School District Secession in Mobile County, Alabama: A Case Study of Adaptive Discrimination and Threats to Multiracial Democracy

By

By

Sarah Asson[1]* & Erica Frankenberg[2]**

White families’ resistance to school desegregation in Mobile County, Alabama, has existed since Brown v. Board of Education and has adapted since the era of court-ordered desegregation. That resistance remains present to this day. Mobile County Public School System (MCPSS), once a countywide school district, was under court order from the time Birdie Mae Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County was filed in 1963 until the district was declared unitary in 1997. Beginning in 1963, when one MCPSS school was among the first in the state to be desegregated, there was staunch resistance to school desegregation by both White families and school leaders—largely permitted by the district court judges overseeing the case—which persisted through the duration of the case. Levels of racial and economic segregation in the county’s schools remained high even as the district was released from court oversight, as the district court judge responded to changing federal jurisprudence. Within the post-unitary context, school district secession has emerged in Mobile County as a new, seemingly race-neutral but essentially race-evasive mechanism to maintain segregation. Since 2006, three municipalities within the county have formed their own independent school systems. Though stakeholders relied on largely race-evasive language to argue in favor of secession, their arguments mirror those arguments historically used to resist court-ordered desegregation, and the effects of the splits are clearly racialized and perpetuate patterns of segregation. The maintenance of segregation over the past several decades undermines goals of integration and social cohesion necessary for a functioning multiracial democracy.

Once home to a countywide school district, Mobile County, Alabama, has had three municipalities break away from the district and form their own school systems in the past fifteen years.[3] School district secession, a process by which a community splits from a larger school district to establish its own independent system, has become increasingly common in the United States. There have been seventy-three successful successions across the country between 2000 and 2019,[4] and many are concentrated in the South.[5] Within Mobile County, three municipalities seceded in the span of five years: the city of Saraland established a separate school district in 2008 while neighboring Chickasaw and Satsuma each opened the doors to their separate districts in 2012. The case of Mobile County demonstrates a concerning trend in which school district secession proves to be a legally and politically sanctioned approach to maintaining segregation and inequality in an era of perceived race-neutral law and policy. As a form of adaptive discrimination,[6] secession threatens the potential of schools to foster a cohesive, multiracial democratic society.

The context of secession in the South cannot be disentangled from the region’s history of large countywide school districts and de jure segregation. Unlike the highly fragmented school districts of the Northeast or Midwest, those in the South have historically spanned entire counties, drawing students from both urban centers and rural areas. This feature of southern districts was particularly useful during the desegregation efforts following Brown v. Board of Education, and for a period, southern schools were some of the most integrated in the country[7] in part because of this jurisdictional feature of countywide districts.[8] More recently, however, many of the arguments used decades ago by White residents across the South to resist school desegregation have resurfaced in modern day school district secession attempts.

In Mobile County, the Birdie Mae Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County[9] desegregation case was filed in 1963 and remained active until unitary status was granted in 1997. Persistent throughout this period was staunch resistance to school desegregation by both White families and school leaders—largely permitted by the district court judges overseeing the case. Levels of racial and economic segregation in the county’s schools remained high even as the district was released from court oversight. Within this context, secession has emerged in Mobile County, as it has in other Southern school districts,[10] as a new race-evasive mechanism to maintain segregation that remains legally and politically acceptable in the twenty-first century. Indeed, within five years after unitary status was granted—which removed the requirement that a proposed secession be evaluated by courts as to desegregation impact—municipalities in Mobile County began to investigate how to secede from the county district. This Article analyzes how the arguments used throughout the processes of secession are linked to the historical arguments used during formal desegregation, and how the outcomes of secession serve to maintain segregation and inequality within the county’s schools. The case of Mobile County speaks to how the current political and legal context permitting district secession has serious implications for public schools and for democracy.

As explained by James Madison in the Federalist Papers, one of the fundamental goals of the United States’ democratic republic is to protect minority rights in a diverse society,[11] and public schools play a critical role in serving that goal.[12] Philosophers from Aristotle to John Dewey to Martha Nussbaum have theorized that “diverse education is consistent with democratic ideals.”[13] United States law has also supported such philosophical traditions; in finding segregated schools to be inherently unequal in Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court acknowledged “the importance of education to our democratic society”[14] and the threats of segregated schools to that society.

The Brown decision was based in part on social science research identifying the psychological harms of segregation.[15] Perhaps most well-known is Mamie and Kenneth Clark’s research showing that segregation is linked to low self-esteem and feelings of inferiority among young Black children. In a series of experiments, Black children as young as three displayed clear preferences for white dolls over brown ones.[16] Similarly, White children’s perceptions of self and others are also negatively shaped by segregated spaces,[17] a fact that went unrecognized by the Court in its Brown opinion.[18] Evidence presented as part of the Brown case found that racial segregation causes White children to “develop patterns of guilt feelings, rationalizations and other mechanisms which they must use in an attempt to protect themselves from recognizing the essential injustice of their unrealistic fears and hatreds of minority groups.”[19] Though some have critiqued such evidence,[20] updated research confirms the attitudinal and social harms of segregation on White children.[21]

Brown and subsequent Supreme Court decisions have led to some level of school integration across the United States.[22] Research has found that children who attend racially integrated schools benefit from more cross-racial friendships[23] and a lower propensity for prejudice and stereotypes[24] than those who attend segregated ones, supporting the theory of intergroup contact.[25] Research also shows that students who attend integrated schools report more opportunities to learn civic and political skills[26] and have higher rates of civic engagement later in life.[27] In the long-term, students who attend integrated schools are also more likely to live and work in integrated spaces as adults.[28] Contact with those from diverse backgrounds, particularly when structured appropriately, also generates critical thinking and problem-solving skills that not only academically benefit students in schools but also extend to the workplace. Several social science experiments reveal that diverse teams perform better on group tasks and come up with more creative solutions than homogenous groups.[29] The ability to work and live within diverse teams and neighborhoods is increasingly necessary in our multiracial, yet divided, society.

Though the evidence in support of desegregation is strong, the nation’s public schools today remain highly segregated,[30] threatening some of our most valued democratic ideals and educational goals. Rather than embrace the heterogeneity celebrated in the Federalist Papers, segregated school systems allow people to avoid having to compromise over different views and commit to a multiracial democracy. Furthermore, rather than serve the educational goal of democratic equality for all students, segregated schools tend to serve more individualistic goals of social mobility for advantaged students.[31] In all, centuries of philosophy and decades of scientific evidence support the claim that school segregation threatens students’ futures as citizens in a multiracial democracy.

In the United States, school district boundary lines play a crucial role in shaping students’ access to education.[32] Boundaries serve many purposes, including defining the geographic area of a school district, delineating which students will attend the district, determining a certain pool of available resources, and signalling an area’s identity. Given these roles, the significance of boundary lines is clear.

As a shaper of identity, school district lines convey information about a school district. In particular, district boundaries convey racial information to families who are choosing where to live and where to enroll their children.[33] For example, Jennifer Jellison Holme found that White and wealthy parents choose to move to school districts with higher proportions of White families rather than making decisions based on objective measures of school quality.[34] Similarly, Allison Roda & Amy Stuart Wells found that parents concerned with sending their children to the “best” schools ultimately chose racially isolated, mostly White schools, which suggests that perceived quality is commonly conflated with race.[35] In general, research shows school districts can develop “good” or “bad” reputations that are closely associated with the demographic characteristics of the districts’ students.[36]

Additionally, school district lines determine a pool of available resources upon which schools can draw. Most school district revenue comes from local sources like property taxes, so the value of homes within a district can determine the amount of funds and resources available to an area’s school. Obviously then, districts with more expensive homes collect more tax dollars to support their schools, advantaging those already economically privileged children with better school resources.[37] Because property values tend to be higher in districts with more White students relative to surrounding areas, district boundaries also help correlate school funding levels with an area’s racial demographics.[38]

Finally, in defining the geographic scope of a district, boundary lines enforce a concept of local control— a hallmark of American education—in which those within a district determine much of the policy. Public support for local control is high among Americans of all races,[39] as people believe that those closest to the community will be able to make the most appropriate decisions given the local context. However, calls for local control have historically conflicted with calls for increased equality, notably during the period following Brown v. Board of Education when districts used local control to thwart efforts to desegregate.[40]

Given their ability to shape identity, organize resources, sort students, and define geographic areas of control, school district boundaries have important implications for patterns of school segregation.[41] In a 1972 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court prohibited the formation of a district that wished to break away from a larger district under desegregation obligations because the action would impede the effectiveness of desegregation efforts.[42] However, a few years later, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Milliken v. Bradley solidified the importance of school district boundary lines in perpetuating segregation.[43] The Court held that the federal government could not mandate desegregation across district lines, leaving suburban districts free to close themselves off from urban districts and avoid responsibility for any resulting racial segregation.[44] Thus, White flight to homogenous suburban school districts helped thwart efforts to racially integrate America’s schools.[45] Today, the majority of school segregation is due to separation between school districts rather than within school districts,[46] and such segregation has harmful student and community outcomes.[47]

School district secession further perpetuates the segregative effect of school district boundary lines. Across the country, high levels of district fragmentation are correlated with segregation.[48] Of particular concern is the ways in which school district secession efforts are often removed from conversations of intentional segregation. “[S]ecessions are grounded in the race-neutral language of localism, or the preference for decentralized governance structures.”[49] And yet, recent research has directly linked the act of secession to increasing levels of segregation between school districts, especially in the South.[50] Furthermore, inequitable school funding results when wealthy areas secede from higher poverty districts.[51] Secession appears to be one of the latest methods for maintaining patterns of segregation, drawing on the power of school district boundaries to do its segregative work.

