The Fuzz(y) Lines of Consent: Police Sexual Misconduct with Detainees

By

By

Katherine A. Heil[1]*

In October 2017, two New York City police officers were charged with the first-degree rape and kidnapping of an eighteen-year-old woman in their custody.[2] The alleged incident took place on the night of September 15, 2017 when Anna Doe, the eighteen-year-old victim, drove to a park in Brooklyn with two male friends to “smoke pot.”[3] As Anna and her friends drove down a dirt road in the park around 8:00 PM, she noticed an unmarked van following behind her in the dark.[4] Police sirens flashed and the teens then realized the van was an undercover New York City Police Department (NYPD) van.[5] Although “[n]o facts available to the police g[a]ve rise to reasonable suspicion that Doe was committing a crime,” Detectives Eddie Martins and Richard Hall pulled Anna’s vehicle over;[6] the plainclothes officers approached her car and subsequently discovered the presence of marijuana.[7]

Minutes after pulling Anna and her friends over, Detectives Martins and Hall let the two male passengers go, but handcuffed Anna and placed her into the police van.[8] The two Detectives then assaulted eighteen-year-old Anna and forced her to “expose parts of her body,” before driving her in the police van to a nearby restaurant parking lot.[9] Thereafter, Detectives Martins and Hall forcibly sexually assaulted and raped her.[10]

The sexual assault did not end there. The Detectives drove Anna around Brooklyn, taking turns sexually assaulting her in the back of the police van.[11] Once the attack was over, Detectives Martins and Hall released Anna near an NYPD precinct without charging her with a crime.[12] Anna went to the hospital later that same evening and “communicated to the hospital staff that she was raped by two plainclothes police officers.”[13] The hospital performed a rape test and the city medical examiner’s office concluded the DNA recovered from the teen “contained samples of both detectives’ sperm.”[14]

A fifty-count indictment was issued against the two NYPD detectives, charging them with rape, kidnapping, and official misconduct.[15] At their arraignment in Brooklyn Supreme Court, Martins and Hall both pled not guilty and claimed the encounter was consensual.[16] “The facts of [this] case are bad enough, but they also underscore another outrage: Vaguely written statutes in many states, including New York [at the time], permit police officers to escape sexual assault charges by claiming that the victims consented to the act.”[17]

Most would presume that states have laws prohibiting law enforcement officers from engaging in sexual acts with individuals in police custody.[18] Thirty-one states, however, have an alarming “loophole” in their laws that allow for police officers to legally have consensual sex with individuals in their custody.[19] “This oversight by lawmakers can be—and has been—detrimental to the application of justice.”[20]

Anna Doe’s horrifying experience recently brought to light the egregious consequences of this legal loophole.[21] This case underscores a “chronic problem” of police sexual misconduct[22] and the failure of many states to provide laws necessary to protect their citizens from such a raw abuse of power.[23] While the officers involved in such misconduct are not representative of the hundreds of thousands of officers who honorably serve and protect their communities each day, their wrongdoing is detrimental to the public’s relationship with law officials and “interferes with police officers’ ability to effectively perform their duties.”[24]

Due to police officers’ uniquely powerful position over individuals in their custody,[25] any sexual interaction between the two is fundamentally non-consensual[26] and state laws need to reflect this fact.[27] The State of South Carolina is one of thirty-one states that does not have a law addressing sexual conduct between a police officer and an individual in police custody.[28] This Note argues that the South Carolina Legislature should pass a statute to criminalize sexual encounters between police officers and individuals in their custody and to explicitly reject consent as a defense to such acts. The enactment of such a law would provide individuals in police custody the same protections afforded inmates in South Carolina’s correctional facilities.

Part II of this Note provides a background of sexual misconduct in correctional facilities, including the development of laws asserting that an inmate is not capable of providing consent to sexual acts with corrections staff. Part III explains how the law enforcement consent loophole is problematic. Part IV details the bills passed in other states to close the law enforcement consent loophole. Part IV further details the failed federal bill that would have addressed this issue. Finally, Part V provides a detailed overview of the proposed South Carolina bill that would close the consent loophole in the State’s law and proposes broader recommendations intended to help the State address the problem of police sexual misconduct.

Sexual misconduct by police officers has received relatively little legal or scholarship analysis.[29] In comparison, legal scholars and government entities have paid substantial attention to the sexual victimization of inmates by correctional staff.[30] Correctional administrators reported 24,661 allegations of sexual victimization in adult correctional facilities in 2015 alone.[31] More than half (58%) of the allegations involved sexual victimization of inmates by correctional facility staff.[32] Similarly, a survey conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) found that more prisoners reported sexual victimization perpetrated by corrections staff than reported sexual victimization perpetrated by other inmates.[33]

Sexual abuse of female inmates by male staff, in particular, is noted to be “notorious and widespread” in the United States.[34] While women constitute a small percentage of the total inmate population,[35] they are at a remarkably high risk of sexual assault by correctional staff.[36] Several factors account for the high risk of sexual abuse by guards in women’s prisons. Some explanations include the presence of cross-gender supervision,[37] poorly designed facilities,[38] and the fact that most prisoners have been sexually assaulted or physically abused in past relationships.[39]

