd. [a Thai state-owned and state-controlled oil and gas company, which owned extensive submarine gas pipelines in the Gulf of Thailand, and was controlled by the Thai government and performed government functions that the Thai government treated as its own]

Individuals at Petrobras [a corporation in which the Brazilian government directly owned a majority of common shares with voting rights, while additional shares were controlled by the Brazilian Development Bank and Brazil’s Sovereign Wealth Fund] Individuals at Asia Gas Pipeline [AGP a joint venture between Kazakh and Chinese state-owned and state-controlled entities that was designed to transport gas through a pipeline between Kazakhstan and China. AGP was controlled by the Kazakh and Chinese governments and performed government functions for Kazakhstan and China] Individuals at SOCAR [the Azeri state-owned and state-controlled oil and gas company] Individuals at SOC [South Oil Company, an Iraqi state-owned and state-controlled oil company] Individuals at Sonangol [an Angolan state-owned and state-controlled oil company] |

| Linde Gas | Officials at the National High Technology Center (NHTC) of the Republic of Georgia, a 100% state-owned and-controlled entity |

| CDM Smith | Officials in the National Highways Authority of India (“NHAI”), India’s state-owned highway management agency |

| Halliburton | Sonangol official |

| Telia | An Uzbek government official, and a relative of a high-ranking Uzbek government official, with influence over decisions made by the Uzbek Agency for Communications and Information (“UzACI”) – this individual has been widely reported to be Gulnara Karimova] |

| Alere | Individuals associated with a “set of entities known as an Entidad Promotora de Salud, or EPS, which provided health insurance services for their members. These entities were created by Colombian law as part of the Colombian government’s efforts to provide universal health benefits to its citizens. Under this system, EPSs were responsible for organizing and guaranteeing the provision of health services for their enrolled participants and managing their participants’ health risks. Among other things, EPSs contracted for health services on behalf of their participants through a network of public, private, and their own health service providers. EPSs were both private and government controlled.” |

| SBM Offshore | “State-owned oil companies in Brazil, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Kazakhstan, Iraq and elsewhere”

Petrobras officials Angolan officials within Sonangol and Sonusa. [Sonusa refers to Sonangol USA Co. which is described as a Houston-Texas based company that is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Sonangol described as a state-owned and state-controlled oil company. Sonusa was controlled by the Angolan government and performed government functions for Angola.] Equatorial Guinean officials within GEPetrol and MMIE. GEPetrol is described as the national oil company of Equatorial Guinea, controlled by the country’s Ministry of Mines, Industry and Energy [MMIE] and performed government functions for Equatorial Guinea. KazMunayGas officials at least one Company 1 employee. [KazMunayGas is described as Kazakhstan’s state-owned and state-controlled oil company, controlled by the Kazakh government that performed government functions. Company 1 is described as a subsidiary of an Italian oil and gas company in which the government of Kazakhstan granted the company a concession as the operator of the Kashagan oil field development in Kazakhstan. In this capacity, Company 1 was acting in an official capacity for or on behalf of KazMunayGas in awarding contracts]. Iraqi officials within SOC. [SOC is described as South Oil Company, an Iraqi state-owned and state-controlled oil company, controlled by the Iraqi government that performed government functions. |

| Keppel Offshore | Brazilian Official 1 [described as an employee of Petrobras], Brazilian Official 2 [described as an employee of Petrobras] and the Worker’s Party [described as a political party in Brazil]. |

As demonstrated by the above table, of the thirteen corporate enforcement actions in 2017, seven (54%) involved, in whole or in part, employees of alleged state-owned or state-controlled entities (“SOEs”) with an additional two actions (15%) involving, in whole or in part, individuals associated with foreign health care systems.

The SBM Offshore enforcement action is worthy of additional discussion because buried deep within the approximately one hundred seventy pages of resolution documents was a notable “foreign official” theory.[69] The notable theory was likely not a significant factor in the overall resolution of the matter (after all, the conduct at issue “lasted over 16 years, was carried out by employees at the highest level of the organization, including two high-level executives who were at times directors of a wholly-owned U.S. domestic concern, involved large bribe payments, and included deliberate efforts to conceal the scheme”).[70] Even so, there are two ways to look at such non-determinative allegations in FCPA enforcement actions: (1) either the DOJ (or SEC) are practicing their typing skills; or (2) the DOJ (or SEC) are using the enforcement action to send a message to the business community, regarding their FCPA interpretations. The best answer is probably the latter, and as demonstrated in the above chart, the DOJ alleged that: (1) Sonusa (a Texas-incorporated, Texas-based company) was an “instrumentality” of the Angolan government; and (2) a subsidiary of an Italian oil and gas company was an “instrumentality” of the Kazakh government because it was granted a concession by the Kazakh government and was thus “acting in an official capacity for or on behalf” of the Kazakh government.[71] In United States v. Castle, the Fifth Circuit correctly noted that “foreign officials” were a “well-defined group of persons.”[72] However, the breadth of the above type of “foreign official” allegations are practically boundless.

In addition to the same FCPA enforcement theories and resolution vehicles continuing in the Trump administration, certain concerning enforcement statistics have also continued such as: (1) much of the largeness of corporate enforcement resulted from actions against foreign companies; (2) the continued prominence of NPAs, DPAs, and other alternative resolution vehicles to resolve corporate FCPA enforcement actions; and (3) the continued lack of related individual prosecutions in connection with most corporate enforcement actions.