Throughout the United States’ history, educational boundaries have been used in various ways to maintain systems of school segregation. The evolution of such strategies can be explained by Elise Boddie’s concept of adaptive discrimination.[52] Before Brown v. Board of Education, formal student assignment policies maintained de jure segregated schools. During the era of court-ordered desegregation, however, courts required individual school districts to redraw their school attendance zones to create racially balanced schools. The use of race-conscious school boundaries was endorsed by the Supreme Court in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,[53] and since then, court-ordered and voluntary desegregation plans alike have relied on redistricting as a desegregation tool.[54] However, as court-ordered desegregation began to take hold across the country, there was massive resistance to integration efforts, and White families fled to suburban school districts to avoid integrating urban schools.[55] In effect, because school boundary lines were no longer sufficient to separate students, White families came to rely on more robust district lines to maintain separation.

Attempts by the courts to intervene and alter segregative district boundary lines were less successful than those altering school boundary lines. In 1970, the NAACP sued state officials in Michigan for practices they claimed led to stark segregation between the Detroit public schools and surrounding White suburban school districts.[56] The district court agreed and ordered the state to develop a desegregation plan that would encompass fifty-three school districts in the metropolitan area.[57] But on appeal, the Supreme Court ultimately held that federal courts could not require desegregation across district lines without evidence of intentional discrimination on the part of the suburban districts or the state when drawing district boundaries—a near impossible thing to prove.[58] In his dissent, Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote “school district lines, however innocently drawn, will surely be perceived as fences to separate the races,”[59] and his warning has proven all too true.[60]

Since the 1990s, the federal courts have largely retreated from enforcing school desegregation.[61] Supreme Court decisions in Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell,[62] Freeman v. Pitts,[63] and Missouri v. Jenkins[64] essentially allowed courts to end desegregation oversight before school districts had fully complied with remedial court orders, so long as school districts had complied in “good faith” and segregation had been remedied to the “extent practicable.”[65] The Freeman v. Pitts decision, in particular, emphasized a shift in the Court’s thinking towards viewing residential segregation patterns as private decisions[66] rather than as responses to government policies, although it had previously recognized this reality.[67] These shifts led to the premature release of many school districts from court oversight and a subsequent resegregation of the country’s schools.[68] The Court does still accept the use of school boundary rezoning for desegregation; most recently, Justice Kennedy’s concurring opinion in Parents Involved v. Seattle School District No. 1 endorsed the voluntary use of race-conscious districting plans as a mechanism for creating racially balanced schools.[69] But today, the federal courts remain largely uninvolved in decisions surrounding local educational boundaries, and there exist many places where district and school boundaries reinforce or worsen segregation.[70]

Contemporary school segregation is especially visible in the separation of White students from non-White students, both between schools and school districts. Legal scholar Erika Wilson describes this clustering of White students—and their associated power, funds, and social capital—as “monopolizing whiteness.”[71] She explains that while traditional segregation scholarship focuses on the harms of segregation for students of color, there is limited discussion of “the meaning and consequences of racial segregation in schools for [W]hite students.”[72] She also argues that school segregation could be addressed through alternate frameworks such as an antitrust framework, given the resource hoarding linked to White segregation.[73]

Because educational boundaries convey both information about an area’s reputation and the effects on distribution of educational resources, people are incentivized to maintain exclusionary lines. For decades there has been a rise in enclaves, or areas that are Whiter or more affluent than surrounding areas.[74] People in enclaves have more resources than those in surrounding areas, and they work to close off those resources to maintain opportunities for themselves in a process of social closure.[75] In this way too, boundaries can play a causal role in shaping the populations living within a district by attracting those who can afford access and excluding those who cannot.[76] The rise in segregated White enclaves also demonstrates the shift over the past several decades towards conceptualizing publicly-funded schools not as a public good but instead as a private one meant to prepare one’s child(ren) to compete for social and economic positions. Rhetoric about wanting the best for one’s own child, to the detriment of others, helps to rationalize segregation, especially within a society that claims colorblindness and race-neutrality.

In many areas of contemporary society, people use “facially race-neutral laws and practices” to “continuously reproduce and entrench racial disadvantage across our social landscapes.”[77] Such practices may rely on previous iterations of racially discriminatory laws, all while claiming race no longer plays any role. For example, decades of government policies created and then maintained the residential segregation and massive racial wealth gaps that exist today.[78] School district boundaries are overlaid on such patterns, creating segregated and unequal schools. But rather than require policy solutions to address racial school segregation, laws increasingly mandate that student assignment policies not include race as a consideration.[79] Such rulings have been critiqued by scholars arguing that colorblind policies can maintain inequality and constitute a new form of racism.[80]

School district secession represents one clear example of a “facially race-neutral” practice that in fact has racialized implications and undermines democratic ideals. State laws allowing for district secession do not explicitly involve race, and stakeholders involved in secession attempts use race-evasive language to describe their goals.[81] For example, in Shelby County, Tennessee, researchers documented the use of the “local control” argument to justify a series of district secessions in 2014; court challenges to secessions there did not succeed.[82] Another common argument in favor of secession calls to keep educational resources close to home. For example, while pushing for an ultimately unsuccessful secession in Gardendale, Alabama, the mayor of the city stated that the proposal was about “keeping our tax dollars here with our kids, rather than sharing them with kids all over Jefferson County.”[83] Though these rationales do not explicitly mention race, they can implicitly create racial discrimination because secession, by definition, works to separate groups. As political scientist Gregory Weiher argued, the formation of new political boundaries such as municipalities or school districts is essentially an anti-democratic move meant to “shield” homogenous groups from others.[84] And yet, secession remains politically acceptable to many residents and legally permissible in most states across the country.

Mobile County is the second most populous county in Alabama and one of two coastal counties that span Mobile Bay.[85] It is home of the state’s largest and oldest school district, Mobile County Public School System (MCPSS).[86] The county is a sprawling 1,644 square miles and has grown by nearly 100,000 residents since 1960.[87] It has remained a majority White county, with Black residents historically being the largest non-White group. The Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County was created in 1826, predating even the state department of education.[88] Throughout the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth century, MCPSS, like most southern school districts, operated a dual system of segregated schools, as reinforced by Alabama state law that called for the assignment of students to schools based on race.[89]