With the public’s continued increased awareness of staff sexual misconduct with inmates,[40] the federal government—and all fifty states—criminalized sexual contact between guards and prisoners.[41] Nonetheless, these laws have proven to be largely ineffective and have failed to prosecute offending correctional officers effectively.[42] Following an allegation of sexual victimization, correctional facilities conduct an investigation and classify it as fitting into one of three categories: unfounded (determined not to have occurred), substantiated (determined to have occurred), or unsubstantiated (insufficient evidence to determine if the sexual victimization occurred).[43] Nearly half of staff-on-inmate sexual victimization cases from 2012 to 2015 were determined to be unsubstantiated.[44] For the small percentage of cases found to be substantiated, less than half were referred for prosecution.[45] The underlying belief that many of these sexual encounters between staff and inmates are consensual is one reason for the lack of prosecutions.[46]

Despite the common assertion that sexual encounters between correctional officers and inmates are often consensual,[47] by law, prisoners are generally considered unable to give consent to sexual conduct with correctional officers.[48] A prisoner’s inability to give consent is based on several factors. First, staff members and inmates are in inherently unequal bargaining positions.[49] Second, staff members who engage in sexual relations with inmates may be exploiting inmates’ past sexual abuses or other vulnerabilities, whether knowingly or unknowingly.[50] Third, inmates may try to use sexual acts in exchange for prohibited items or privileges—which is dangerous to the safety and security of the prison.[51]

Furthermore, laws prohibiting the consent defense are representative of contemporary “common standards of decency.”[52] By 2006, all fifty states had statutes criminalizing sexual relations between prison staff and inmates,[53] and the number of states prohibiting the consent defense to sexual contact between prison staff and inmates has increased over the past decade.[54] This increase is in keeping with the fact that “[a] majority of people in the United States . . . do not believe permitting legal ‘consent’ to sexual contact between prisoners and guards is a decent legal practice.”[55] Consequently, the consent defense—in the custodial context—is legally unsound and contrary to common standards of decency.[56]

According to federal law, any sexual relations or sexual contact between a prisoner and a correctional staff is illegal.[57] Importantly, consent is never a legal defense under federal law for sexual acts between an inmate and correctional staff; therefore, all sexual relations between inmates and staff are considered abuse.[58] In addition to federal criminal statutes, the federal government—officially recognizing the problem of sexual abuse in prison—enacted the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) in 2003.[59] The PREA required the gathering of national data on allegations of prison rape, called for national standards for the reduction and punishment of prison rape, and made grants to states for assisting in these efforts.[60] Most state laws are aligned with the federal standards and explicitly reject consent as a defense in the custodial context.[61]

South Carolina law explicitly states that consent is never a defense to sexual acts between inmates and correctional staff.[62] Although the South Carolina Department of Corrections (SCDC) has a zero-tolerance policy regarding sexual misconduct against inmates,[63] inmates still fall victim to sexual assault in South Carolina correctional facilities every year.[64] SCDC submits annual reports regarding inmate sexual victimization to the BJS, which is responsible for collecting data under the PREA.[65] According to the SCDC survey responses, there were 330 reports of staff sexual misconduct and harassment of inmates from 2012 to 2017.[66] Of the 330 reported, over fifty-four percent were labeled unsubstantiated.[67]

This high number of reported instances demonstrates that South Carolina is not immune from the problem of sexual misconduct by correctional facility staff. While South Carolina has attempted to address issues of staff sexual misconduct within correctional facilities, victims of police sexual misconduct are ignored outright.[68]

A substantial majority of states—including South Carolina—have laws explicitly stating that inmates are not capable of consenting to sexual conduct with law enforcement officers.[69] At the same time, most states—and the federal government—do not have laws which determine whether those in police custody can consent to sexual acts with police officers or other law enforcement personnel.[70] This gap in the law—the “consent loophole”—allows for law enforcement officers, charged with sexual misconduct against an individual in their custody, to admit to the conduct but claim it was consensual.[71]

Currently, the consent loophole exists in South Carolina. South Carolina Code of Laws Section 44-23-1150 criminalizes “sexual misconduct with an inmate, offender or patient.”[72] Under this statute, the only “actors” that can be guilty of sexual misconduct are “employee[s], volunteer[s], agent[s], or contractor[s] of a public entity that has statutory or contractual responsibility for inmates or patients confined in a prison, jail, or mental health facility.”[73] The statute defines “victim” as an “inmate or patient who is confined in or lawfully or unlawfully absent from a prison, jail, or mental health facility, or who is an offender on parole, probation, or other community supervision programs.”[74] The statute continues to state that “[a] victim is not capable of consent for sexual intercourse or sexual contact with an actor.”[75] Therefore, this Section does not protect individuals who are neither inmates nor patients, but who are nonetheless in police custody, such as suspects.