The first concerning statistic from 2017 corporate FCPA enforcement was, consistent with prior years,[73] much of the largeness of corporate enforcement resulted from actions against foreign companies. Specifically, of the thirteen corporate enforcement actions from 2017, five (approximately 40%) were against foreign companies (based in many instances on the mere listing of securities on U.S. markets and in a few instances on sparse allegations of a U.S. nexus in furtherance of an alleged bribery scheme).[74] Even more dramatic, of the net $1.13 billion FCPA settlement amounts from 2017 corporate enforcement actions, approximately 90% was from enforcement actions against foreign companies.[75]

With one exception (Keppel Offshore—Singapore), all of the foreign companies that resolved 2017 FCPA enforcement actions were headquartered in countries that, like the U.S., are parties to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (“OECD”) and Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions (OECD Convention).[76] The issue thus arises whether these FCPA enforcement actions represented a proper use of the FCPA—at least from a policy standpoint. In other words, what legitimate U.S. law enforcement interests are implicated when for example:

Chile, the U.K., Sweden, and the Netherlands are all “peer” countries with mature FCPA-like laws governing the conduct of their companies coupled with reputable legal systems to prosecute such offenses. Given this reality, as well as the specific provision in Article 4 of the OECD[77] Convention that “[w]hen more than one Party has jurisdiction over an alleged offence described in this Convention, the Parties involved shall, at the request of one of them, consult with a view to determining the most appropriate jurisdiction for prosecution,”[78] can it truly be said that the U.S. was the most appropriate jurisdiction to prosecute certain foreign companies for alleged interactions with non-U.S. officials?

In this regard, the $30.5 million SQM enforcement action is worth contemplating as the U.S. enforcement action against the Chilean company lacked any U.S. nexus other than SQM having a form of American Depository Shares listed on the New York Stock Exchange.[79] Further, the problematic conduct was exclusively focused on the Chilean company’s conduct with Chilean officials, including political donations made by the company to Chilean politicians and candidates.[80] When thinking about FCPA enforcement actions against foreign companies based on sparse U.S. jurisdictional allegations, it is useful to think about the “flip side” of the action. The “flip side” of the SQM enforcement action would be Chile law enforcement bringing an enforcement action against a U.S. company for its interactions, including political contributions, with U.S. officials premised solely on the U.S. company listing certain of its securities on a Chilean stock exchange. Is the U.S. prepared for such a foreign prosecution of a U.S. company given that some in the world view certain aspects of the U.S. political system to be corrupt?

Even the DOJ seems to recognize the public policy issues associated with FCPA enforcement actions against foreign companies. For instance, Sandra Moser (Principal Deputy Chief of the DOJ’s Fraud Section) stated in 2017 that the DOJ is “working harder than ever to coordinate with global partners and avoid what some have termed ‘piling on’ in attendant global resolutions.”[81] She further stated:

Coordination with foreign countries will continue, and that number of coordinated resolutions will grow, including with new countries. This is important for several reasons. First and foremost, it is fair to companies. It encourages companies to cooperate across the board, because we understand that, at the end of a case, money paid out is derived from one pie. A resolving company should not have piled upon it duplicative fines via separate resolutions that do not credit one another. Although the ‘piling on’ problem is not entirely solved by doing this (other countries may certainly try to reach additional resolutions), our efforts do mitigate this problem, and we are trying to do better in this regard.[82]

In most of the 2017 enforcement actions against foreign companies highlighted above there were credits or offsets in terms of U.S. FCPA settlement amounts for related foreign law enforcement actions.[83] However, the broader issue is whether the U.S. should have simply backed away from these enforcement actions because of the related foreign law enforcement action. For instance, an FCPA practitioner rightly observed that “[n]on-U.S. efforts to prosecute overseas bribery are hampered by the absence of clear, credible statements from U.S. prosecutors that they will desist from prosecuting if a local prosecutor does so in good faith.”[84] The practitioner further explained:

This matters because of the baleful, disruptive effect a U.S. prosecution has on efforts elsewhere. Simply put, U.S. prosecutors have powers that most of their European counterparts can only dream of: unfettered discretion, virtual absence of judicial control over investigations and negotiated outcomes, expansive views of their extraterritorial powers coupled with the fact that more than eighty percent of international business deals are denominated in U.S. dollars, very helpful laws on corporate criminal responsibility, the risk of huge corporate penalties and the ability to cumulate such penalties, investigations that last months rather than multiple years, powers of evidence-gathering from which corporations are virtually helpless in shielding incriminating information, virtual freedom from any double jeopardy/ne bis in idem constraints, and flexible procedures such as DPAs and NPAs—all enable them to move more quickly, and to strike far more terror into the hearts of corporate decision-makers, than can European prosecutors.

. . . .

This situation could lead to trouble. The “level playing field” that the OECD Convention envisioned was not only a world in which companies of all nationalities faced the same prohibitions and comparable risks of prosecution, but in which prosecutors would have an equal say in outcomes. Given the relative ineffectiveness of many countries’ efforts, the fact that the U.S. prosecutors have attempted to fill this gap is neither surprising nor, in itself, wrong. But there are already indications of resentment [in various countries]. . . .[85]

In the minds of some,[86] FCPA enforcement has become a convenient cash cow for the U.S. government and the numerous (and large) 2017 enforcement actions against foreign companies, which resulted in approximately $1 billion flowing into the U.S. treasury,[87] only amplify these concerns.

From a historical perspective, it is worth noting that part of the FCPA reform discussion in the 1980’s were bills introduced by Democrats seeking to waive the FCPA’s provisions in the case of any country which the Attorney General had certified as having “(1) effective bribery or corruption statutes; and (2) an established record of aggressive enforcement of such statutes.”[88] While waiving the FCPA’s provisions—as those bills sought to do—does not seem like a good idea, perhaps the time has come with the maturity of the OECD Convention for U.S. enforcement agencies to adopt a policy of not bringing FCPA enforcement actions against foreign companies from peer OECD Convention countries.