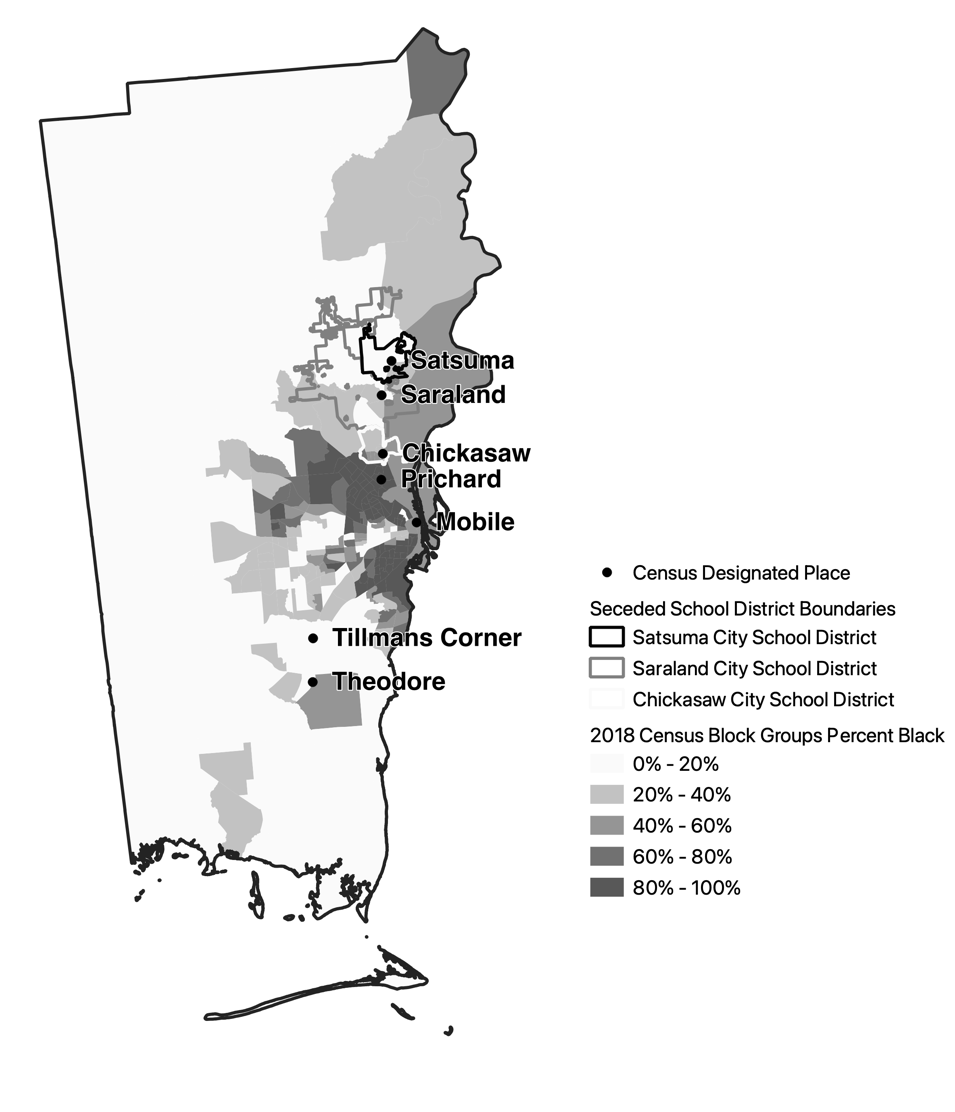

Three cities within Mobile County have formed independent school districts and are the focus of this Article: Saraland, Satsuma, and Chickasaw (See Figure 1). Because MCPSS was originally a countywide school system, town limits were not necessarily coterminous with school attendance zones, and residents of these three separate towns were linked through their shared and neighboring schools.

Figure 1: Mobile County Seceded School Districts and Census Designated Places, 2018[90]

Saraland is a community in the northeast portion of Mobile County that incorporated in 1957 with only 125 residents.[91] It began to grow in the 1960s as an industrial and population boom occurred in the city of Mobile. Saraland contained two MCPSS schools, Saraland Elementary School and Nelson Adams Middle School.[92] Before integration, and during most of the desegregation case, most Saraland students attended Satsuma High School in the next town over.[93] Satsuma, named after the Mandarin Satsuma oranges brought to Alabama from Japan in the late 1880s, submitted plans for a town charter in 1959.[94] During the era of desegregation, it contained Robert E. Lee Elementary School (later split into a primary and intermediate school), named for the Confederate general. Most Satsuma students then attended Nelson Adams Middle School in Saraland before attending Satsuma High School.[95] Both Satsuma and Saraland grew rapidly in the latter half of the twentieth century, each doubling in size between 1960 and 1980 and steadily increasing since 1980 (See Table 1). The cities both have overwhelmingly White populations.

Just to the southeast of Saraland sits Chickasaw, a small community named after the Native American tribe. Chickasaw was incorporated in 1946, after experiencing growth during World War II as the shipbuilding industry moved in.[96] Chickasaw’s population declined in size after the middle of the twentieth century, and particularly after 2000, the town experienced a sharp decline in the percentage of White residents.[97] The town had two elementary schools and one middle school: Chickasaw Elementary School, Hamilton Elementary School, and Clark Middle School. Students then went to the nearby town of Prichard to attend Vigor High School.

| Table 1: Mobile County Census Designated Places with More than 5000 Residents in 2020[98]ψ | ||||||||||

| 1960 | 1980 | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | ||||||

| population | % white | population | % white | population | % white | population | % white | population | % white | |

| Chickasaw | 10,002 | 100 | 7,402 | 99.2 | 6,364 | 88.9 | 6,106 | 63.0 | 6,457 | 48.8 |

| Mobile City | 202,779 | 67.5 | 200,452 | 62.8 | 198,915 | 50.4 | 190,511 | 44.9 | 187,041 | 40.1 |

| Prichard | 47,371 | 52.8 | 39,541 | 25.8 | 28,659 | 14.2 | 22,659 | 12.5 | 19,322 | 11.6 |

| Saraland | 4,595 | 90.3 | 9,833 | 95.4 | 12,288 | 88.5 | 13,405 | 83.7 | 16,171 | 76.5 |

| Satsuma | 1,491 | | 3,822 | 92.9 | 5,687 | 93.7 | 6,168 | 88.7 | 6,749 | 84.9 |

| Theodore | | | 6,392 | 72.5 | 6,811 | 71.1 | 6,130 | 79.8 | 6,270 | 66.8 |

| Tillmans Corner | | | 15,941 | 98.9 | 15,685 | 93.6 | 17,398 | 82.2 | 17,731 | 67.5 |

| COUNTY | 314,301 | 67.7 | 364,980 | 67.6 | 399,843 | 63.1 | 412,992 | 60.2 | 414,809 | 54.7 |

Prichard is also central to this story. This settlement, located just south of Chickasaw and north of the city of Mobile, grew steadily throughout the 1900s, as the shipbuilding and paper mill industries moved in along the area’s waterfront. Prichard was incorporated in 1925 and became a company town for shipbuilders during World War II.[99] Throughout this time period, it had a growing population and thriving business district. However, in the 1960s, Prichard began to lose middle class and White residents to newly developing suburbs, including those forming to the west. The 1980s and 90s saw the closing of factories in Prichard, leading to rising poverty, unemployment, and crime,[100] and in 1999, the municipality declared bankruptcy.[101] The contrast between Prichard’s decline and the growth of neighboring cities set the stage for some of the secessionist talks that began in Mobile County during the era of court-ordered desegregation.

Despite the efforts of local civil rights activists, school desegregation did not come to Mobile County following the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling. Rather, it was stalled until Birdie Mae Davis v. Board of Commissioners, Mobile County was filed in 1963 by local Black parents on behalf of their children.[102] In September 1963, two Black children in Mobile integrated a formerly all-White high school, joining a handful of Black students in other parts of Alabama to finally integrate K-12 public schools in the state. Desegregation efforts across Mobile County were slow and featured strong resistance of White parents and school leaders alike.[103] We present a brief overview of court-ordered desegregation in Mobile, focusing particularly on the areas of the county that later experienced secession. Those areas include the three towns that seceded—Saraland, Satsuma, and Chickasaw—as well as the neighboring communities.