South Carolina’s acknowledgment of an inmate’s inability to consent to sexual acts with law enforcement officers exemplifies a fundamental recognition of the imbalance of power between law enforcement officers and individuals in their custody.[76] Few people are aware that a consent loophole even exists for police officers and those in their custody.[77] Nonetheless, “[t]he policy rationale for barring consent as a defense to allegations of sexual misconduct against a police officer is similar to that for criminalizing sex between an inmate and a corrections officer.”[78]

Like corrections officers, police officers—and other law enforcement officers—are in a position of high authority.[79] Police officers’ authority to detain and arrest citizens creates a power dynamic that makes on-duty sexual activity seem fundamentally forbidden.[80] Indeed, studies have found that physical violence is not a prerequisite for police sexual violence—police officers can “instead rely[] on threats and quid pro quo inherent in police authority and power.”[81] Police and correction officers encounter similar types of persons and personalities within their jobs—both encounter citizens engaged in criminal behavior, which according to researchers, increases the likelihood of police sexual misconduct.[82] More generally, the citizens they encounter are particularly vulnerable because many are victims “or perceived as ‘suspicious’ and subject to the power and coercive authority granted to police.”[83]

Moreover, police work inadvertently provides a job environment that is conducive for sexual misconduct.[84] Police officers are in a unique position to commit acts of sexual misconduct because of their inherent authority as enforcers of the law, frequent interactions with various citizens, and the unsupervised nature of patrol work.[85] Many researchers have also suggested that police departments’ “culture of misogyny and invulnerability” has further contributed to the problem.[86] In particular, research suggests that police culture has “masked” police sexual misconduct—and in turn—created an environment for predators to continue engaging in such behavior.[87] These aspects of police culture are present in both correctional facilities and police departments—perhaps a consequence of the male-dominated nature of the law enforcement field.[88] Accordingly, one study examined 548 cases involving police arrests for sex-related crimes between 2005 and 2007, and its results stated that male officers perpetrated nearly all of the acts.[89]

Sexual abuse, in general, is significantly underreported, and even more so when the perpetrators are the police.[90] The true scope of police sexual misconduct is unknown because—unlike instances of sexual abuse by corrections officers—there is no duty for police departments to record or report incidences of police sexual misconduct.[91] This underreporting is further perpetuated by a victim’s fear of reporting an assault by a police officer—to the police.[92] There are a variety of reasons for victims’ reluctance to report assault, including fear of retaliation, fear of not being believed, and the idea that a sexual encounter with a police officer will always be deemed consensual.[93]

Despite the “blue wall of silence,”[94] researchers have been able to find enough evidence to conclude that police sexual misconduct is a significant problem.[95] “Even police officers agree with this conclusion.”[96] Researchers have used several methods to tackle this blue wall of silence, including surveying police officers directly about their first and secondhand knowledge of police sexual misconduct and through reviews of news media reports.[97]

Although these research studies have had varying statistical results, one factor remains consistent: police sexual misconduct is relatively common.[98] In fact, sexual misconduct is the second most frequently reported type of police abuse.[99] The Cato Institute concluded that “sexual assault rates are significantly higher for police when compared to the general population.”[100] Police sexual misconduct is not a new observation, hence one study in 1978 which referred to the police car as a “traveling bedroom.”[101] This 1978 study found that forty-four percent of the officers participating in the study reported between ten percent to one hundred percent of their fellow officers have engaged in sexual conduct on duty.[102] A more recent study in 2003 found that thirty-five percent of all officers engage in some form of sexual misconduct.[103]

The most sweeping investigations into police sexual misconduct occurred in 2015 by both The Associated Press and The Buffalo News.[104] The Associated Press obtained records from forty-one states on police decertification and found that some 990 law enforcement officers were decertified between 2009 and 2014 for sexual misconduct.[105] The Buffalo News investigation used news reports and court records to compile a database of over 700 credible cases of job-related sexual misconduct by police officers in the past decade.[106] According to the database, “a law enforcement official was caught in a case of sexual abuse or misconduct at least every five days.”[107] Even more, researchers agree this number is just the “tip of the iceberg.”[108]

Of even greater concern, studies have found that despite the high number of reports, “it is unlikely that most police officers will face major consequences for their actions.”[109] One reason for the lack of punishment is that many officers claim the sexual encounter was consensual when faced with overwhelming evidence of sexual abuse.[110] Indeed, consent is the most frequently used defense by police officers acquitted in sexual assault cases.[111] Furthermore, one study found that one in every six police officers charged with sexual abuse were later acquitted—or had the charges dropped—in response to their claim that the sexual encounter occurred but was consensual.[112] Most states that allow consent as a defense can only charge the offending officer with “official misconduct,” a misdemeanor with a maximum sentence of only one year.[113] This too accounts for the lack of criminal prosecution.

South Carolina is not immune to the problem of police sexual misconduct, which is of consequence considering the presence of the consent loophole.[114] From 2005 to 2013, fifty-seven police officers in South Carolina were arrested for “sex-related” offenses.[115] Around half of these arrests also involved “violence-related” crimes, which suggests the other half supports the misconceived proposition that police sexual misconduct “frequently involves consensual behavior.”[116] Consequently, only twenty-nine of the fifty-seven officers arrested received convictions, illustrating how the availability and use of the consent defense hinder the enforcement of punishment for police sexual misconduct.[117]

More recently, the South Carolina legislature found that since 2010, at least ten South Carolina police officers resigned or were fired because of sexual misconduct allegations by individuals in their custody.[118] Several of these cases were difficult to prosecute, as some officers claimed the sexual encounters were consensual.[119] Also, a few of the officers only faced charges of “misconduct in office,” as opposed to sexual assault or rape.[120] Available data shows that police sexual misconduct undoubtedly occurs within South Carolina—and the current law allows for police officers to escape liability and punishment for such harmful misconduct.