The second concerning statistic from 2017 corporate FCPA enforcement was that, consistent with the trend in the FCPA’s modern era, 100% of corporate enforcement actions included a DOJ NPA, DPA, or declination with disgorgement agreement or an SEC administrative action.[89] The common thread in all of these alternative resolution vehicles is the lack of meaningful judicial scrutiny. This is ironic because the FCPA enforcement agencies often preach about the rule of law and how law enforcement should be characterized by consistency and predictability.[90] For instance, in 2017 the DOJ’s Deputy Assistant Attorney General Rod Rosenstein stated: “The term ‘rule of law’ refers to the principle that the United States is governed by law and not arbitrary decisions of government officials. Rule of law systems are characterized by consistency and predictability.”[91]

Moreover, in 2017 Rosenstein stated: “Corporate enforcement and settlement demands must always have a sound basis in the evidence and the law. We should never use the threat of federal enforcement unfairly to extract settlements.”[92]

Yet, in the minds of many, the alternative resolution vehicles used in certain corporate FCPA enforcement actions are used to extract settlements[93] and arbitrary decisions of government officials that lack consistency and predictability have been part of the FCPA conversation nearly as long as the FCPA itself. For instance, one of the best things ever written about the FCPA was penned by Robert Primoff, who stated:

The government has the option of deciding whether or not to prosecute. For practitioners, however, the situation is intolerable. We must be able to advise our clients as to whether their conduct violates the law, not whether this year’s crop of administrators is likely to enforce a particular alleged violation. That would produce, in effect, a government of men and women rather than a government of law.[94]

Although this observation was from 1982, the more things change the more they stay the same. The above comment applies with equal or greater force in the FCPA’s modern era and is relevant to a development discussed in the next section (i.e., the DOJ announcing yet another non-binding FCPA enforcement policy).[95]

The third concerning statistic from 2017 corporate FCPA enforcement is the general lack of individual enforcement actions in connection with most corporate enforcement actions.[96] Specifically, of the nine DOJ corporate enforcement actions in 2017, six (67%) lacked (thus far any related DOJ charges against company employees.[97] Similarly, of the seven SEC corporate enforcement actions in 2017, six (86%) lacked (thus far) any related SEC charges against company employees.[98] These 2017 enforcement statistics are generally consistent with historical averages given that approximately 80% of DOJ and SEC corporate enforcement actions since 2006 have not resulted in any related DOJ charges against company employees.[99]

These statistics are all the more troubling given the DOJ’s and SEC’s frequent rhetoric about the importance of individual prosecutions. For instance, in 2017 DOJ enforcement officials stated: “[the DOJ is committed to holding] individuals accountable for criminal activity” and that “[e]ffective deterrence of corporate corruption requires prosecution of culpable individuals. [The DOJ] should not just announce large corporate fines and celebrate penalizing shareholders.”[100]

Likewise, SEC enforcement officials stated in 2017:

[C]ompanies cannot engage in bribery without the actions of culpable individuals. The Enforcement Division is broadly committed to holding individuals accountable when the facts and the law support doing so . . . individual accountability drives behavior more than corporate accountability, a point which is supported by both logic and experience. The Division of Enforcement considers individual liability in every case it investigates; it is a core principle of our enforcement program.[101]

In 2017, the DOJ’s Rosenstein stated: “the [DOJ’s] rhetoric gets a lot of attention—the policy memos and speeches. But performance is what matters most.”[102] Indeed, actions do speak louder than words, and similar to prior years, the DOJ’s and SEC’s rhetoric regarding individual prosecutions, at least as measured against corporate enforcement actions, remains hollow as demonstrated by the above statistics.

The statistics highlighted above regarding the notable gap between corporate FCPA enforcement actions and related individual enforcement against company employees was not meant to suggest that the DOJ or SEC do not bring individual FCPA enforcement actions. The next section profiles 2017 DOJ and SEC individual FCPA enforcement actions (including historical comparisons) and highlights the noticeable increase in DOJ individual enforcement actions compared to historical averages.

As demonstrated in Table IX, in 2017 the DOJ filed or announced FCPA criminal charges against eighteen individuals.

| Table IX

2017 DOJ Individual FCPA Enforcement Actions |

||

|---|---|---|

| Individuals | Employer/Former Employer | Related Corporate Enforcement Action |

| Juan Hernandez[103]

Charles Beech Fernando Ardila[104] |

Associated with various privately-held energy companies | No |

| Joo Hyun Bahn[105]

Ban Ki Sang San Woo |

A commercial real estate project involving Keangnam Enterprises Co. Ltd | No |

| Joseph Baptiste[106] | Haitian focused non-profit | No |

| Keith Barnett[107]

Andreas Kohler James Finley Aloysius Zuurhout Petros Contoguris |

Rolls Royce | Yes |

| Anthony Mace[108]

Robert Zubiate |

SBM Offshore | Yes |

| Chi Ping Patrick Ho[109]

Cheikh Gadio |

Associated with China Energy Fund Committee, CEFC China Energy Company Limited | No |

| Colin Steven[110] | Embraer | Yes |

| Jeffrey Chow[111] | Keppel Offshore & Marine | Yes |

As demonstrated by Table X, the number of DOJ individual FCPA enforcement actions in 2017 was significantly above historical averages.

| Table X

DOJ Individual FCPA Enforcement Actions (2007–2017)[112] |

|

| Year | Individuals Charged with Criminal FCPA Offenses |

| 2017 | 18 |

| 2016 | 8 |

| 2015 | 8 |

| 2014 | 10 |

| 2013 | 12 |

| 2012 | 2 |

| 2011 | 10 |

| 2010 | 33

(including 22 in the manufactured Africa Sting case) |

| 2009 | 18 |

| 2008 | 14 |

| 2007 | 7 |

At first blush, it appears from Table X above that the DOJ brought numerous individual enforcement actions in 2017 when the reality is that the bulk of these actions were clustered around just a few core sets of facts. This observable fact is consistent with prior years as approximately 50% of individuals charged by the DOJ with FCPA criminal offenses since 2006 have been in just eight core actions.[113]

Two individual DOJ FCPA enforcement actions in 2017 are worth highlighting in greater detail. The first involved Joo Hyun Bahn, Ban Ki Sang, and San Woo, and involved a real estate project in Vietnam.[114] What made the enforcement action unusual is that the third party intended to facilitate the bribery scheme of a foreign official simply pocketed the money for himself.[115] As stated by the DOJ: “This alleged conduct proves the adage that there is truly no honor among thieves . . . . The indictment alleges that two defendants wanted to bribe a government official; instead they were defrauded by their co-defendant.”[116] The enforcement action thus serves as an important reminder that even unsuccessful bribery schemes are actionable under the FCPA.