Early years of desegregation in Mobile County saw very slow progress. From 1963 to 1968, the district used a freedom of choice plan to allow parents to choose the schools their children would attend, but this did not generate any widespread desegregation.[104] While a few hundred of the district’s more than 30,000 Black students enrolled in previously all-White schools, virtually no White students chose to attend all-Black schools. Overall, most students remained in their segregated neighborhood schools.[105]

Given the lack of progress and the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the United States Department of Justice entered the case in 1967 as a plaintiff intervenor. For the next three years, the school board and many White parents strongly opposed the federal government’s plans of rezoning students to schools outside of their neighborhood. White parents organized a group called Stand Together and Never Divide (STAND) to oppose desegregation, decrying the role of the federal government in forcing desegregation and the perceived end of local control over their schools. The case was frequently the subject of legal appeals as the district court judge typically approved only modest changes to desegregation efforts. When a new desegregation plan was approved in 1970, some White students ignored their new school assignments outright and attended a school other than the one to which they had been assigned as “non-conformers” who suffered no consequences.[106] The case ended up in the Supreme Court in 1971 and was decided as a companion case to the Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg case, ultimately requiring the desegregation efforts in Mobile to extend westward beyond the interstate and include more majority White areas.[107] A consent order governing the case was reached in July 1971, and lasted for three years. But by 1971, private school enrollment in Mobile County peaked at almost 18,000 students, as many White families fled public schools to attend segregation academies.[108]

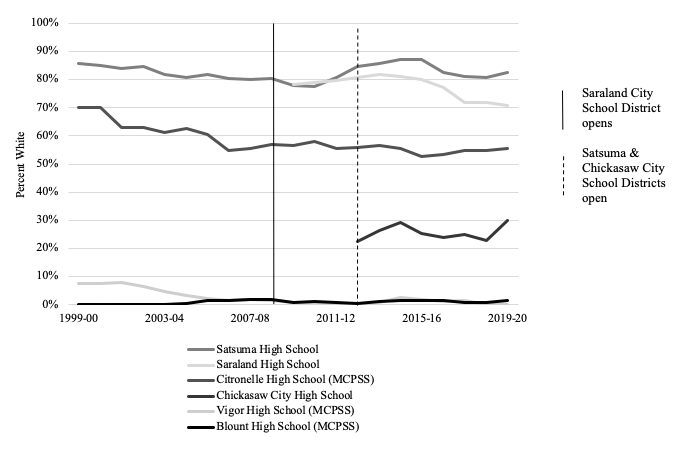

The district enrollment remained majority White despite the flight—53% White in 1972, and remained relatively stable over the next quarter-century.[109] Although this should have made desegregation numerically feasible, segregation persisted in many MCPSS schools throughout the 1970s due to staunch resistance by Whites within the county. In 1974, the district still effectively maintained a dual school system, in which the rural schools were 81% White and the urban metro schools were 59% Black.[110] By 1976, thirty-two of the district’s eighty schools were still racially identifiable, or had student populations in which 85% were of a single race.[111] During this time, the local newspaper, the Mobile Register, opined that school desegregation was a “failure,” an experiment in “social engineering,” and “obnoxious,” reflecting widespread views held by White Mobilians that desegregation was a burden.[112] In fact, throughout this time period the Register espoused a narrative that hampered desegregation efforts,[113] encouraging the White resistance to desegregation and White flight from the public schools, both of which served to preserve a state of racial isolation. The city of Prichard, for example, saw demographic shifts as White students fled its schools. Vigor had been the White high school in Prichard before desegregation,[114] but as Whites resisted desegregation—including by enrolling in parochial schools—Vigor became 67% Black by 1980.[115] Nearby Blount High School was the traditionally Black high school in Prichard, and it remains 98% Black as of 2019.[116]

Meanwhile, some Black parents also came to oppose the desegregation efforts, as they almost exclusively bore the burden of integrating schools.[117] Black citizens resented desegregation policies that closed their neighborhood schools and reassigned Black students to schools miles away from home, where they may not have been welcomed. Over the years, some Black residents in Mobile also talked of splitting away from MCPSS to create their own school district, fearing violence and the loss of their school traditions during integration.[118] Prichard officials in particular mentioned possible secession efforts,[119] following the separatism movement championed by Roy Innis of the Congress of Racial Equality.[120] Black residents’ desire to break away was motivated by the way in which the adopted desegregation remedies overwhelmingly favored White families. Had any split happened, of course, it would have gone against the modern trend of predominantly White areas seceding. But not every Black citizen supported separatism, and the integration efforts pursued by the NAACP and the Birdie Mae plaintiffs continued.

In the 1970s, there was also a separate court case that challenged school board commissioner elections in MCPSS. At the time, at-large elections meant all constituents within Mobile voted on all school board candidates, and given the White majority within the country, the school board remained all White. The Brown v. Moore case, however, argued that the system diluted Black voting strength as Black constituents were a minority, albeit substantial in size, in the county.[121] The plaintiffs won the case, and MCPSS adopted district elections, whereby the county was carved into five voting districts, each one voting on its own school board member.[122] This led to the first Black school board members being elected in 1978, ensuring Black families would have direct representation on the school board.[123]

In 1981, a new consent decree “established two community committees to help resolve the Birdie Mae Davis case.”[124] Of continued debate were school rezonings and busing, as well as specific issues that would portend later secessions. Several groups of White parents protested plans to rezone their students to far away schools. In their protests, many parents echoed a sentiment expressed by one Pat Leffingwell who stated, “our argument is not racially motivated. We are concerned about the distance, time and expense of busing our children.”[125] Others decried the loss of their freedom or their local control, asking, “Where has our freedom gone? . . . This is a dictatorship when one tells your child he has to go to a certain school.”[126] Despite their claims, much of this language stemmed from racially motivated resistance to desegregation and completely overlooked the fact that Black families had been experiencing school closures, rezonings, and long bus rides for decades, much less the denial of their constitutional rights prior to Brown. This language also foreshadowed the arguments later used by Whites in favor of secession.

In fact, some of this discussion began to emerge in the 1980s. Alabama State Representative Taylor Harper first proposed a bill in the State Legislature in 1982 that would have required a popular referendum vote on the splitting of MCPSS into two districts: one for the city and one for the surrounding county.[127] Support of this idea mostly came from the county residents who felt that schools within the city of Mobile received more attention and that their children were being ignored by the board of commissioners.[128] Though this bill never passed, it set the stage for the secessions that later took place, as it highlighted a divide between county residents, who were largely White, and the higher shares of Black residents living in and around the City of Mobile.

The desegregation case still lingered without resolution to persisting segregation, and in the 1980s, there were several specific debates related to the areas of Saraland, Satsuma, and Chickasaw. For example, in 1986, the school board submitted a rezoning plan to the court that was rejected, in part, because it called for Black students attending Vigor High School in Prichard to be bused to the relatively new and predominantly White Satsuma High School, but it did not reassign White students at Satsuma High School to Vigor.[129] When the board revised its plan to include this exchange, White parents resisted.[130] In fact, the municipality of Saraland, which sits between Satsuma and Prichard and was zoned to Satsuma High School, adopted a formal resolution against the plan.[131] Blount High School in Prichard was another centerpiece of debate, as it remained all-Black and was desperately in need of facilities updates. One of the community committees in the early 1980s suggested building a new Blount High School in Eight Mile, an area in north Mobile adjacent to Prichard that would more naturally draw a diverse enrollment.[132] However, Blount High School families strongly opposed this. They did not want their neighborhood school to be closed and moved, causing their children to take long bus rides as had been happening since 1970 in Mobile. This idea was eventually discarded for the time being, though it would later resurface.

In the late 1980s, a new plan for desegregation emerged that relied heavily on the use of magnet schools as a voluntary integration method—a compromise to the repeated use of mandatory rezoning as a desegregation tool. The Mobile Plan, as it came to be known, was approved by the court in June 1988. It called for the creation of six magnet schools that would be opened over the following three years: Council Elementary School, Phillips Middle School, Old Shell Road Elementary School, Dunbar Middle School, Chickasaw Elementary School, and Clark Middle School.[133] The creation of magnet programs in these schools meant that most students previously zoned to these schools would have to be rezoned to other schools outside their neighborhoods, as magnets were choice options open to anyone within the district to attend. The rezoning of students, especially Chickasaw students who previously attended Chickasaw Elementary and Clark Middle School, would cause tension over the years. The plan also called for $22 million worth of construction, $1.3 million of which was to be devoted to capital improvements at the existing Blount High School.[134] In fact, the agreement stipulated that 60% of the total construction funds were to be devoted to majority Black schools or to magnet schools. The agreement also included some attendance zone changes that, for one, finalized the assignment of half of Satsuma’s students to Vigor High School.[135] While the plan received widespread support, it still fell short in many regards. For example, the mayor of Prichard denounced the plan for failing to provide for improved educational opportunities at Blount.[136] He wanted Blount to become a magnet school,[137] though his idea appears to never have been seriously considered.