The case of Charleston, South Carolina police officer Joseph DiMeglio exemplifies the issues with consent, victim hesitation to report a police officer, and lack of punishment.[121] DiMeglio resigned amidst allegations of sexual assault of a twenty-three-year-old woman.[122] DiMeglio admitted to having sex—while in uniform—with the woman on the trunk of his police cruiser but insisted the incident was consensual.[123] The facts and circumstances surrounding the night of the incident, however, cast doubt on whether the encounter was in fact consensual. The alleged victim, drunk at the time of the sexual encounter, sent a text message following the incident to another Charleston police officer with the photograph of a large bruise on her thigh and the statement, “if you only knew how that happened.”[124] Later that same night, the alleged victim sent another text message to her former boyfriend stating that a city police officer had just raped her.[125] The former boyfriend then reported the incident to police.[126] When detectives questioned the woman, however, she claimed that she could not remember whether she consented and stated that she did not want to file charges.[127] Despite a police investigation into this complaint, authorities determined the allegation was unfounded, and DiMeglio did not face any charges.[128]

Another particularly disturbing case is that of Dereck Johnson.[129] Johnson was a police officer in Elloree, South Carolina when he responded to a domestic dispute call on June 12, 2016.[130] When Johnson and another officer arrived on the scene, they separated the couple, and Johnson remained inside the house with the woman while the other officer took the male outside.[131] The woman alleged that Johnson threatened her to perform an oral sex act or she would be sent to jail.[132] Johnson admitted that the woman performed an oral sex act on him, but claimed it was consensual.[133]

At the preliminary hearing, Johnson’s attorney claimed the sexual act was consensual and further stated, “the true victim in this case arguably is Dereck Johnson” who was “seduced to do this activity.”[134] Ultimately, Johnson pled guilty to misconduct in office and only received a suspended sentence of three years’ probation and one hundred hours of community service.[135] This case is an unfortunate example of how the consent defense allows police officers in South Carolina to escape adequate consequences for on-duty sexual misconduct against the very citizens they are meant to protect. Research has shown that officers frequently “prey on domestic-violence survivors, who are particularly vulnerable to abuses by people they call on for protection.”[136] Contrary to argument put forth by Johnson’s attorney, the real victim is the domestic-violence survivor who was in no position to give consent to a police officer whose presence was to interrupt a domestic disturbance.

DiMeglio and Johnson are only two examples of sexual misconduct by police officers in South Carolina. Since 2006, at least 158 police officers in South Carolina were charged with sexual battery, sexual assault, or unlawful sexual contact with a person in custody.[137] Twenty-six of these officers were acquitted as a result of a consent defense.[138] The power imbalance between a police officer and an individual in their custody is so significant that consent should never be allowed as a defense to sexual misconduct by the police officer.[139] Moreover, the seriousness of the offense[140] necessitates action by the South Carolina General Assembly.

The ability of police officers to claim that sexual acts with a person in police custody were consensual is problematic for moral and ethical reasons—and especially since it undermines the legal community and harmfully diverts law enforcement resources. Police officers and other law enforcement officers are tasked with the ever-important duty to serve and protect its citizens; “police sexual behavior at the very least violates widely accepted ethical standards commonly associated with law enforcement.”[141]

The IACP described such behavior as “particularly egregious violations of trust and authority” and stated, “[s]ituations where officers engage in sexual misconduct and victimize those they are sworn to protect and serve amount to civil rights violations.”[142] Police officers—and the power and respect that they wield as officers of the law—should not be able to offer the defense of consent as a defense to sexual acts perpetrated against those they have broad discretionary power over.[143] Indeed, the judge in the Dereck Johnson case acknowledged that Johnson’s acts were against basic common sense and stated Johnson should know what is “absolutely inappropriate,” regardless of a lack of police training on such a situation.[144] It is critical that laws regarding sexual consent reflect such a “common-sense principle that people whom the police have placed under arrest are legally incapable of consenting to sexual acts with officers, who hold enormous power over them.”[145]

The power imbalance between a police officer and an individual in their custody is so significant that any sexual encounter between the two is fundamentally non-consensual and an egregious abuse of power.[146] The notion that many victims of police sexual misconduct are willing participants who initiate the sexual encounters[147]—or offer sexual acts in exchange for favors or as a “get out of jail free card”[148]—is undermined by the fact that the sexual act is nonetheless motivated by, or at the very least related to, the officer’s position of power.[149] Evidence suggesting that people do not feel free to decline police officer’s request to conduct a consent search supports the idea that a citizen cannot freely consent to sexual acts in such an inherently coercive situation.[150] If individuals are afraid to decline an officer’s request to search something as simple as their car, then it seems plausible that fears of a greater extent arise when consenting to sexual acts with a police officer. The Supreme Court recognized the inherently coercive nature of custodial surroundings in interrogation settings,[151] and yet, South Carolina law fails to recognize the inherently coercive nature present in instances of on-duty sexual misconduct.[152]