The second notable individual enforcement action was against Anthony Mace (the former CEO of SBM Offshore). In terms of general FCPA background:

Yet, the Anthony Mace enforcement action alleged the following salient issues:

The Mace enforcement should be a required read for all business executives who have oversight authority over a company’s operations and are frequently called upon to authorize or approve various expenditures.

U.S. v. Seng represented another notable development in DOJ individual FCPA enforcement. Although this enforcement action originated in 2015, in 2017 Seng put the DOJ to its burden of proof at trial, and after a four week trial, a federal jury convicted him of two counts of violating the FCPA, one count of paying bribes and gratuities, one count of money laundering, and two counts of conspiracy “for his role in a scheme to bribe United Nations ambassadors to obtain support to build a conference center in Macau that would host, among other events, the annual United Nations Global South-South Development Expo.”[117] The trial was notable because FCPA trials are rare and the DOJ victory in Seng broke a long streak of DOJ FCPA trial court debacles between 2011 and 2015.[118]

Switching from DOJ individual enforcement to SEC enforcement, as demonstrated in Table XI below, the SEC brought FCPA civil charges against three individuals in 2017.

| Table XI

2017 SEC Individual FCPA Enforcement Actions |

||

|---|---|---|

| Individual | Employer / Former Employer | Related Corporate Enforcement Action |

| Michael Cohen

Vanja Baros[119] |

Och-Ziff | Yes |

| Jeannot Lorenz[120] | Halliburton | Yes |

As highlighted in Table XII below, the number of SEC individual FCPA enforcement actions in 2017 was generally consistent with historical averages.

| Table XII

SEC Individual FCPA Enforcement Actions (2007–2017)[121] |

|

| Year | Individuals Charged with Civil FCPA Offenses |

| 2017 | 3 |

| 2016 | 8 |

| 2015 | 2 |

| 2014 | 2 |

| 2013 | 0 |

| 2012 | 4 |

| 2011 | 12 |

| 2010 | 7 |

| 2009 | 5 |

| 2008 | 5 |

| 2007 | 7 |

As highlighted in this section, despite “doom and gloom” predictions about FCPA enforcement (and the statute itself) in the new Trump administration, robust FCPA enforcement involving the same enforcement theories and same resolution vehicles has continued in the Trump administration. As discussed next, 2017 was also notable for enforcement agency policy and related developments.

This section discusses two notable enforcement agency policy and related developments from 2017: first, the DOJ’s announcement of an “FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy”; and second, the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision rejecting the SEC’s position on the disgorgement remedy (the dominant remedy the SEC seeks in corporate FCPA enforcement actions). Finally, this section concludes by noting that 2017 was the 40th anniversary of the FCPA’s enactment and encourages readers to ponder, using certain 2017 enforcement statistics, whether the FCPA has been successful in achieving its objectives.

In late 2017, the DOJ announced a new “FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy” (CEP) representing its latest attempt (spanning over a decade) to “increase the volume of voluntary disclosures, and enhance [its] ability to identify and punish culpable individuals” by “providing additional benefits to companies based on their corporate behavior once they learn of misconduct.”[122] After providing a detailed overview of the CEP, the following issues are discussed:

For starters, the CEP is non-binding DOJ guidance. As stated by Deputy Attorney General Rosenstein: “The new policy, like the rest of the Department’s internal operating policies, creates no private rights and is not enforceable in court. . . . The new policy does not provide a guarantee. We cannot eliminate all uncertainty. Preserving a measure of prosecutorial discretion is central to ensuring the exercise of justice.”[123]

According to the DOJ, the CEP is “aimed at providing additional benefits to companies based on their corporate behavior once they learn of misconduct.”[124] In announcing the CEP, Deputy Attorney General Rosenstein stated:

The new policy enables the Department to efficiently identify and punish criminal conduct, and it provides guidance and greater certainty for companies struggling with the question of whether to make voluntary disclosures of wrongdoing.

. . . .

We expect the new policy to reassure corporations that want to do the right thing. It will increase the volume of voluntary disclosures, and enhance our ability to identify and punish culpable individuals.[125]

The above policy goals are nothing new. For over a decade, the DOJ has encouraged business organizations to voluntarily disclose conduct that may implicate the FCPA so that it can, among other things, increase prosecution of individuals.[126] For instance, the DOJ’s April 2016 FCPA Pilot Program stated:

The principal goal of [the Pilot] program is to promote greater accountability for individuals and companies that engage in corporate crime by motivating companies to voluntarily self-disclose FCPA-related misconduct . . . .

. . . .

. . . [T]his pilot program is intended to encourage companies to disclose FCPA misconduct to permit the prosecution of individuals whose criminal wrongdoing might otherwise never be uncovered by or disclosed to law enforcement.[127]

As stated by former DOJ FCPA Unit Chief Charles Duross and former DOJ FCPA Unit Assistant Chief James Koukios: “[t]he [CEP’s] elements largely track those of the Pilot Program.”[128] Likewise, others noted that “[w]hile Mr. Rosenstein characterized these revisions as ‘new policy,’ they largely restate the terms and definitions of the prior Pilot Program. . . .”[129] Nevertheless, the key features of the CEP are the following:

When a company has voluntarily self-disclosed misconduct in an FCPA matter, fully cooperated, and timely and appropriately remediated . . . there will be a presumption that the company will receive a declination absent aggravating circumstances involving the seriousness of the offense or the nature of the offender. Aggravating circumstances that may warrant a criminal resolution include, but are not limited to, involvement by executive management of the company in the misconduct; a significant profit to the company from the misconduct; pervasiveness of the misconduct within the company; and criminal recidivism.

If a criminal resolution is warranted for a company that has voluntarily self-disclosed, fully cooperated, and timely and appropriately remediated, the Fraud Section:

To qualify for the FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy, the company is required to pay all disgorgement, forfeiture, and/or restitution resulting from the misconduct at issue.

. . . .