The adoption of magnet schools proved to be a turning point for desegregation in Mobile in that it accelerated discussion towards the district’s unitary status. Demand for magnet schools was high, and by 1992, about 1,600 of the 3,000 students attending magnets were White.[138] This was the first time that any significant number of White students was choosing to attend integrated schools. However, explicit patterns of segregation remained in the county’s schools overall. In 1996, the local newspaper, the Press Register, brought attention to remaining inequalities, including disproportionate numbers of White students in academically advanced classes, disproportionate numbers of Black students receiving suspensions, uneven distribution of the least experienced teachers in majority Black schools, and racial gaps in standardized test scores.[139]

Throughout the county, opinions on the state of desegregation were quite mixed. Many school district leaders wanted the long-standing desegregation case to be dismissed, allowing MCPSS to be released from federal oversight after decades of court intervention. However, others—such as Black school board members—pointed to the continued state of inequalities in MCPSS schools and noted that unitary status would stall further progress. “In 1996[,] forty-three of the school system’s ninety-seven campuses had student populations that were racially identifiable” or had a population with more than 85% students of one race.[140] As momentum towards unitary status accelerated, some of the original plaintiffs and other citizens created a group called Friends of Birdie Mae in an attempt to oppose the closing of the case.[141] There were also efforts to try to require a super-majority for some of the five-member board’s votes in order to ensure Black board members had greater voice in district decision-making. Despite these efforts, on March 27, 1997, district judge William Brevard Hand dismissed the Birdie Mae Davis case. Even the vote by the school board to accept the court’s decision fell along racial lines. The three White school commissioners voted to approve the unitary status settlement, while the two Black commissioners voted against it.[142]

The end of the Birdie Mae case in Mobile County reflected larger shifts in the courts’ thinking regarding school desegregation. In its Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg ruling in 1971, the Supreme Court recognized the role that federal, state, and local governments played in creating segregated residential neighborhoods, and it acknowledged that additional school district policies around school siting and attendance zones “may well promote segregated residential patterns.”[143] But by the 1990s, the Court began to view patterns of residential—and by extension, school—segregation as a result of private citizen actions and therefore beyond the purview of courts and school districts. In the Freeman v. Pitts decision, the Supreme Court declared that “[w]here resegregation is a product not of state action but of private choices, it does not have constitutional implications.”[144] Federal courts thus took large steps back from enforcing school desegregation orders and prematurely released many districts from court oversight, signaling an era of increasingly race-evasive jurisprudence. The refusal to address “private,” yet segregative, decisions about where to live and send one’s child(ren) to school foreshadows the legal context that would later allow for successful secession movements in Mobile County.

Bolstering the unitary status decision was an enduring White resistance to desegregation that reinforced false narratives about the causes of persistent inequality. Rather than recognize vestiges of segregation as a driver of the inequality between White and Black residents, White Mobilians attributed it to the inferiority and laziness of Black people.[145] Additionally, White residents perceived a lack of overtly racist attitudes and actions as a sign that efforts to remedy racial inequality were no longer needed or were even unfair to White students.[146] This narrative demonstrates the political context that further encouraged the ensuing secessions and the race-evasive rationales behind those secessions.

Contemporary calls for secession began to formalize in 2002 when the areas of Saraland, Chickasaw, Satsuma, and Creola banded together to consider creating an independent school district.[147] This discussion was inspired by a couple events.

First, in a May 2001 referendum, taxpayers approved an increase in property and sales taxes across Mobile County to support the schools.[148] Multiple attempts had failed in previous years, and the last tax increase had not been since 1961—two years before the Birdie Mae Davis case was filed.[149] As of 1999, the district’s local funding was one-third less than the state average.[150] Mobile city residents had typically been in favor of increasing their taxes to support the schools, but referendums had routinely failed before as county residents rejected them. In 2001, the MCPSS superintendent insinuated that prior defeats of tax hikes were motivated by racism on the part of White county residents unwilling to support higher taxes, which they believed would fund inner-city schools with sizeable Black populations.[151] He also threatened the end of high school football, a sacrosanct Alabama tradition, if the current vote did not pass.[152] The 2001 referendum passed by a clear margin, with 56.3% of all voters approving it, but votes still fell along geographic and racial lines. County voters outside of Mobile and Prichard rejected the tax increase with 56% voting no, while voters from Mobile and Prichard passed it at 66%.[153]

News articles at the time attributed the talk of secession to concerns over money.[154] School facilities across the county were in a poor state in 2000, after years of a lack of spending and the failed referendums to increase taxes. While under court order, the school board was required to prove to the court how any school construction would impact desegregation.[155] Rather than face this burden, the district largely avoided spending money on any construction or maintenance in the 1960s and 70s.[156] Though the 1988 agreement did call for capital improvements, the requirement that 60% of this money be directed to majority Black schools may have also reinforced White residents’ determination to not increase taxes. White residents may have been convinced their tax dollars would not support schools closest to where they lived. Of course, this view reflects an anti-democratic conceptualization of schools as private goods to be funded only by those who directly use them, rather than as public goods that benefit the larger community. Moreover, if schools had been more integrated, there might have been less concern about which schools were receiving additional funds. Furthering the strain, MCPSS school board member Hazel Fournier threatened to withhold funding for school improvements in those areas considering secession, noting that it would be unwise to spend money on school buildings that the district may lose.[157] Residents reacted sharply to these remarks by their school board member, with the Saraland mayor calling Fournier’s comments “blackmail.”[158] In fact, there seemed to be palpable tension between the predominantly White residents of these communities and Fournier, the Black school board member who represented them.[159] Feelings that they were not being represented in the countywide system, concerns over a lack of investment in their schools, and an unwillingness to invest in other schools across the county motivated residents in these areas to explore secession.

Furthermore, in 2002, MCPSS began talking once more about rebuilding Blount High School in Eight Mile, and many families were concerned they would be rezoned to the new school. The district hoped that moving Blount out of Prichard and redrawing its attendance zone would help bring in rural White students to this all-Black school.[160] At the time, about half of Saraland students were zoned to Satsuma High School, which was 84% White, and half were zoned to Vigor High School, which was 8% White. Citizens at both schools worried about being rezoned to a new Blount building, which had zero White students at the time.[161]

Within this context, Saraland, the largest of the north Mobile municipalities, formed the Delta Schools Association with neighboring Chickasaw, Satsuma, and Creola residents to explore the possibility of seceding together. Saraland’s mayor visited other secession districts in Alabama in order to gain information about the feasibility and process of secession.[162] The Delta School Association also planned to hire a group to perform a feasibility study.[163] Ultimately, this secession did not go through, as state law had no provision for allowing multiple municipalities to form their own school district.[164] In fact, Alabama Code Section 16-13-199 states that any municipality with a population of at least 5,000 may choose to establish its own city board of education.[165] No vote by any citizens, in either the seceding area or the area left behind, is required. However, because the statute does not specify that multiple municipalities may establish a new school board together, this joint secession attempt would have required an act of the state legislature.[166] This joint attempt did not pan out, but thoughts of secession remained.

Saraland continued its own discussions of secession and ultimately began to speed up its decisions in 2006.[167] At the time, a bill was working through the Alabama legislature that would have made school district secession processes more difficult. The bill would have required a municipality to have 15,000 residents, rather than the current 5,000, before it could secede. At the time, Saraland had fewer than 13,000 residents. In addition, the bill would have required cities to prove their financial capability to support their own school district to the Alabama State Department of Education, and cities would not automatically receive county school buildings within their boundaries upon secession. The bill was passed by the Alabama State House Education budget committee in March 2006, and Saraland City Council members thus began their process to officially split from MCPSS so as to avoid any future complications if the bill became law.[168]

Discussions around Saraland’s possible split from MCPSS included several arguments, all carefully couched in race-evasive language. First, there was continued fear in 2006 that Saraland students would be rezoned to the new Blount High School building, which was finally being constructed in Eight Mile.[169] Notably, citizens were careful to clarify that their concerns here were not about the racial makeup of Blount High School, but about the far distance to the school.[170] And when a young Black Saraland resident voiced concerns at city council meetings about the racial motivations for and implications of forming a separate school district, Saraland mayor Ken Williams said, “This city’s wide open for Blacks to move here. I’m not a racist. Never have been, never will be.”[171] Of course, this exemplifies how race-evasive language and policy work; individuals do not have to be explicitly racist for their decisions to have racially discriminatory outcomes.[172]

Others, such as Saraland Councilman Howard Rubenstein, spoke of widespread desire for more local control.[173] Much of this desire for local authority stemmed from remaining money issues. Saraland citizens, forced to pay increased taxes for MCPSS schools since the 2001 referendum, expressed a desire for their money to fund the schools their children attended. According to Rubenstein, a couple hundred Saraland residents said they would have voted for the tax increase back in 2001 had the money gone directly to their local schools.[174] Some were also angry at the state of their school facilities and, specifically, the lack of renovations to Adams Middle School. In fact, MCPSS had been withholding funding for school improvements of Adams since 2002 when Saraland was threatening to break away for the first time, given Alabama law that MCPSS would relinquish the school if secession occurred.[175] But the lack of investment in the area’s schools only added fuel to the fire. And more than just a lack of facilities, there was a general sense that MCPSS schools were of poor academic quality, as some cited the fact that MCPSS’s schools were on probationary accreditation with the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools.[176] A news article at the time noted that Saraland residents “have for years felt slighted by the county school system. They say that both academic programs and building improvements have gone to other schools elsewhere in the county[] and that a disproportionality small amount of school system funding has been spent in the Saraland area.”[177]