Additionally, allowing police officers to engage in consensual sexual misconduct with individuals in police custody undermines the legal community.[153] The law enforcement officers engaged in such acts have an enormous impact on both their departments and the community, “crippling relationships with an already weary public and scarring victims with a special brand of fear.”[154] Officers that engage in sexual conduct with individuals in police custody exceed the scope of authority entrusted in them by the public,[155] which damages the public’s trust in—and respect for—law enforcement.[156] Moreover, the lack of criminal prosecution for such conduct often allows the offender to continue in police employment, placing more citizens at risk and further undermining faith in the criminal justice system.[157] For example, in South Carolina, the Horry County Police Department conducted at least thirteen investigations into allegations of police sexual misconduct between 2006 and 2016.[158] The department allegedly failed to properly address the sexual misconduct and allowed the offending officers to resign, thereby permitting them to transfer to other law enforcement agencies without record of their alleged misconduct.[159]

Furthermore, law enforcement time and resources are harmfully diverted as a result of police sexual misconduct.[160] Sexual misconduct “interferes with police officers’ ability to effectively perform their duties” and can even be a danger for fellow officers.[161] One police officer, in response to a survey of officers’ perceptions and frequency of police sexual misconduct, reported that one night when he was on shift, he responded to other officers’ calls because they were engaged in sexual misconduct while on duty.[162] This police officer rightfully questioned, “What if I needed some back-up?”[163] This concern is even more alarming given that a majority of cases involving adult victims of police sexual misconduct occur when the offending officer is on duty.[164] In response to a lack of criminal prosecution, many victims have also turned to civil remedies, “miring departments in litigation that leads to costly settlements.”[165] The victim in the Dereck Johnson case brought civil actions against the Orangeburg County Sheriff’s Office and former Deputy Johnson.[166] The civil matter settled for $350,000 and was paid by the South Carolina Insurance Reserve Fund.[167]

Finally, consensual sex is problematic between a law enforcement officer and an individual in police custody because individuals in police custody are often particularly vulnerable.[168] Perpetrators in the law enforcement context often target the most vulnerable people—specifically drug addicts, sex workers, women of color, victims of domestic abuse, young women, and people with a history of criminal activity—to reduce the risk that such abuse will be reported, and to ensure their credibility over that of the victim.[169] “In short, such an individual is the perfect victim against whom to commit a crime and get away with it.”[170]

Allowing consent as a defense to sexual acts between law enforcement officers and individuals in police custody is not only devastating to the victims,[171] but also encourages more of the same conduct.[172] It is imperative that South Carolina close the consent loophole and enforce criminal punishment for police sexual misconduct. “Only then will predators with badges begin to think twice about how they behave toward the citizens they are meant to protect.”[173]

As societal and legal awareness of the prevalence of police sexual misconduct increases, more and more states will presumably adopt criminal statutes to explicitly reject the ability of individuals in police custody to consent to sexual acts with police officers or other law enforcement officials.[174] “Across the country, police departments are being pushed to confront longtime patterns of abuse.”[175] In recent years, more states have closed the consent loophole, “applying to cops the same rules already in place nationwide for probation officers and prison and jail guards.”[176] Many states, however—including South Carolina—have not, “partly because few people realize the loophole exists.”[177] Therefore, increasing the public’s awareness of the issue is an important step towards closing the consent loophole.

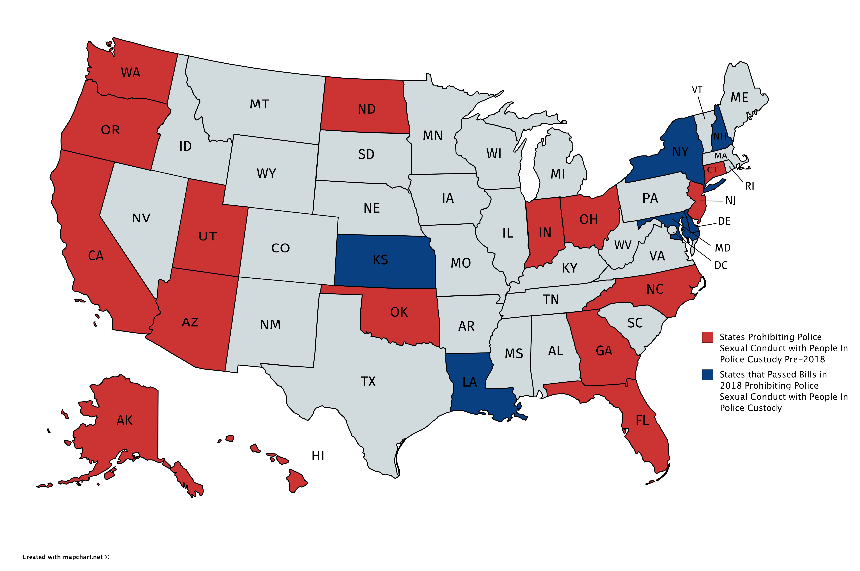

The loophole present in many state laws gained public attention in late 2017 in wake of Anna Doe’s case in New York.[178] Prior to Anna’s case, only fifteen states[179] had statutes that provided an individual in custody may not give consent to sexual acts with a law enforcement officer.[180] In 2018, six more states passed statutes specifically providing that an individual in police custody cannot consent to sexual acts with a law enforcement officer.[181] Additionally, several other state legislatures proposed similar bills, indicating that the issue is gaining momentum in the other consent-defense states.[182]