The requirement that a company pay all disgorgement, forfeiture, and/or restitution resulting from the misconduct at issue may be satisfied by a parallel resolution with a relevant regulator (e.g., the United States Securities and Exchange Commission).[130]

Here again, the CEP’s key features of voluntary disclosure, cooperation, and remediation are nothing new as the Pilot Program contained the same key features.[131] Nevertheless, the CEP is a bit different than the previous Pilot Program which provided that when those same three steps were met the “Fraud Section’s FCPA Unit will consider a declination of prosecution.”[132] However, the difference between the CEP’s “presumption” and the Pilot Program’s “will consider” in non-binding DOJ guidance is likely slight.

Moreover, and very importantly, the “presumption” in the CEP is not a presumption that there will be no enforcement action, only that the enforcement action will take the form of disgorgement/forfeiture.[133] As alluded to above, even if a business organization engages in the three steps contemplated by the CEP and the aggravating circumstances are not present, a business organization will still be subject to an enforcement action by the DOJ, SEC, or another relevant regulatory agency to pay “all disgorgement, forfeiture, and/or restitution resulting from the misconduct at issue.”[134] This form of resolution is nothing new, as the DOJ publicly announced seven so-called “declinations” consistent with the previous Pilot Program.[135] Three of the so-called “declinations” involved issuers (Nortek, Akamai Technologies, and Johnson Controls)[136] and thus the disgorgement was satisfied by a parallel resolution with the SEC. Four of the so-called “declinations” involved non-issuers (HMT, NCH, Linde and CDM Smith) and pursuant to these resolutions the companies were required to pay disgorgement and/or forfeiture in the following amounts: $2.7 million; $335,000; $11.2 million; and $4 million.[137] In short, the notion that the CEP provides amnesty or allows a business organization to escape an enforcement action is simply false.

If certain of the aggravating circumstances are present, the CEP states:

If a criminal resolution is warranted for a company that has voluntarily self-disclosed, fully cooperated, and timely and appropriately remediated, the Fraud Section:

In this regard, the CEP is slightly different compared to the previous Pilot Program, which stated:

[I]f a criminal resolution is warranted, the Fraud Section’s FCPA Unit:

Here again however, the difference between “will” and “may / should” in non-binding DOJ guidance is likely slight.

If a business organization does not voluntarily disclose, but the DOJ learns of the organization’s alleged improper conduct, the CEP states (similar to the previous Pilot Program):

If a company did not voluntarily disclose its misconduct to the Department of Justice (the Department) in accordance with the standards set forth [elsewhere in the policy], but later fully cooperated and timely and appropriately remediated in accordance with the standards set forth [elsewhere in the policy], the company will receive, or the Department will recommend to a sentencing court, up to a 25% reduction off of the low end of the U.S.S.G. fine range.[140]

With a comprehensive understanding of the CEP, the following issues are next discussed:

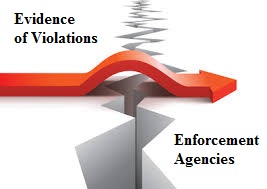

Prior to addressing the obvious logical gap in the CEP, it is important to understand the informational gap that the CEP (and prior to that the Pilot Program and prior to that, numerous DOJ pronouncements) seeks to address. This gap is best demonstrated by the below picture.

In other words, business organizations (whether through internal audits, compliance hotlines, or other means) often possess information that employees within the organization or third parties engaged by the organization may have violated the FCPA. Because business organizations generally do not have a legal obligation to disclose this information (a fact rightly recognized in the CEP and previously in the pilot program), the FCPA’s dual enforcers—the DOJ and SEC—often do not learn about potential FCPA violations.[141]As candidly stated by then Assistant Attorney General Leslie Caldwell in connection with the Pilot Program, “the DOJ is ‘confident that there are lots of FCPA violations’ that do not come to the DOJ’s attention.”[142]As a result, there are likely many FCPA violations (at least based on current enforcement theories) that occur in the global marketplace that are not disclosed to the enforcement agencies.” Because such violations (again in the eyes of the enforcement agencies) are not disclosed to the enforcement agencies, there is no enforcement action. Because there is no enforcement action, the individual or individuals engaging in the problematic conduct will not be held legally accountable. Because the individuals are not being held legally accountable, FCPA enforcement is not as effective as it could be for achieving maximum deterrence. Indeed, in announcing the CEP, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein rightly observed that “[e]ffective deterrence of corporate corruption requires prosecution of culpable individuals.”[143]

As depicted in the above picture, the FCPA enforcement landscape thus has a deep gorge, and how to bridge this gorge has long perplexed the FCPA enforcement agencies. As discussed below, encouraging voluntary disclosure of FCPA violations by business organizations has long been part of the DOJ’s FCPA talking points.

Yet, this objective suffers from an obvious logical gap in that for years the DOJ has had the opportunity to do just what the CEP (and previously the Pilot Program) seeks to accomplish. Specifically, since 2011 twenty-five corporate FCPA enforcement actions originated with voluntary disclosures.[144] However, in only five instances (20%) was there a related DOJ prosecution of a company employee.[145] Perhaps even more on point, since the April 2016 Pilot Program, the DOJ has self-identified seven corporate matters as being resolved consistent with the Pilot Program, yet not one instance resulted in a related FCPA prosecution of a company employee.[146] The DOJ’s stated objective in establishing the CEP thus seems to lack credibility for the simple fact that if the goal of the CEP is to encourage voluntary disclosures in order to permit the DOJ to prosecute company employees, then why have zero of the matters the DOJ has self-identified as being resolved consistently with the Pilot Program—and more broadly 80% of DOJ corporate actions over the past six years—not resulted in any related DOJ FCPA prosecution of company employees? Logical gaps aside, it is important to recognize, as alluded to above, that the CEP, both in terms of rhetoric and substance, is really nothing new.

To be clear, this section does not advocate or even imply that the corporate community should ignore the CEP. After all, the DOJ has extreme leverage over business organizations subject to FCPA scrutiny and it is always wise to at least be cognizant of what an adversary possessing a big and sharp stick is saying. Nevertheless, absent limited circumstances not often present in instances of FCPA scrutiny, how to respond to internal breaches of FCPA compliance policies is a business decision entrusted to those charged with managing the business organization. In exercising this business judgment, the corporate community should take the CEP with a grain of salt for the reasons described above and for the additional ten reasons described below.