Finally, there were notions of community pride. Councilman Rubenstein said of the possible split, “I feel this is going to increase local pride, school pride. Our residents will have a sense of ownership. They will be more comfortable supporting education.”[178] The mayor echoed these sentiments, saying, “I think we’ve got more pride here,” in contrast to the countywide school system.[179]

Together, the rhetoric around local control, school funding, and community identity forms a sort of political playbook for school district secession movements. These exact arguments, in addition to mirroring those used by Whites to resist desegregation in Mobile County during the Birdie Mae case, have appeared almost word for word in other communities around the country that have witnessed school district secession.[180]

When Saraland put a referendum on the school district split to vote in June 2006, voters approved it overwhelmingly.[181] Later that year, the Saraland City Council selected a school board for its new district, raised its sales tax to generate revenue for the district, and began preparations to build a new high school within the city. Formal negotiations on the split from MCPSS took several years, though. Most contentious were the discussions between Saraland and Mobile County officials about who would incur the debts on Saraland Elementary and Adams Middle School, which had recently undergone some repairs. Eventually, the Alabama Department of Education stepped in to mediate the final agreement, in which Saraland paid MCPSS $1.5 million for the school repairs.[182] In addition to the keys to these two school buildings, Saraland also acquired eighty acres of land from MCPSS. Saraland School Board Attorney Bob Campbell, who had been the school board attorney for MCPSS during the desegregation case, commented to the local paper, “I think we got 16, 17, maybe $22 million of property, and we didn’t pay for it.”[183] The agreement also stipulated that any student residing in Saraland could choose to stay in their current MCPSS school for up to four years.

In its first year of operation in 2008–09, the Saraland City School District served students in kindergarten through grade 9. The district placed its K-5 grade students in the existing Saraland Elementary School and its 6–9 grade students in the middle school, which it renamed the Saraland Middle School Adams Campus. It also began construction on a new $30 million high school.[184] In August 2009, 9th and 10th graders remained at the middle school in portable facilities while construction at the high school was finalized.[185] The high school opened its doors in January 2010 for 9th and 10th graders.

The split also led to confusion and frustration among families who lived outside the Saraland city limits but whose students had previously been zoned to Nelson Adams Middle School, including many students living in Satsuma. At first, it seemed that these students would be allowed to stay at Adams, even though they were not Saraland residents. However, in February 2008, six months before the new school system opened, the interim superintendent of Saraland City Schools announced that he did not have room for these students,[186] leaving MCPSS scrambling to find a place for them. The first plan was to bus the 500 displaced students to Shaw High School in west Mobile, but this option was met with opposition from parents.[187] Families’ resistance to being sent to Shaw, which was about twenty minutes away and had a 93% Black student population, led to a compromise in which displaced families were instead zoned to school in nearby Satsuma.[188] Beginning in the 2008–09 school year, displaced Adams families sent their 6–8 grade students to Robert E. Lee Intermediate School, which had previously hosted only 3–5 grade students. In the meantime, MCPSS began building a new $14.5 million middle school in Axis, north of Satsuma, to give those displaced students a permanent school.[189] This series of decisions, in part, fueled the secessions to come.

When MCPSS needed to build a new middle school in north Mobile, in part to house middle school students displaced by Saraland’s split from MCPSS, it deliberately placed the school outside of Satsuma city limits to prevent Satsuma from ever acquiring the building if it were to break away and form its own district as well.[190] The new school, North Mobile County Middle School, opened in name in 2008–09 operating out of the Robert E. Lee Intermediate School in Satsuma and then moved to its new building in Axis beginning in 2010.[191] Satsuma’s middle school students were zoned there, but this only furthered Satsuma’s desires to break away, as many residents did not like that their middle school was located so far away.[192]

The desire for their children to attend school closer to home was stated as a main driver of Satsuma’s split, but there were other arguments in favor of secession as well. Like Saraland, Satsuma residents talked of a local pride. Satsuma City Councilwoman Pat Hicks said, “We have a real strong community here. I’ll be honest with you, I think all people want local schools, neighborhood schools. I think you have more parent pride and parental involvement.”[193] Hicks also spoke of wanting to bring more residents and more jobs to Satsuma.[194] The area had seen some local paper mill industries close in 1999 and 2000 and experienced a corresponding loss of jobs.[195] Local residents believed their own school system would attract new businesses and new residents to the area. Satsuma Councilman Tom Williams said, “I feel that we can better educate our children than the Mobile County school system. Splitting off would be a benefit for people who are proposing to move to this area. It would make Satsuma a more attractive place to live.”[196] Again, like Saraland, the stated reasons for secession in Satsuma were not about race. They were about local control, community pride, and generating economic growth. However, it is hard to ignore the fact that in 2010, Satsuma’s population was 89% White, compared to 60% for the county as a whole and 45% for the city of Mobile.[197]

Given the strong community support in favor of secession, the Satsuma City Council voted in January 2011 to split from MCPSS.[198] And in April, 60% of Satsuma voters approved a 7.5 mill property tax to fund the new school district,[199] demonstrating an economic commitment to the decision.

In neighboring Chickasaw, certain arguments for secession closely mirrored those of Satsuma. For example, Chickasaw residents were also upset about their children having to attend schools outside of the city. The 1989 desegregation consent decree had converted two of Chickasaw’s schools to magnet schools, so nonmagnet students in Chickasaw were bused to Chastang Middle School in Mobile’s Trinity Gardens and to either Blount or Vigor High Schools in Prichard.[200] Paul Sousa, who would become the interim superintendent of Chickasaw City School District as it began,[201] said “Chickasaw political and civic leaders have long been frustrated by the fact that the county system closed two of the city’s schools decades ago to establish countywide magnets there.”[202] Chickasaw Mayor Byron Pittman shared this view, stating that residents do not like sending their children outside of the city limits to attend middle and high school.[203] Additionally, those Chickasaw residents who did attend the city’s Clark Magnet School were upset by MCPSS’ decision to move the STEM magnet to Shaw High School in northwest Mobile beginning in the 2009-10 school year. Local resident Teresa Colvin said, “When you have children in their community schools, parents have more involvement and there’s more community pride, which is what I’d like to see here,”[204]—a statement that echoed almost word for word the sentiments shared by Satsuma officials.

And like residents of Satsuma and Saraland, residents of Chickasaw, a city which had been experiencing decades of population decline, also believed their own school system would attract additional homebuyers and generate population growth. Chickasaw City Councilman Ross Naze spoke of the families he saw leaving Chickasaw and the desire to attract new families to come in, buy homes, and revive the city.[205] The decision to start a new school system was linked to larger efforts to reinvent Chickasaw as a whole and make it a bustling, strong community.[206]

However, there existed other, likely racially-motivated reasons for the split. Calls for secession became especially loud in 2010 when MCPSS temporarily moved the district’s alternative school, which was 73% Black, into the former Chickasaw School of Mathematics and Science building.[207] MCPSS promised to find a different, permanent location for the alternative school—comprised of students permanently suspended from other schools—within three years; in the interim, Chickasaw residents complained that the school’s students were “roaming around,” “being disruptive,” and making the neighborhood not as “attractive.”[208]

Inherent in this effort, too, was a general anti-Prichard sentiment in Chickasaw. For most of its history, Chickasaw was an overwhelmingly White community, remaining almost 90% White in 2000. When Black residents did begin to move into the Chickasaw area, the demographics of the community changed quickly, becoming 63% White and 34% Black by 2010. In 2010, Prichard was 88% Black with a median household income of $21,583 and a median home value of $65,900. The relatively more affluent area of Chickasaw, with a median household income of $33,061 and a median home value of $84,700, wanted to remain separated from the neighboring poverty. For example, in February 2013, news articles reported that Chickasaw put up physical barricades along a road connecting Chickasaw and Prichard, which some speculated were meant to keep Prichard residents out of Chickasaw neighborhoods.[209] Though Chickasaw leaders claimed the barriers were a precursor to roadwork, they remained in place for months without any work taking place. Incidents like these suggest that Chickasaw, though not quite as White and affluent as places like Saraland and Satsuma, was pushed to secede by a desire to remain separate from the even poorer and less White Prichard.