In March 2018, New York state lawmakers passed a bill titled “An act to amend the penal law, in relation to establishing incapacity to consent when a person is under arrest, in detention or otherwise in actual custody.”[183] The legislation unanimously passed in light of Anna Doe’s case.[184] Additionally, fears of opposition from police unions and law enforcement community were quelled by the NYPD’s strong support of the bill.[185] The Mayor of New York City, Bill de Blasio, agreed that the loophole was “very troubling,” and the Governor of New York, Andrew Cuomo, said the legislation “closes an egregious loophole and helps protect against abuse in our justice system.”[186]

Introduced by Republican Senator Andrew Lanza with bipartisan sponsorship, the bill amended existing New York Penal Law in two different sections. First, the bill amended the definition of a person “deemed incapable of consent” to include an individual “detained or otherwise in the custody of a police officer, peace officer, or other law enforcement official . . . .”[187] Such an individual is incapable of consenting to sexual contact with “a police officer, peace officer or other law enforcement official who either (i) is detaining or maintaining custody of such person; or (ii) knows, or reasonably should know, that at the time of the offense, such person was detained or in custody.”[188] Second, the bill provides that it is a defense when the parties were married to each other.[189]

In May 2018, Kansas’ governor signed a similar bill closing the consent loophole,[190] but its scope exceeds even further than the New York bill. The Kansas bill amended the crime of unlawful sexual relations, which prohibits certain persons from engaging in “consensual sexual intercourse, lewd fondling or touching, or sodomy,” to include law enforcement officers when the person with whom they are engaging in such acts with is “a person 16 years of age or older who is interacting with such law enforcement officer during the course of a traffic stop, custodial interrogation, an interview in connection with an investigation, or while the law enforcement officer has such person detained.”[191] Such conduct is a level 5 person felony.[192]

Similar to New York law, the Kansas statute carves out an exception for situations in which the officer is married to the victim by stating unlawful sexual relations occur “with a person who is not married to the offender.”[193] However, unlike the New York law, the Kansas law defined police custody to include specific situations that protect not only detainees, but also witnesses, victims, and individuals involved in a traffic stop.[194] To illustrate how these two laws can result in different outcomes, reconsider the South Carolina case of Dereck Johnson.[195] Under Kansas law, officer Johnson would be guilty of unlawful sexual relations, regardless of consent, because he engaged in sexual conduct with a person he was “interview[ing] in connection with an investigation” of the reported domestic violence.[196] Conversely, under New York law, the victim would be potentially capable of consenting to sexual acts with Johnson because she arguably was not under arrest—or in police custody—at the time, therefore allowing Johnson to potentially claim the acts were consensual.[197]

The Louisiana Legislature unanimously passed[198] a bill providing that a person in police custody is incapable of giving consent.[199] The Louisiana statute resembles New York’s statute more than Kansas’s. The act adds a new subpart that provides for purposes of the crimes of rape and sexual battery, “a person is deemed incapable of consent when the person is under arrest or otherwise in the actual custody of a police officer or other law enforcement official,” and when the other party is the police officer or law enforcement official responsible for their arrest or for “maintaining the person in actual custody,” or “knows or reasonably should know that the person is under arrest or otherwise in actual custody.[200]

This act is very similar to the one passed by New York. Both require the individual to be under arrest or otherwise in actual legal custody and further provide that the offending officer be the arresting officer or otherwise have authority over or knowledge of the person’s custody.[201] Like New York, this statute potentially fails to protect witnesses and victims who may fall vulnerable to police sexual misconduct—but are not covered by the statute’s definition of police custody. Furthermore, unlike both the Kansas and New York statutes, Louisiana does not include the availability of a marital exception.[202]

Also, in May 2018, Maryland unanimously passed a bill that states that “a law enforcement officer may not engage in sexual contact, vaginal intercourse, or a sexual act with a person in the custody of the enforcement officer.”[203] Unlike the other state statutes previously discussed, the Maryland law does not explicitly state that such conduct is not consensual.[204] Nonetheless, Baltimore Delegate Brooke Lierman, the Democrat who proposed the bill, assured that “[i]f police officers try to argue the sex was consensual, the new law will make it clear the conduct is still illegal . . . ‘Because you’re in custody, you can never give consent,’ Lierman said.”[205]

The main difference in Maryland’s statute is the penalty associated with such misconduct. “In most states with statutes specifically addressing sex in police custody, the crime is categorized as sexual assault or sexual battery, felonies that bring at least a few years in prison at a minimum.”[206] The bill in Maryland, however, classifies the offense as a misdemeanor, “subject to imprisonment not exceeding 3 years or a fine not exceeding $3,000 or both.”[207]