First, as discussed above, the CEP is non-binding and commits the DOJ to absolutely nothing. Like prior DOJ FCPA guidance, such as the 2016 Pilot Program and the 2012 FCPA Guidance, in connection with release of the CEP Deputy Attorney General Rosenstein stated: “The new policy, like the rest of the Department’s internal operating policies, creates no private rights and is not enforceable in court.”[147]

Sure, unlike prior FCPA Guidance, the CEP is incorporated into the U.S. Attorneys’ Manual but here again it is important to highlight that the first section of the USAM (1-1.200) states:

The Justice Manual provides [only] internal DOJ guidance. It is not intended to, does not, and may not be relied upon to create any rights, substantive or procedural, enforceable at law by any party in any matter civil or criminal. Nor are any limitations hereby placed on otherwise lawful litigative prerogatives of the DOJ.[148]

Second, the notion that the CEP somehow provides immunity, a pass, or promises no enforcement action is simply false. Yet here again, certain commentators were either uninformed or suffering from Trump Derangement Syndrome. For instance, referring to the CEP Ren Steinzor (a University of Maryland law professor and member scholar at the Center for Progressive Reform) wrote:

In November 2017, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein told a group of industry executives that DOJ would not indict companies that voluntarily came forward to report violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Although he preserved “a measure of prosecutorial discretion,” his announcement was clearly intended to eliminate an Obama-era policy that required companies to come forward to share information about their employees’ illegal activities without receiving such assurances.[149]

As the above information demonstrates, the notion that the CEP represents a DOJ position not to “indict companies that voluntarily c[o]me forward to report [FCPA] violations” is clearly false and the CEP is clearly an extension of the Obama-era Pilot Program not an “elimination” of the Pilot Program.[150]

Regardless, and as highlighted above, even if a business organization does all that the DOJ wants it to do under the CEP, there is still a requirement that a “company is required to pay all disgorgement, forfeiture, and/or restitution resulting from the misconduct at issue.”[151] In short, the best a business organization can do under the CEP is an FCPA enforcement action (albeit using a recently invented and creative form) and all of the potential collateral consequences of an FCPA enforcement action (negative media coverage, reputational damage, related civil litigation, etc.) are still likely to result.

Third, even gaining the greatest benefit under the CEP (a mere requirement of a disgorgement / forfeiture enforcement action) is contingent upon a business organization meeting the DOJ’s vague concepts of “voluntary self-disclosure,” “full cooperation,” and “timely and appropriate remediation.”[152] Among other key terms or concepts that the DOJ possesses absolute, unreviewable discretion over are:

In short, even gaining the greatest benefit under the CEP (a mere requirement of a disgorgement / forfeiture enforcement action) is contingent upon a business organization meeting the DOJ’s vague concepts of various key terms. Indeed, as Deputy Attorney General Rosenstein stated: “The new policy does not provide a guarantee. We cannot eliminate all uncertainty. Preserving a measure of prosecutorial discretion is central to ensuring the exercise of justice.”[154]

Fourth, gaining the greatest benefit under the CEP is further contingent upon the DOJ not finding the existence of certain “aggravating circumstances.”[155] As stated in the CEP, these “aggravating circumstances” are non-exclusive (which in and of itself is a big deal) and may include: “involvement by executive management of the company in the misconduct; a significant profit to the company from the misconduct; pervasiveness of the misconduct within the company; and criminal recidivism.”[156]

Here again, the DOJ possesses absolute, unreviewable discretion as to the existence of “aggravating circumstances” and the DOJ has refused to provide greater clarity as to what certain key terms, such as “executive management” and “significant profit,” actually mean.[157]

Perhaps the most vague and ambiguous term is “criminal recidivism.” Does “criminal recidivism” refer to enforceability under the FCPA or any criminal statute? Regardless of the answer, does “criminal recidivism” refer to any form of DOJ resolution, such as (in addition to actual plea agreements) deferred prosecution agreements, non-prosecution agreements, and “declinations with disgorgement”? Here again, the DOJ has refused to provide greater clarity.[158]

Fifth, even if a business organization gains the greatest benefit under the CEP (a “mere” requirement of a disgorgement/forfeiture enforcement action) or failing this:

(i) because of “aggravating circumstances” a 50% reduction off of the low end of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines (U.S.S.G.) fine range; or

(ii) because of the lack of voluntary disclosure an “up to a 25% reduction off of the low end of the U.S.S.G. fine range,” the DOJ possesses extreme leverage and absolute, unreviewable discretion as to what the disgorgement/forfeiture/guidelines range amounts will be.

The reality is that this “final number” is the product of and contingent upon several less than transparent discretionary calls made by the DOJ. Indeed, as FCPA practitioners have rightly observed: “the exercise of calculating tainted profits is subjective and is the focus of considerable negotiation with the DOJ (and the SEC), often involving experts. Unsurprisingly, the government’s calculation of ‘profits’ often exceeds that of the disclosing party, and the government has substantial leverage to impose its conclusion.”[159]

Sixth, the CEP states that even if “aggravating circumstances” are present and thus a criminal resolution may be warranted that (for a company that voluntarily disclosed, fully cooperated, and timely and appropriately remediated) there will “generally” not be a requirement for “appointment of a monitor.”[160]

While this sounds significant, in reality it isn’t. In fact, very few FCPA enforcement actions in recent years against U.S. companies (as opposed to foreign companies) have required the formal appointment of a compliance monitor.[161] Nevertheless, in nearly all instances the DOJ has required, as a condition of settlement, that the company, through counsel, report to the DOJ (and SEC) throughout the 1–3 year term of the resolution agreement.[162] While this is no doubt cheaper for the company than the appointment of a formal monitor, such post-enforcement action reporting requirements can easily aggregate into the millions of dollars and the CEP is silent on this form of post-enforcement action reporting.