Finally, the impending split in Satsuma spurred on the one in Chickasaw. Chickasaw leaders recognized that if Satsuma split and took control of its school buildings, about 100 Chickasaw students who were zoned to Vigor and Blount High Schools in Prichard, but received transfers to attend Satsuma High School, would no longer be able to attend.[210]

In March 2009, the Chickasaw City Council voted to commission a study on the feasibility of starting its own school system.[211] The City Council then surprised some with its November 2010 announcement that it would be splitting off and putting together a new school board.[212] By January 2011, the City Council had formed a school board and began plans to ask its citizens to pay more in taxes to fund the new system.[213] But it never put the overall secession decision to a vote in the city, as this was not (and still is not) required by state law.[214]

The Satsuma and Chickasaw secessions were even more contested and complicated than the Saraland split. In August 2011, MCPSS leaders announced they were prepared to take legal action to prevent Chickasaw and Satsuma from leaving.[215] They argued Mobile County was exempt from the Alabama law allowing for municipalities to leave county school districts since MCPSS formed before the state department of education. They also expressed worries about the quality of the proposed school districts and the cities’ abilities to fund their own systems. MCPSS school board President Ken Megginson suggested Chickasaw did not have enough of a tax base to support its own system: “When I drive through, I see a Whataburger and a Huddle House. How are they going to be able to afford to provide these children an opportunity to follow their dreams?”[216] Prior to taking any legal action, MCPSS leaders tried to offer concessions to Satsuma and Chickasaw in an effort to prevent the separations. During negotiations in August and September 2011, they offered to allow children in the two cities to attend schools in their communities to assuage parents who complained of faraway schools. They also offered to renovate school buildings in the two cities, but Chickasaw leaders in particular expressed distrust of any promises from the school board.[217]

Complicating negotiations, MCPSS angered Chickasaw officials in October 2011 when they removed playground equipment from the city’s Hamilton Elementary School. MCPSS facilities manager Tommy Sheffield said the equipment was needed at an elementary school in Prichard and denied accusations that the acts were taken in response to Chickasaw’s impending split. He stated, “At this point, we’re just filling orders we have within our district for our children. This has nothing to do with the politics.”[218]

After months of negotiations, Chickasaw and Satsuma signed their official secession agreements with MCPSS in April 2012, only after state superintendent Tommy Bice stepped in to help mediate.[219] The agreements outlined the following.

Chickasaw acquired the three school buildings within its limits: Hamilton Elementary School, Chickasaw School of Mathematics and Science (an elementary magnet school), and Clark-Shaw Magnet School (a middle magnet school). MCPSS was allowed to lease the Hamilton Elementary building back for another four years (by forgiving Chickasaw $100,000 in construction debt) in order to operate its elementary magnet school for math and science.[220] Upon opening in 2012–13, Chickasaw City School District placed all of its students in the building that used to house Clark-Shaw Magnet School and renamed this school Chickasaw City High School. When Chickasaw gained custody of the old Hamilton Elementary building in 2015–16, they moved PK-5 grade students there and renamed it Chickasaw City Elementary School. Students in grades 6-12 remained at the high school. Satsuma also acquired three buildings within its town limits: the former Robert E. Lee Primary Elementary School, Robert E. Lee Intermediate Elementary School, and Satsuma High School.

Most students residing in Chickasaw and Satsuma would not be allowed to enroll in MCPSS magnet schools without paying the out-of-district tuition fee. But students in grades 11 and 12 would be allowed to stay in MCPSS schools until they graduated, and special education students enrolled at the county’s Augusta Evans Special School and the Regional School for the Deaf and Blind would be allowed to remain enrolled as well, for up to four more years.[221] However, the new school districts had to reimburse MCPSS for the costs of these students and their transportation. Neither new district would owe MCPSS for previous school renovations.[222]

In order to accommodate students displaced by these splits, MCPSS redrew a few of its school attendance boundaries. North Mobile County Middle School in Axis became a K-8 school to accommodate elementary students who used to attend Satsuma’s elementary schools but didn’t live within the municipality. And students in that area who used to attend Satsuma High School were rezoned to Citronelle High School, twenty miles away.[223]

Despite the race-evasive language used to advocate for these splits, the school district secessions within Mobile County had clearly racialized outcomes. Here, we detail the implications of each secession and the racially disparate effects on the schools that seceded and those left behind in MCPSS. Because the seceding communities talked about secession as a community development strategy, we consider the population characteristics as well as school enrollment. Given the outcomes we witness in Mobile County, we explore what the current legal and political contexts permitting secession mean for public schools and for democracy in this racially diverse metropolitan area.

While Saraland, Satsuma, and Chickasaw all differed racially and economically from Mobile County as a whole before secession, the splits have furthered the segregation between these residential areas (See Table 2). In addition to segregating residents of different races, the secessions have increased the segregation of economic resources. For example, Saraland has become increasingly more affluent than the county as a whole since it created its own school district. In 2000, Saraland’s median household income was 14% greater than that of Mobile County, while the median home value was slightly less than that of the county overall. But as of 2019, Saraland’s median household income was 27% greater than the county’s, and the median home value was about 14% higher than that of the county. The economic growth of both Saraland and Satsuma lends justification to the earlier race-evasive rationale voiced by community leaders in advocating for separate districts, regardless of the segregative effects on the larger region.

| Table 2: Residential Household Characteristics[224]ψ | ||||||

| Location | Population | Median Household Income | Median Home Value | |||

| Value | Percentage of county figure | Value | Percentage of county figure | |||

| 2000 | ||||||

| Saraland City | 12,288 | $38,318 | 113.7 | $79,300 | 95.5 | |

| Satsuma City | 5,687 | $50,496 | 149.8 | $93,300 | 116.0 | |

| Chickasaw City | 6,364 | $27,036 | 80.2 | $56,000 | 69.6 | |

| COUNTY | 399,843 | $33,710 | 100.0 | $80,500 | 100.0 | |

| 2010 | ||||||

| Saraland City | 13,405 | $48,721 | 118.9 | $130,100 | 102.9 | |

| Satsuma City | 6,168 | $59,289 | 144.6 | $145,900 | 115.4 | |

| Chickasaw City | 6,106 | $33,061 | 80.6 | $84,700 | 67.0 | |

| COUNTY | 412,992 | $40,996 | 100.0 | $126,400 | 100.0 | |

| 2019 | ||||||

| Saraland City | 16,171 | $60,633 | 127.4 | $149,000 | 114.4 | |

| Satsuma City | 6,749 | $64,348 | 135.2 | $155,800 | 119.7 | |

| Chickasaw City | 6,457 | $28,611 | 60.1 | $75,500 | 58.0 | |

| COUNTY | 414,809 | $47,583 | 100.0 | $130,200 | 100.0 | |

And by separating residential areas within the county by way of school district boundary lines, local leaders have certainly affected the larger region. In particular, the secessions cordon off economic resources and reserve them for small areas rather than allowing them to be more equitably distributed among all students within the county. In the 2017–18 school year, the per pupil expenditures funded through local sources totaled $1,896 in Saraland and $2,202 in Satsuma, compared to $1,656 in MCPSS and $1,252 in Chickasaw. Though state and federal sources help to partially mitigate the discrepancies, the school district secessions have segregated local resources among areas with drastically different racial and economic characteristics, creating Whiter areas with more affluent students and schools, while leaving areas with higher shares of Black residents with less affluent students and schools.

Saraland in particular has also seen substantial geographic and population growth as surrounding homeowners petition for annexation into the municipality. According to the Mobile County GIS website, there were 230 separate annexations between 2006 and 2020. Census counts show the city’s population increased by 32% between 2000 and 2020, and the school district has doubled its enrollment since it first opened. The fact that families continue to buy in to seceded areas like Saraland speaks to the political acceptability of secession as a mechanism to segregate students and separate resources. It also demonstrates how schools perceived to be of high quality, especially segregated White ones, become exclusive and available only to those with the economic resources and racial privilege to buy access (by purchasing a home in Saraland, for example), rather than remaining fully accessible public goods that publicly funded education ought to be.