New Hampshire passed a bill in June 2018 to close the consent loophole present in their law.[208] The act defined “aggravated felonious sexual assault” to include when the actor has “authority authorized by law over,” or is directly responsible for “maintaining detention of,” the victim who is “detained” or otherwise “not free to leave.”[209] The statute explicitly states that consent of the victim under these circumstances is not a defense.[210] The statute, however, includes only the act of “sexual penetration” in its definition of aggravated felonious sexual assault and further states that the actor use his position of authority over the victim “[to] coerce the victim to submit.”[211] This language makes New Hampshire’s statute narrower than the other states to close the loophole, and it also suggests the prosecutor has the added burden of proving the use of coercion.[212] Additionally, instead of providing marriage as a defense to such conviction, New Hampshire law states that upon proof that the parties were “intimate partners or family or household members,” the conviction is recorded as “aggravated felonious sexual assault-domestic violence.”[213]

In 2018, federal bills to close the consent loophole in the context of federal law enforcement officers were introduced in both the House and the Senate but failed to be enacted before the close of the 115th Congressional Session.[214] Nonetheless, the “Closing the Law Enforcement Consent Loophole Act of 2018” was met with support and the federal government should reintroduce the bill to be enacted in the current Congressional Session.[215]

Representative Jackie Speier introduced the House bill, “Closing the Law Enforcement Consent Loophole Act of 2018,” which would amend title 18 of the United States Code to make it a “criminal offense for Federal law enforcement officers to engage in sexual acts with individuals in their custody,” and “to encourage States to adopt similar laws.”[216] The bill would prohibit Federal law enforcement officers from engaging in sexual acts with an individual who is under arrest, detained, or otherwise in custody, regardless of that individual’s consent.[217] Punishment for such an offense would be a fine and/or a maximum term of imprisonment of fifteen years.[218]

A nearly identical Senate bill was later introduced by Senator Richard Blumenthal and Senator Cory Booker.[219] The main difference between the Senate and the House bill is the Senate bill’s inclusion of the phrase “acting under color of law.”[220] Thus, the proposed law, in general, would prohibit individuals “acting under color of law, [from] knowingly engag[ing] in a sexual act with an individual . . . in the actual custody of any Federal law enforcement officer,” and would expressly prohibit consent as a defense.[221] Furthermore, the bill would incentivize states to adopt similar laws and facilitate in the collection of data on reports of law enforcement officers engaging in sexual acts with individuals in the custody of law enforcement, by providing funding to states that do so.[222]

Even though the “Closing the Law Enforcement Consent Loophole Act of 2018” was not enacted, it is further evidence that the issue is gaining momentum and encourages those states which have not closed the consent loophole to take action as well.[223]

South Carolina is among the twenty-eight states that still have the presence of the consent loophole.[224] As such, the state of South Carolina should pass a bill providing that people in police custody are legally incapable of consenting to sexual acts with law enforcement officers.

Anna Doe’s case prompted South Carolina State Representative Mandy Powell Norrell to introduce a bill to amend Section 44-23-1150 of South Carolina Code of Laws.[225] The “Detainee Consent Bill” was introduced in the House during the 2019 to 2020 Legislative Session.[226] “The bill is based on the belief that crime suspects and victims should be given the same protection as inmates.”[227] Therefore, the Detainee Consent Bill would close the consent loophole and affirmatively recognize that individuals in police custody are incapable of giving consent to sexual encounters with police officers and other law enforcement officials.[228]

The Detainee Consent Bill would amend the current section of South Carolina law that defines the crime of “Sexual misconduct with an inmate, patient, or offender.”[229] First, the bill would amend the meaning of “actor” and classify it into three sub-parts.[230] Part (a) and part (b) come directly from the current statutory meaning of “actor.”[231] Part (c) is new matter that would be added to the meaning of actor: “a police officer or other law enforcement official,” who is responsible for either the arrest of the victim or “for maintaining the victim in actual custody,” or who “knows or reasonably should know that the victim is under arrest or otherwise in actual custody.”[232] This definition is comparable the ones found in the New York, Louisiana, and New Hampshire statutes, suggesting it is a sufficient change to the meaning of “actor.”[233] However, as noted in the comparison between the New York and Kansas bills, this definition of “actor” potentially would not extend to protect victims, witnesses, or suspects that are not arrested or “otherwise in actual custody.”[234]

Next, the Detainee Consent Bill would amend the meaning of “victim” to include “a person who is under arrest or otherwise in the actual custody of a police officer or other law enforcement official.”[235] Like the definition of “actor,” this meaning would restrict “victim” to only those arrested or otherwise in actual police custody. Additionally, the proposed bill does not explicitly include an individual that is “in detention,” although several other state statutes explicitly provide this.[236]