Seventh and implicit in the above reasons as well, for why the corporate community should take the CEP with a grain of salt is perhaps obvious but bears repeating: the DOJ is an adversary.

Imagine a business organization facing an adversary in other legal actions where the adversary possesses absolute, unreviewable discretion as to how the action will be resolved. It is doubtful that any business organization would accede to the demands of this adversary and rightly so. While the DOJ possesses bigger and sharper sticks than most legal adversaries, the two simple fact remains: (1) the DOJ is an adversary to a business organization under FCPA scrutiny, and (2) a business organization has no legal or moral obligation to assist the DOJ.[163] As Deputy Attorney General Rosenstein rightly noted: “Of course, companies are free to choose not to comply with the FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy. A company needs to adhere to the policy only if it wants the Department’s prosecutors to follow the policy’s guidelines.”[164]

In short, business managers and others making decisions on behalf of an organization need to understand that thoroughly investigating an issue, promptly implementing remedial measures, and effectively revising and enhancing compliance policies and procedures—all internally and without disclosing to the enforcement agencies—is a perfectly acceptable, legitimate, and legal response to FCPA issues in but all the rarest of circumstances.

An eighth reason why the corporate community, or at least so-called “issuers” under the FCPA, should take the CEP with a grain of salt is that it is an incomplete program because issuers are subject to FCPA enforcement by both the DOJ and SEC. However, the CEP is a DOJ program only. To be sure, just like the DOJ, the SEC has long encouraged voluntary disclosure of FCPA violations coupled with repeated assurances that voluntary disclosure will result in meaningful credit.[165] However, unless and until the SEC articulates a similar FCPA program (a program that will likely suffer from the same deficiencies as the DOJ’s program), the CEP addresses only half of the enforcement landscape facing issuers.

The ninth and perhaps the biggest reason why the corporate community should take the CEP with a grain of salt is that it only addresses a relatively minor component of the overall financial consequences to a business organization that is the subject of FCPA scrutiny and enforcement.

For obvious reasons, settlement amounts in an FCPA enforcement action tend to get the most attention. After all, settlement amounts are mentioned in DOJ/SEC press releases, press releases generate media coverage, and the corporate community reads the media. However, knowledgeable observers recognize, as depicted in the below representative picture, that FCPA scrutiny and enforcement results in “three buckets” of financial exposure to a business organization.[166]

In nearly every instance of FCPA scrutiny and enforcement, bucket #1 (pre-enforcement action professional fees and expenses) is the largest financial hit to a business organization. The reasons for this are both practical and potentially provocative.[167] In terms of the practical, all instances of FCPA scrutiny have a point of entry, for instance problematic conduct in China that then often results (if there is a voluntary disclosure) in the “where else” question from the enforcement agencies which often prompts the company under scrutiny to conduct a much broader review of its business operations. In terms of the provocative, FCPA scrutiny arising from voluntary disclosure can easily become a billing boondoggle for FCPA Inc. participants.

A couple of specific examples highlight how extensive pre-enforcement action professional fees and expenses can become.

For instance, Avon resolved an FCPA enforcement action for $135 million in aggregate DOJ and SEC settlement amounts but disclosed approximately $550 million in pre-enforcement action professional fees and expenses (a 2.5:1 ratio compared to the settlement amount). Likewise, Bruker Corp. resolved an FCPA enforcement action for $2.2 million, but disclosed approximately $22 million in pre-enforcement action professional fees and expenses (a 10:1 ratio).[168]

Similarly, Hyperdynamics resolved an FCPA enforcement action for $75,000, but disclosed approximately $12.7 million in pre-enforcement action professional fees and expenses (a 170:1 ratio).[169] Perhaps most eye-popping, NATCO group resolved an FCPA enforcement action for $65,000, but disclosed approximately $11 million in pre-enforcement action professional fees and expenses (a 170:1 ratio).[170]

Even if the CEP was binding on the DOJ (which it is not), the fact is the policy only addresses bucket #2 (settlement amount) and does not address pre-enforcement action professional fees and expenses—the biggest financial hit to a business organization that is the subject of FCPA scrutiny.

On this issue, it is perhaps notable that the CEP falls short and is less explicit than the 2016 FCPA Pilot Program. On the issue of internal investigations, the prior Pilot Program stated:

[T]he Fraud Section does not expect a small company to conduct as expansive an investigation in as short a period of time as a Fortune 100 company. Nor do we generally expect a company to investigate matters unrelated in time or subject to the matter under investigation in order to qualify for full cooperation credit. An appropriately tailored investigation is what typically should be required to receive full cooperation credit; the company may, of course, for its own business reasons seek to conduct a broader investigation.

. . . .

For instance, absent facts to suggest a more widespread problem, evidence of criminality in one country, without more, would not lead to an expectation that an investigation would need to extend to other countries. By contrast, evidence that the corporate team engaged in criminal misconduct in overseeing one country also oversaw other countries would normally trigger the need for a broader investigation. In order to provide clarity as to the scope of an appropriately tailored investigation, the business organization (whether through internal or outside counsel, or both) is encouraged to consult with Fraud Section attorneys.”[171]

This language followed then Assistant Attorney General Caldwell’s April 2015 statement that the DOJ “do[es] not expect companies to aimlessly boil the ocean” in FCPA investigations.[172] The mention of the scope and breath of FCPA internal investigation in the 2016 Pilot Program was welcomed by the corporate community and the absence of this issue in the CEP is notable.

Yet another reason why the corporate community should take the CEP with a grain of salt is that it does not address the many other “ripple effects” of FCPA scrutiny and enforcement.