Similar to the differences in residential populations, there are stark differences in the student populations of each school district. Total public school enrollment in the county decreased by about 4,000 students in the twelve years following the first secession (See Table 3). However, the seceded districts saw their combined enrollments grow to over 6,300 students by 2019–20, while MCPSS has experienced steep declines of more than 10,000 students. Furthermore, as MCPSS has seen a decreasing percentage of White students in recent years, Saraland’s and Satsuma’s districts remain substantially Whiter than the county district. Saraland and Satsuma also have relatively low percentages of students who qualify for free- and reduced-price lunch (a proxy measure of students’ socioeconomic status), especially as compared to MCPSS and Chickasaw City, before those districts began offering free lunch to all students.

| Table 3: School District Enrollments by Student Race/Ethnicity and Low-Income Status[225]ψ | |||||||

| District | Enrollment | %White Students | %Black Students | %Hispanic Students | %Other Races[226]¥ | % Free/

Reduced Lunch Students |

|

| 2007-2008 | |||||||

| MCPSS | 64,461 | 45.1 | 50.4 | 1.3 | 3.2 | 63.0 | |

| 2008-2009 | |||||||

| MCPSS | 62,225 | 44.3 | 50.9 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 65.1 | |

| Saraland City | 1,528 | 77.7 | 19.1 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 55.2 | |

| TOTAL | 63,753 | 45.1 | 50.1 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 64.9 | |

| 2012-2013 | |||||||

| MCPSS | 58,625 | 42.9 | 50.9 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 73.5 | |

| Saraland City | 2,526 | 81.1 | 14.7 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 51.1 | |

| Satsuma City | 1,463 | 86.9 | 10.9 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 42.0 | |

| Chickasaw City | 864 | 27.0 | 70.3 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 88.3 | |

| TOTAL | 63,478 | 45.2 | 48.8 | 2.0 | 3.9 | 72.1 | |

| 2019-2020 | |||||||

| MCPSS | 53,941 | 39.0 | 49.7 | 4.9 | 6.4 | | |

| Saraland City | 3,233 | 72.1 | 16.7 | 2.8 | 8.4 | 43.1 | |

| Satsuma City | 1,592 | 84.4 | 9.2 | 1.4 | 5.0 | 39.3 | |

| Chickasaw City | 1,514 | 33.4 | 58.7 | 4.4 | 3.6 | | |

| TOTAL | 60,280 | 41.8 | 47.1 | 4.6 | 6.4 | | |

When looking at levels of multiracial school segregation within Mobile County over time, we find that the percentage of the overall school segregation caused by segregation between school districts has increased substantially (Table 4). The increase was inevitable, as the contribution of district boundary lines to overall segregation was, by definition, zero in the years before secession. The consistent increases in this percentage over time are concerning because increases in multiracial school segregation are unlikely to be addressed through common district assignment policies. In particular, the increases in the percentage of overall segregation due to segregation between districts seen since the last secessions in 2012 show that the seceded areas are becoming less and less similar to the county over time. As of the 2019–20 school year, almost one tenth of the total school segregation seen in the county was due to the segregation across district boundary lines, while the remainder was due to segregation within school districts.

| Table 4: Multiracial Levels of Segregation (Theil’s H) in Mobile County | ||||

| Schoolyear | Number of districts | Overall school segregation | Segregation between school districts | Percentage of overall school segregation due to segregation between school districts |

| 2007-08 | 1 | 0.397 | 0.000 | 0.0 |

| 2008-09 | 2 | 0.389 | 0.007 | 1.7 |

| 2009-10 | 2 | 0.380 | 0.008 | 2.1 |

| 2010-11 | 2 | 0.366 | 0.010 | 2.8 |

| 2011-12 | 2 | 0.356 | 0.012 | 3.4 |

| 2012-13 | 4 | 0.353 | 0.027 | 7.5 |

| 2013-14 | 4 | 0.348 | 0.026 | 7.4 |

| 2014-15 | 4 | 0.344 | 0.027 | 8.0 |

| 2015-16 | 4 | 0.334 | 0.028 | 8.5 |

| 2016-17 | 4 | 0.322 | 0.028 | 8.8 |

| 2017-18 | 4 | 0.309 | 0.028 | 9.1 |

| 2018-19 | 4 | 0.305 | 0.029 | 9.4 |

| 2019-20 | 4 | 0.293 | 0.028 | 9.6 |

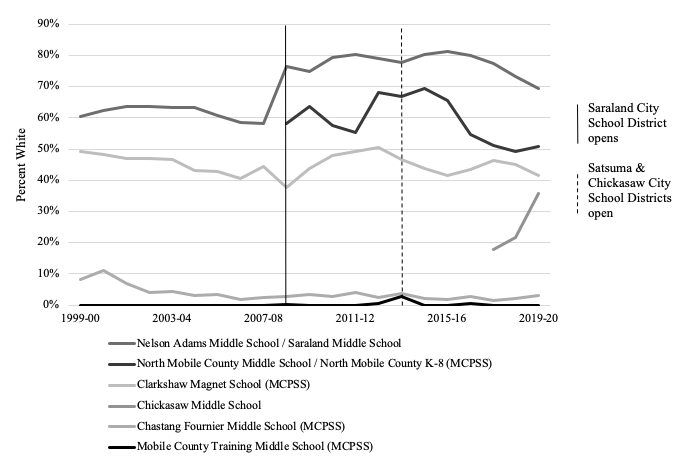

The overall trends point to the increasing role of district boundary lines in perpetuating segregation overall, but even these trends mask more detailed patterns in the schools most directly affected by the secessions. To analyze these patterns, we next offer a separate examination of the school-level demographic changes within schools located in Saraland, Satsuma, Chickasaw, and neighboring northern Mobile County communities.

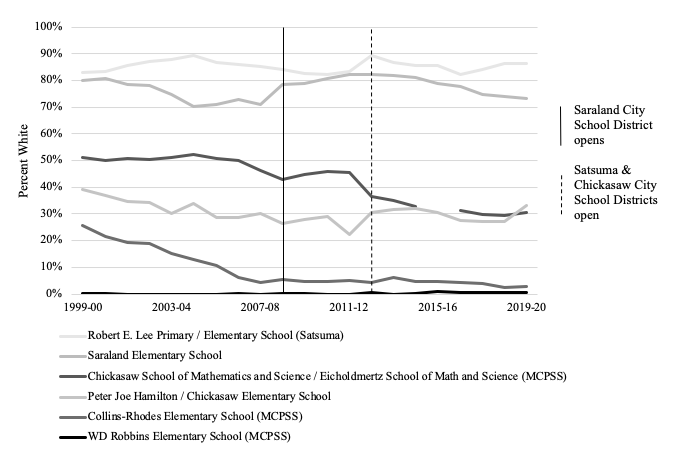

First, we analyze elementary schools within the area (See Figure 5). MCPSS’s Saraland Elementary School became part of Saraland City Schools in 2008–09 and saw its White population increase from 71% in 2007–08 to 79% in the following year. Since then, the school has maintained a population that is more than three-quarters White. In Satsuma, the MCPSS schools known as Robert E. Lee Primary School and Robert E. Lee Intermediate School consolidated to become Robert E Lee Elementary School in 2012–13 when Satsuma City split and acquired the building. This building saw an immediate increase in its percentage of White students from 82% to 89% following the secession, and in 2019–20, it remained 86% White. Similarly, MCPSS’s Hamilton Elementary School was renamed Chickasaw Elementary School in 2012-13 when Chickasaw split. Since seceding, Chickasaw Elementary School has remained about one-third White.

Meanwhile, nearby MCPSS schools have experienced decreasing populations of White students in recent years. Collins-Rhodes Elementary School has an attendance zone that neighbors the western edge of Saraland and Chickasaw, and since 2006–07, it has had a student population that is only about 5% White. Similarly, W.D. Robbins Elementary School sits to the south of Chickasaw in Prichard and has been almost entirely Black for the past twenty years. While Chickasaw Elementary is not as overwhelmingly White as schools in its fellow secession districts, it certainly has a higher percentage of White students than neighboring schools in Prichard. Finally, the Chickasaw School of Mathematics and Science was an MCPSS elementary magnet school located in Chickasaw that was moved to the southwest area of Mobile City and renamed the Eichold-Mertz School of Math and Science after Chickasaw seceded. This once racially integrated school was 49% Black and 51% White in 1999–2000. However, it has seen a steadily decreasing percentage of White students over the years, especially since the Chickasaw split in 2012.

Figure 5: Percentage of White Students in Elementary Schools in North Mobile County[227]