The bill would also provide that “a victim is not capable of providing consent for sexual intercourse or sexual contact with an actor.”[237] Importantly, the bill would cover both sexual intercourse and sexual contact; the definition of “sexual misconduct” would include when an actor knows the victim is a “person under arrest or otherwise in actual custody,” and, nonetheless, “voluntarily engages in sexual intercourse” or “other sexual contact” with the victim.[238] In contrast to the New Hampshire statute, this would allow citizens more protection from various forms of police sexual misconduct. Furthermore, unlike several states that have closed the loophole, the Detainee Consent Bill would not provide a spousal exception.[239]

If the Detainee Consent Bill had been enacted prior to the Dereck Johnson case, a different result might have occurred. First, in order for the bill to apply, the court must consider whether or not the victim was “in the actual custody” of a law enforcement official.[240] To determine whether an individual is in custody, “the trial court must examine the totality of the circumstances, which include factors such as the place, purpose, and length of the interrogation, as well as whether the suspect was free to leave the place of questioning.”[241] “The custodial determination is an objective analysis based on whether a reasonable person would have concluded that he was in police custody.”[242] Applying the Johnson case, this analysis would require more facts about the circumstances of Johnson’s interaction with the victim, but it also illustrates the potential shortfall in the bill’s protection of witnesses, suspects, and other individuals that come into official contact with on-duty police officers.

While the Detainee Consent Bill may not have led to the conviction of Johnson for sexual misconduct, it could potentially prevent incidences like this from happening in the first place. By officially criminalizing sexual acts between a police officer and an individual in police custody, the proposed bill may lead police departments to be more conscious of such conduct and increase training on the issue. In Johnson’s case, this could have prevented the argument that it was not included in the training manual and thus he did not know what to do in this particular scenario.[243] Furthermore, the availability of criminal prosecution for such acts could have alleviated the victim’s desire to file civil actions against Johnson and the Orangeburg County Sheriff’s Office.[244]

Passing the bill to close the consent loophole is a step in the right direction towards addressing police sexual misconduct. However, the lack of formal policies, recording systems, and research suggest that more needs to be done. “Perhaps, formal policies addressing [police sexual misconduct] will be developed and become standard in policing only when law enforcement is pressured by the public, the media, and the courts to enact such policies.”[245] The several cases within South Carolina that achieved media coverage were able to initiate some dialogue in the general public, but the lack of criminal punishment for the perpetrators suggests the system itself is flawed.[246] Enacting legislation to better protect individuals against police sexual misconduct is the first step towards ensuring that victims do not go without remedies and perpetrators are held accountable.[247]

Additionally, South Carolina must develop a uniform system of investigating and reporting police sexual misconduct, namely, independent investigations of allegations—as opposed to internal investigations by police unions.[248] Civilian oversight of such agencies could help ensure that investigations are done free from political and social influencers.[249] After all, “[t]he propriety of the investigation is less likely to be questioned when an outside investigative agency is involved.”[250] Furthermore, allegations of police sexual misconduct should be promptly investigated.[251] This will help avoid the high-dollar law suit settlements resulting from ignored allegations and insufficient investigations.

Finally, South Carolina police departments need to restructure their police handbooks and policies in order to properly educate officers about restrictions on sexual interactions with those individuals they encounter while on duty. In fact, most police departments do not have policies or training in place which explicitly state that on-duty sexual misconduct against civilians is prohibited.[252] Indeed, formal written policies are the dominate approach in controlling police behaviors, and “[t]here is little doubt that written policies specifically addressing sexual misconduct would help to establish a better understanding of this issue.”[253] Scholars agree that new policies and training programs within police departments are needed to address police sexual misconduct.[254] “Creating and implementing a policy are key steps to ensure an agency is prepared to respond to allegations, reinforce officer accountability, and ultimately prevent abuses of power.”[255]

The significant majority of police officers serve honorably, but the few who engage in sexual misconduct with individuals—many under their direct custody—while on duty have an outsized impact. The costs of passing South Carolina’s Detainee Consent Bill are marginal, especially considering the potential benefits of deterring, enforcing, and punishing police sexual misconduct with individuals in police custody.[256] Research reveals that sexual misconduct by officers is a problem facing law enforcement agencies across the country, and South Carolina is not immune from these difficulties.[257]

By allowing police officers to use the consent defense, the State of South Carolina is ignoring the power disparity between a police officer and an individual in police custody which renders consent problematic—at best. South Carolina law currently recognizes that an inmate is not capable of providing consent for sexual conduct with law enforcement officers[258] and the same protection should apply to individuals in police custody. The egregious consequences of the consent loophole were brought to light by the Dereck Johnson and Anna Doe cases, and a variety of factors explain why a crime suspect—or victim—is unable to consent to sexual acts with a law enforcement officer while in custody. The State of South Carolina should follow the example of other states that have closed the loophole and pass a law to provide individuals in police custody the same protection as inmates.

Figure 1: States Prohibiting Police and Detainee Sexual Conduct Regardless of Consent[259]

2_story.html?utm_term=.c1aea118bff9 (“Police officers wield significant power and discretion, and are protected by a blue wall of silence when they abuse them.”); Rabe-Hemp & Braithwaite, supra note 25, at 129 (stating that state laws keep police internal investigations from the public and noting the “hidden nature” of police sexual misconduct). ↑