A company (particularly an issuer) subject to FCPA scrutiny and enforcement will often also experience several other negative financial consequences above and beyond the “three buckets” of financial exposure highlighted above.[173] Such financial consequences can include a drop in market capitalization, an increase in the cost of capital, a negative impact on merger and acquisition activity, lost or delayed business opportunities, and shareholder litigation.[174] In certain cases, these other negative financial consequences can far exceed even the “three buckets” of financial exposure.[175]

Moreover, FCPA scrutiny and enforcement actions are increasingly spawning related foreign law enforcement investigations and enforcement actions. Indeed, as the DOJ is fond of saying, “an international approach is being taken to combat an international criminal problem. We are sharing leads with our international law enforcement counterparts, and they are sharing them with us.”[176]

In short, corporate leaders need to fully understand and appreciate (in addition to the specific issues discussed above) that a voluntary disclosure of potential FCPA violations is going to set into motion a wide-ranging sequence of events that will be far more costly to the company than any marginal settlement amount benefit obtained through the CEP.

The deep gorge in the FCPA enforcement landscape visually depicted earlier in this section is a concerning policy issue and it is a laudable goal of the CEP (as well as the prior Pilot Program) to encourage voluntary disclosure in order to enhance the DOJ’s “ability to identify and punish culpable individuals.”[177]

However, there is an even better alternative than the CEP to bridge this gap. In this regard, it is notable that the CEP, which is after all based on the 2016 Pilot Program, is widely viewed as the brainchild of Andrew Weissmann (whose signature appears on the Pilot Program).[178] Prior to Weissmann becoming Chief of the DOJ’s Fraud Section in January 2015, he was a vocal critic of various aspects of the DOJ’s FCPA enforcement program as well as corporate criminal liability principles generally.[179] Among other things, Weissmann advocated for an FCPA compliance defense and stated:

The FCPA should incentivize the company to establish compliance systems that will actively discourage and detect bribery, but should also permit companies that maintain such effective systems to avail themselves of an affirmative defense to charges of FCPA violations. This is so because in such countries even if companies have strong compliance systems in place, a third-party vendor or errant employee may be tempted to engage in acts that violate the business’s explicit anti-bribery policies. It is unfair to hold a business criminally liable for behavior that was neither sanctioned by or known to the business.[180]

According to Weissmann, an FCPA compliance defense as well as other FCPA reforms he advocated were “best suited for Congressional action.”[181] In other words, Weissmann did not believe that changes to DOJ policy (which is all that the CEP and before that the Pilot Program represent) were enough. Moreover, when the DOJ announced in Fall 2015 the appointment of a compliance counsel to assist DOJ prosecutors in evaluating corporate compliance programs at the time of improper conduct to determine if fine reductions were warranted,[182] Weissmann (widely viewed as the architect of this position as well)[183] stated that a motivation in creating the position was to “empower a robust compliance function within organizations.”[184] Asked what he “hope[d] to accomplish in general and specifically to assist the compliance professional,” Weissmann responded: “I hope that, in seeing how seriously the Department of Justice takes compliance, we will strengthen the voice of the compliance professionals and help them get a stronger seat at the table as a key stakeholder in how businesses are run.”[185]

Whether it’s the CEP’s goal to, in the words of Deputy Attorney General Rosenstein, “motivate[] and reward[] companies that want to do the right thing and voluntarily disclose misconduct,”[186] the prior Pilot Program’s goal of “encourage[ing] companies to implement strong anti-corruption compliance programs to prevent and detect FCPA violations,”[187] or simply to best “empower a robust compliance function within organizations” and best “strengthen the voice of the compliance professional[] [to] help them get a strong seat at the table.,”[188] there are better alternatives to accomplish these laudable goals.

Like several former high-ranking DOJ officials and others, this author has long argued that an FCPA compliance defense (an actual statutory amendment, not merely a change in non-binding DOJ internal policy that grants the DOJ a wide amount of discretion) can best allow the FCPA enforcement agencies to accomplish their stated objectives.[189] My 2012 Article “Revisiting a Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Compliance Defense” I stated:

An FCPA compliance defense will better facilitate the DOJ’s prosecution of culpable individuals and advance the objectives of its FCPA enforcement program. At present, business organizations that learn through internal reporting mechanisms of rogue employee conduct implicating the FCPA are often hesitant to report such conduct to the enforcement authorities. In such situations, business organizations are rightfully diffident to submit to the DOJ’s opaque, inconsistent, and unpredictable decision-making process and are rightfully concerned that its pre-existing FCPA compliance policies and procedures and its good-faith compliance efforts will not be properly recognized. The end result is that the DOJ often does not become aware of individuals who make improper payments in violation of the FCPA and the individuals are thus not held legally accountable for their actions. An FCPA compliance defense surely will not cause every business organization that learns of rogue employee conduct to disclose such conduct to the enforcement agencies. However, it is reasonable to conclude that an FCPA compliance defense will cause more organizations with robust FCPA compliance policies and procedures to disclose rogue employee conduct to the enforcement agencies. Thus, an FCPA compliance defense can better facilitate DOJ prosecution of culpable individuals and increase the deterrent effect of FCPA enforcement actions.[190]

This was written before the 2016 Pilot Program and obviously before the CEP, but the logic still remains sound. Another policy objective that a compliance defense can achieve better than the CEP is increasing “soft enforcement” of the FCPA. In other words, a compliance defense can best incentivize business organizations to implement more robust FCPA policies and procedures and more robust policies and procedures can reduce instances of improper conduct and thereby advance the FCPA’s objectives. Critics of an FCPA compliance defense have ignored its potential “soft enforcement” impact focusing instead on “hard enforcement” issues such as the possibility that the defense would prove to be unworkable in a contested proceeding or lack practical value given that business organizations tend not to put the FCPA enforcement agencies to their burdens of proof.[191]

Such criticisms of a compliance defense miss the point entirely. In passing the FCPA, Congress anticipated that the “criminalization of foreign corporate bribery will to a significant extent act as a self-enforcing preventative mechanism.”[192] Likewise, since the FCPA’s earliest days, the DOJ has recognized that the “most efficient means of implementing the FCPA is voluntary compliance by the American business community.”[193] Indeed, Weissmann himself previously stated that FCPA reform should best motivate compliance “on a daily basis” and “regardless of what the DOJ is doing.”[194]

This is precisely what a compliance defense can better accomplish than the CEP. To best conceptualize this issue, consider three scenarios: