The Youth Tax in Parole Hearings

By

By

David M. N. Garavito,[1]* & Amelia C. Hritz ,[2]** & John H. Blume[3]***

In recent decades, the Supreme Court has made clear that the differences between adults and juveniles necessitate treating youth as a mitigating—and not an aggravating—factor in sentencing. In these decisions, the Court relied on an abundance of research finding that juveniles and emerging adults are less culpable, more prone to positive change, and more susceptible to rehabilitation compared to their adult counterparts. The Court concluded that categorical bans on the death penalty and mandatory life without parole sentences for juveniles were necessary because, inter alia, youth may be improperly treated as an aggravating factor because qualities that make youth less culpable, such as diminished impulse control and increased susceptibility to peer influence, may also make them appear to be more dangerous to juries. The same may be true for parole boards, but few cases or research studies have directly examined the treatment of adolescents versus adults in parole hearing outcomes, arguably the step in the criminal justice system that most relies on perceptions of growth and positive change. In this study, we obtained data for all parole hearings in South Carolina from 2006 to 2016 (n = 43,290). This data included information regarding convictions, parole hearings, and demographic variables. Of our total, 9,605 parole hearings involved people who were incarcerated for crimes committed before they turned twenty-one. Using propensity score matching, we matched every parole hearing involving a youthful offender with one involving a comparable adult who was similar or identical on the number of violent and non-violent felonies, time served, race, sex, any subsequent conviction after incarceration, number of life sentences, number of murder convictions, and the year the hearing took place. Using this method, we were able to obtain a balanced comparison, similar to an experimental design, to isolate the effect of youth on parole hearing outcomes. We then used a logistic regression to predict parole hearing outcomes while controlling for our variables of interest. Our results showed that the parole board was significantly less likely to grant parole to a “youthful offender” compared to an adult when controlling for all other variables: “youthful offenders” were about 20% less likely to be granted parole compared to adults. This effect was robust when further narrowing to parole hearings involving people who were incarcerated for crimes committed before they turned eighteen (i.e., juvenile offenders; n = 1,633). This research suggests the existence of a “youth tax” in parole hearings, whereby people convicted of crimes when they were emerging adults or juveniles are punished more harshly compared to adults. This finding is deeply concerning given the Supreme Court’s clear mandate that youth are less culpable for their actions and more amenable to change compared to adults and the research that those rulings were based on.

Stewart Buchanan, the longest serving juvenile offender in the South Carolina Department of Corrections, appeared before the Parole Board in 2018, assisted by pro bono counsel and law students.[4] Prior to the hearing, he had submitted a memorandum to the Board that provided a detailed summary of his crime, the risk factors that led to it, and his lifetime of growth, progress and rehabilitation during his forty-five years of incarceration.[5] The materials presented to the Board described his dysfunctional and chaotic childhood, where he experienced and witnessed physical and emotion abuse and abandonment.[6] Like many children raised in similar environments, he started using substances at a young age.[7] At age seventeen, and under the influence of alcohol, LSD, and sleep deprivation, he broke into a neighbor’s home.[8] She fled, but Buchanan chased her down and stabbed her to death.[9] When later questioned by the police, he admitted that he committed the act, “tak[ing] full responsibility for his actions and the consequences thereof.”[10] Buchanan’s attorney knew that his client would be eligible for parole after ten years if convicted of murder and that at the time it was very rare for someone to be incarcerated for more than twenty years.[11] With these assurances from his attorney, Buchanan pled guilty and was sentenced to life imprisonment with the opportunity for parole after ten years.[12] At his sentencing, the trial judge told Buchanan that his crime was the result of a “‘tragic situation’ and expressed his hope that Stewart could ‘salvage some phase of his life.’”[13]

Throughout his incarceration, Buchanan worked to better himself and to prepare himself to reenter society. Still seventeen, he visited schools and churches to warn other teenagers of the dangers of substance use.[14] Later, he became a certified tutor, teaching English and even basic legal research and writing.[15] Back when the South Carolina Department of Corrections allowed inmates to work “outside the walls” at designated facilities and businesses, Stewart did so for many years successfully and without incident. Buchanan also volunteered for many other roles at the various institutions in which he was incarcerated; he served as an Inmate Grievance Clerk, a hospice volunteer, and a member of an official rehabilitation-focused group.[16] To ensure that he could volunteer for such positions, Buchanan also had to maintain an exemplary disciplinary record.[17] Switching his attention to potential post-release work, Buchanan started working with a release plan program organized by a Christian-based organization.[18] He took hundreds of hours of classes, worked as a manager, and was given the organization’s highest recommendation.[19] That recommendation guaranteed him mentorship and additional training after release, as well as two years of transitional housing and assistance finding a job and buying a home.[20]

Despite this long proven track record of rehabilitation, and despite recommendations from employers, mentors, and a clinical psychologist who opined, among other things, that he was a (very) low risk to reoffend, Buchanan’s application for parole was denied.[21] This result was not new to Buchanan; his requests for release had been repeatedly rejected by the parole board since his first hearing on January 12, 1983.[22] The summary denial letter he received indicated he was denied parole based on the following criteria: “(1) the nature and seriousness of the offense; (2) an indication of violence in this or a previous offense; and (3) the use of a deadly weapon in this or a previous offense.”[23] As should be clear to the reader, these were all things that, despite his nearly fifty years of growth and effort, he could (and can) never change. Buchanan, seemingly, is going to remain in prison for life due to a drug-addled, impulsive crime he committed when he was still a teenager.

When social justice and policy reform groups examine areas of the criminal justice system that need improvement, the focus typically centers on earlier stages of the criminal justice system such as policing, prosecutorial charging practices, plea bargaining and sentencing. Academics, in turn, who often conduct the empirical research that groups rely on, also overwhelmingly focus their research on these same aspects of the criminal justice system.[24] Relatively little attention has been paid to parole systems, despite the fact that, after a person has been arrested, convicted, sentenced, and has exhausted all appeals (if pursued), for many prisoners the only mechanisms for release are commutations, pardons, and, most importantly and the subject of this article, parole. In fact, in 2021, almost 1 million adults in the United States were on parole,[25] and, in South Carolina, the state that this article focuses on, at least a few hundred people are paroled each year.[26] Accordingly, the blind spot in research and attention on parole is critical and should be addressed. We hope to provide some evidence in this Article to help fill that gap.

Parole is a legal process where incarcerated people may be released from imprisonment before the end of their sentence (their determined period of incarceration).[27] Unlike probation, which is a period of supervision imposed in place of imprisonment, and commutation, where a sentence is shortened via an order from the head of the government, people “out on parole” are simply serving their sentences of incarceration outside of a prison environment.[28] Additionally, parole is conditional and can be revoked, depending on the applicable laws of the jurisdiction.[29] There are several types of parole systems that exist in the United States. Historically the most common system, and the subject of this Article, is discretionary parole, where a board of people vote, at their discretion, on whether a person deserves to leave incarceration.[30] In contrast, many states and the federal government have a determinant sentencing scheme and presumptive parole—a system that allows for the automatic early release of an inmate after serving a set proportion of the sentence given the satisfaction of certain conditions, such as a good behavior.[31] Determinant sentencing schemes became popular in the latter half of the twentieth century, when politicians on both sides of the political spectrum became critical of discretionary parole systems.[32] Some criticized discretionary systems because of fears that non-rehabilitated people would be released arbitrarily.[33] Others criticized the discretionary systems because of concerns that people of color and other oppressed groups might be arbitrarily denied parole.[34] Nevertheless, many states, such as South Carolina, continue to use a discretionary parole system.[35] Also, among states with discretionary parole systems, the particular processes and the criteria that individual states and their parole boards set for people applying for parole differ.[36]

In this Article, we used data from the South Carolina Department of Probation, Parole and Pardon Services on all parole hearings from the years 2006 to 2016. With these data, we examined the effects of a person’s status as a youthful offender on parole hearing outcomes. Our results show that the parole board penalized those who committed crimes when they were younger. While controlling for other important characteristics, parole boards were significantly less likely to parole youthful offenders compared to others. There is, in sum, as the title of this article indicates, a “youth tax.” This finding stands in stark contrast to public opinion and the opinions of the Supreme Court over the past decades. Regarding the former, multiple surveys over several decades have found that the public generally views youthful, particularly juvenile offenders, as less culpable and deserving of more lenient punishments compared to older, adult offenders. Similarly, the Supreme Court, considering research on both public opinion and human development, has held that the hallmark characteristics of youth lessen culpability to a significant degree and warrant additional protections for juvenile offenders. Specifically, the Supreme Court has highlighted the need for juveniles to have a “meaningful opportunity to obtain release.”[37] This apparent disconnect between the reality of parole hearings and the views of the public and the Supreme Court merits concern.

This Article proceeds in four parts. In the first part, we provide background on the parole system in South Carolina, a rare state that gives its parole board extraordinary power and discretion. In the second part, we provide brief primers on those characteristics of youth that affect the perceptions of both the risk that adolescents and emerging adults (ages eighteen to twenty-one)[38] pose to society and the (diminished) culpability of those same age groups with regards to criminal acts. We conclude by summarizing legislative and judicial shifts with regards to the treatment of juveniles compared to adults. In the third part, we describe our hypothesis, our data, and the analyses we performed to test our hypothesis. We also describe propensity score matching (PSM), a method of matching people from different groups to simulate an experimental design and strengthen the interpretation of the results. Here, we were able to divide our sample into youthful (twenty-one and younger) offenders and others and use PSM to match each youthful offender to a similar adult. Our results, which are described in the fourth part, show that parole boards are 20% less likely to grant parole to youthful offenders compared to adults. This was true even when controlling for variables such as the number of non-violent and violent felonies, whether the person was convicted of a subsequent crime while serving the original sentence, etc. We also ran supplemental analyses comparing juvenile (eighteen and younger) offenders to adults, which replicated the earlier effects. Finally, in the fifth part, we interpret our results within the context of previous research and draw several conclusions.

We begin with an overview of South Carolina’s parole system. South Carolina’s Board of Paroles and Pardons, which is part of the Department of Probation, Parole and Pardon Services (DPPPS), oversees all decisions regarding paroles and pardons in the state.[39] The Board also makes recommendations to the governor regarding commutations.[40] In South Carolina, the Board is composed of seven members, one from each congressional district in the state, appointed to six-year terms.[41] Terms are staggered, and members can be reappointed.[42] There are few qualifications for membership or rules regarding the makeup of the Board. For example, members of the Board tend to have some experience in law or criminal justice,[43] though South Carolina law merely demands that one member of the Board has a minimum of five years of experience (work or volunteer) in a field such as criminal justice, law enforcement, social work, or psychology.[44]

South Carolina’s parole system is particularly compelling to study because of the extremely broad discretion the Board possesses, as well as the relative lack of legislative and judicial oversight.[45] Specifically, the Board, given that it is part of DPPPS, operates completely separately from the South Carolina Department of Corrections (SCDC).[46] This structure is not common and gives the Board exceptional operational independence; however, the structure also results in large mismatches between the objectives and incentives of the two administrative bodies.[47] Compared to the SCDC, for example, the DPPPS is less involved with people who are incarcerated and, obviously, would be the subjects of the eventual parole hearings. Further, the consequences of denying parole for a person are not evenly shared by the Board and the SCDC; failure of SCDC programming to result in parole release and the costs incurred by incarceration are not a factor in the Board’s decision making.[48]

Regarding the actual parole process in South Carolina, a person must serve a pre-determined proportion of the sentence before becoming eligible to apply for parole.[49] The particular proportion required depends on the type of crime committed (i.e., violent or non-violent) and, in some cases, the nature of existing sentencing structure at the time.[50] Up to ninety days before the person serves the required proportion of the sentence, DPPPS reviews the case to confirm that all criteria for parole eligibility have been met.[51] At this same time, if the person is confirmed to satisfy all necessary criteria for parole eligibility, DPPPS will assign a parole examiner who is tasked with creating the parole case summary report. The report includes information relevant to the Board’s parole criteria including a description of the offense, records from SCDC (disciplinary records, participation in programming, etc.), the output of a risk assessment tool (typically the COMPAS),[52] other records “before, during, and after [the person’s] imprisonment,” the individual’s plan for housing and employment should they be released, and the parole examiner’s opinion on the person’s suitability for parole.[53] South Carolina is not a state that allows for presumptive parole; there are no criteria that a person can fulfill that will automatically merit release.[54]

All hearing dates are scheduled thirty days in advance,[55] with the Board hearing up to sixty-five cases per day.[56] Three weeks prior to their hearings, those people seeking parole are required to submit all requested materials to the Board. The Board combines the person’s materials with the parole case summary report.[57] Additionally, South Carolina requests input from those connected to the potential parolee’s original conviction, specifically any surviving victims and the original prosecutor.[58] Notably, however, input in support of the potential parolee from family members, SCDC staff, or past or future employers is only allowed at the discretion of the Board.[59] The resulting collection of documents serves as the final official parole record, and it is the sole responsibility of the person seeking parole to identify and correct any mistakes in the record. Nevertheless, confusingly, the Board is highly restrictive of potential parolees and their attorneys (if they can afford one) concerning access to the official parole record, even to the information or documents that they cannot access in any other way (e.g., the COMPAS report).[60] The Board justifies its opacity by stating that “all information obtained by probation and parole agents in the discharge of their official duties is privileged information.”[61] As such, under the guise of protecting the views of their agents, the Board severely limits access to the official record, absent a court order.[62]

The tremendous amount of power and discretion afforded to the Board is not limited to what material is included in, and who is allowed to view, the parole record. To start, South Carolina law provides a few required determinations when the Board decides whether to grant parole.[63] In order to justify granting parole, the Board must conclude that:

that the prisoner has shown a disposition to reform; that in the future he will probably obey the law and lead a correct life; that by his conduct he has merited a lessening of the rigors of his imprisonment; that the interest of society will not be impaired thereby; and that suitable employment has been secured for him.[64]

Outside of these statutory requirements, there are no restrictions on how the Board goes about determining individual cases. There are no statutory criteria for the Board to follow,[65] and, in fact, the relevant statute authorizes the Board to create their own decision-making criteria.[66] In these criteria, as well as the language from the Board’s manual, the Board seemingly focuses on a few key characteristics: a risk assessment of the person, the circumstances and impacts of the current offense, criminal history, culpability, and any signs of growth or rehabilitation.[67] The exact criteria listed in the Board’s manual have remained relatively unchanged over time and are currently listed as such:

[t]he risk that the offender poses to the community; [t]he nature and seriousness of the offender’s offense, the circumstances surrounding that offense, and the prisoner’s attitude toward it; [t]he offender’s prior criminal record and adjustment under any previous programs of supervision; [t]he offender’s attitude toward family members, the victim, and authority in general; [t]he offender’s adjustment while in confinement . . . ; [t]he offender’s employment history . . . ; [t]he offender’s physical, mental, and emotional health; [t]he offender’s understanding of the causes of his past criminal conduct; the offender’s efforts to solve his problems; [t]he adequacy of the offender’s overall parole plan . . . ; [t]he willingness of the community into which the offender will be paroled to receive that offender; [t]he willingness of the offender’s family to allow the offender, if he is paroled, to return to the family circle; the opinion of the sentencing judge, the solicitor, and local law enforcement on the offender’s parole; [t]he feelings of the victim or the victim’s family, about the offender’s release; [a]ny other factors that the Board may consider relevant, including the recommendation of the parole examiner.[68]

Such criteria are commonly considered by parole granting institutions.[69] In a survey published by the Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice, when tasked to rank the importance of factors, parole board chairpersons ranked the “static” variables (such as the circumstances of the offense and criminal record) as most important, followed by variables related to risk and rehabilitation (e.g., a risk assessment, participation in programming, etc.).[70] Variables related to outside opinions, such as those by the person’s family, were considered least important.[71] Nevertheless, in addition to listing these criteria, the Board also provides a disclaimer in its manual that it is not bound to the listed criteria: “The publishing of these criteria in no way binds the Board to grant a parole in any given case.”[72] The tremendous amount of discretion afforded to the Board, combined with the extraordinary opacity throughout the parole process, can prove frustrating for any applicant and advocate going through the process.[73]

The parole hearings are often only a few minutes long since, as noted, the Board hears up to sixty-five cases in one day. In the past, the Board would provide their decision during the hearing. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, however, at the hearing, the Board now provides no indication of their decision, nor a justification. Instead, the potential parolee must wait, incarcerated and in limbo, for an extended period of time until the Board sends a written notice of its final decision.

If a person is lucky, then the Board will have voted to grant them (conditional) parole. The number of votes needed for the Board to vote in favor of parole depends on whether the person was convicted of a violent or non-violent offense. For cases involving only non-violent offenses, all members of a three-member panel of the Board must vote in favor of parole.[74] In cases involving violent offenses, at least two-thirds of a quorum of the full Board must vote in favor of parole.[75] An overall vote in favor of parole is not the end of the process, however. Before release, South Carolina law mandates that all those released on parole must agree to a warrantless search of their person, any vehicle they own or operate, and all their personal possessions.[76] Additionally, South Carolina requires parolees to participate in a risk assessment. Even if the results of the search would yield nothing illicit, failure to submit to the search would prevent the person from being released on parole. The same is true if the results of the risk assessment tool are sub-optimal to whatever degree the Board deems significant. Of course, it is important to note that a significant portion of incarcerated people in South Carolina rarely make it to this point in the parole process. For others, they must deal with rejection and all that follows.

If, after the long wait period following the hearing, a potential parolee receives a written denial from the Board, that person will receive little additional information. The one-page, summary sheet simply includes a list of reasons for denial, chosen from six possible options.[77] Importantly, four of the six reasons for denial concern things that are not possible to mitigate or correct. Officially, a person may be denied parole for one of the following reasons: (1) “Nature and seriousness of the current offense;” (2) “Indication of violence in this or a previous offense;” (3) “Use of a deadly weapon in this or a previous offense;” (4) “Prior criminal record indicates poor community adjustment;” (5) “Failure to successfully complete a community supervision program;” and (6) “Institutional record is unfavorable.”[78] Denial for reasons other than institutional record or failure to complete programming is counterintuitive to the purpose of discretionary parole: demonstrating that one is reformed. Such denials also highlight the aforementioned disconnect between SCDC, who may be incentivized to release individuals to prove efficacy of institutional programming, and DPPPS, who has different incentives and does not share the institutional costs of continued incarceration.

The vague reasons given for denial of parole, and the lack of any additional information, also hinders the construction of viable appeals challenging the Board’s decision-making process. Nevertheless, even if a person, with an attorney (if the person can afford one), is able to obtain enough information to create a viable appeal, the likelihood of success is still very low. This is primarily because most appeals fall under the umbrella of administrative law.[79] This difference is key for one particular reason: Under administrative law, the Board’s decision is reviewed based on the arbitrary and capricious standard.[80] In other words, the respective court would presume that the Board followed the law and guidelines governing it, and the appellant would have the burden of proof to show that the Board decided, instead, in a way that did not follow the respective laws and guidelines and the decision was solely based on its own free will.[81] Given that there is little statutory oversight, that the Board does not bind itself to the criteria that it makes for itself, and the opacity and other roadblocks preventing those interested from obtaining relevant information, the chance of a successful appeal is miniscule.[82]

Virtually all persons denied parole are required to wait one or two years until their next parole hearing for another chance at release. Given the challenges faced by potential parolees and their advocates, policy groups like the Prison Policy Initiative have strongly criticized South Carolina’s parole system.[83] Nevertheless, despite its shortcomings, there are a few positive features of South Carolina’s system. Several states, for example New York, prohibit the presence of an attorney during parole hearings.[84] Of course, given that many incarcerated people often lack the funds necessary to hire attorneys, allowing an attorney may not be a substantial improvement over the discretionary parole systems in these other states. South Carolina’s system also makes it a unique environment to study the potential impact of youth in criminal contexts. Particularly given that potential parolees could be indefinitely denied parole based on the circumstances of their original offense(s), youthful or juvenile offenders could be punished indefinitely for mistakes made when they were young. Stewart Buchanan, as mentioned in our Introduction, is, perhaps, the perfect example of such a scenario. Given the research on decision making across the lifespan, and the Supreme Court of the United States’ decisions regarding juveniles in criminal contexts, one can start to understand the true dangers of a parole system like South Carolina’s.

The treatment of juveniles in the criminal justice system has, for the most part, evolved in tandem with our understanding of human development and adolescent decision making. For example, as it has become more apparent that minors, particularly adolescents, are more impulsive and susceptible to the pressure of peers, the Supreme Court has considered that research in holding that, as a group, juveniles are less culpable compared to identical adults. In this section, we juxtapose these two aspects of youth. We begin by giving a brief primer on how youth can be perceived as a risk factor. Much of the attention on youth in the criminal justice system has been within conversations about culpability. However, these characteristics that children possess which make them less culpable are the same ones that make youth a risk factor for criminal behavior.[85] Specifically, we discuss how changes in decision-making and risk-taking increase the likelihood of hazardous behaviors, such as criminal activity. We contrast this discussion of increased risk with a subsequent discussion of culpability. Specifically, how does youth alter the perceptions of culpability with regards to criminal behavior? Lastly, we shift the focus from the public perception of culpability to the rules and policies established by courts and legislatures regarding the treatment of youthful defendants. In this section, we discuss the laws that allow children to be tried as adults and we review judicial decisions regarding the treatment of children, as well as the reasoning behind those decisions.

Beginning in adolescence, arrests rates for various crimes steeply rise, often peaking in early adulthood.[86] The exact peak depends on the particular type of crime.[87] The age with the highest rates of arrest for property crimes (e.g., burglary, theft, arson) is around eighteen years old. The peak for violent crimes (e.g., homicide, robbery, aggravated assault) occurs in the twenty-one to twenty-nine age group, though the eighteen to twenty age group also has a high average arrest rate for violent crimes.[88] After thirty years of age, arrests for all crimes generally tend to decline.[89] Likely based on these crime rate data, many risk assessment tools used by state and local governments, such as the COMPAS, consider youth as a factor that increases the potential danger a person may pose to society. [90]

It should be noted that a significant portion of this research does not abide by the traditional “cutoff” for distinguishing adolescents from fully-fledged adults (i.e., eighteen years of age). Instead, many of those in the fields of developmental psychology and human development have acknowledged that the differences between, for example, a middle-aged adult and a sixteen-year-old would likely also be seen between that same adult and an eighteen-year-old. Further, some forms of risky decision making, such as committing criminal acts, peak between the ages of eighteen and twenty-one.[91] As such, many researchers have defined other non-adult age groups, such as early adults (eighteen to twenty-one),[92] in their research or otherwise accounted for the relative arbitrariness of setting eighteen as a cutoff. Although arbitrary cutoffs are sometimes unavoidable in law, research has generally shifted away from distinguishing, for example, traditional juveniles and those who are youthful but not under eighteen (e.g., twenty years of age).

A possible explanation for the increase in violence and criminal behavior in adolescence and early adulthood compared to other stages of life is the propensity toward impulsivity. Impulsive and risk-seeking behavior peaks in adolescence and declines over time.[93] There are many mechanisms that have been theorized to cause such a trend.[94] The most well-known is the so-called neurodevelopmental imbalance model.[95] This model posits that, because different areas of the brain develop at different rates, there is a risk of a developmental imbalance.[96] Specifically, the pre-frontal cortex, an area associated with decision-making, monitoring, and inhibition, takes longer to develop compared to emotional and reward-focused areas such as the limbic system.[97] The resulting imbalance, which supposedly peaks during adolescence, pits fully-developed reward processing against under-developed inhibition.[98] This theory, and others, is closely related to default-interventionist theories of decision-making, the most popular of which is, arguably, Daniel Kahneman’s Type I and Type II.[99] These theories generally state that people use primitive, impulsive, and fast decision making as a default and that slower “rational” deliberation intervenes only when possible and necessary, resulting in phenomena such as cognitive biases.[100] This theoretical framework generally dominates most popular understandings of decision making, though modern theorists have since expanded on these earlier approaches.[101] Nevertheless, the biological component of the neurodevelopmental imbalance mechanism for adolescent risk taking is certainly compelling because it implies that younger age groups may be, to at least some measurable degree, biologically unable to conform their behavior to the standards set for adults.

Another factor relevant to the association between youth and anti-social decision-making is the increased influence of peers. The pressure that peers place on each other to engage in risky behavior, and the susceptibility of adolescents to such pressure, have been studied for decades.[102] Peer pressure among adolescents is well-documented and has been observed in multiple contexts, such as sexual risk taking[103] and substance use,[104] both of which are also correlated with criminal activity.[105] This type of peer influence can also spill over into criminal acts. It is not surprising that crimes committed by adolescents are more likely to involve other defendants.[106] Combined with the influence of impulsivity and the general predisposition towards anti-social behavior, such peer influences may lead to multiple juveniles being convicted of multiple felonies, including homicide. Seeking to better understand peer pressure, researchers have attempted to identify causes and have highlighted various domains where peer pressure might impact people differently across the lifespan.[107] Nevertheless, this characteristic of youth is another one that increases perceived risk that a person may pose to the public. Coincidentally, crimes involving multiple people also tend to be considered more heinous, which exacerbates the perceived risk of youth.

It is important to reiterate that susceptibility to all these risk factors decline with age, including susceptibility to peer pressure.[108] The influence of most, if not all, of these risk factors seems to significantly decline by the time a person reaches their mid-twenties.[109] These findings related to risk factors associated with age align with the findings showing that criminal activity significantly declines for all people after the age of 30.[110] Given these findings, it is unsurprising that researchers studying real-world parole hearing data have found that being older at the time of the parole hearing and being older at the time of eventual release are associated with greater likelihood of being granted parole.[111] The growth and increase in maturity that occurs between adolescence and adulthood, as we will discuss, inextricably tied to discussions about how youthful offenders should be treated in a just society.

As we have highlighted major differences in decision making between age groups, one question naturally arises: Given that some characteristics of youth are associated with reduced ability to control behavior and that there are higher rates of certain crimes among adolescents and young adults, do people generally view others as more or less culpable depending on their age? Research has shown that the public has viewed juveniles as less culpable compared to adults, but that view has not been consistent over time.[112] Near the end of the twentieth century, media outlets reported that violent crime rates for younger age groups were spiking compared to the same crimes committed by older age groups.[113] These alarming reports coincided with public anxiety about young “super predators” and resulted in a shift towards incarceration and away from rehabilitation for youthful offenders.[114] In recent years, those reports have generally been debunked as the result of sensationalist media.[115] Nevertheless, even during that period of increased societal fear of young “super predators,” the public generally still held less punitive views regarding juveniles who committed the same or similar crimes compared to adults.[116]

After crime rates dropped near the turn of the twenty-first century, public opinion started to, once again, shift away from retributive strategies for juveniles convicted of crimes.[117] This trend has generally remained stable[118] and has, at least in some part, been attributed to changes in the public’s perception regarding the culpability of youths. When considering the potential punishments for adolescents, people consider the nature of the specific offense, the age and maturity of the juvenile, and the different potential punishments that are available.[119] Generally, it can be said that the public’s views towards younger people convicted of crimes is more rehabilitative and situational compared to adults, at least with regards to sentencing.[120] Outside of particularly heinous crimes, like especially gruesome murders, research has also found that the public is more supportive of punishments involving little to no incarceration for juveniles.[121] Nevertheless, as mentioned earlier, the same influences that may make juveniles less culpable for committing crimes may also increase the likelihood of a crime committed by a juvenile being considered heinous.[122]

There is relatively little known about how those who are convicted as juveniles are treated when approaching the latter stages of the criminal justice system. Specifically, are those people who are convicted of crimes when they are juveniles treated differently compared to adults when going up for parole? In terms of experimental work, one fairly recent study randomly assigned people to act as parole board members in order to decide whether a juvenile offender was worthy of early release from incarceration.[123] The researchers varied the circumstances of the offense and the perceived risk of harming others post-release.[124] The authors found that risk assessment, but not the circumstances of the crime, were significantly associated with the final judgement of early release.[125] The results of that study highlight, again, the fear that youth, and exposure to criminal activity as a youth, increases the risk that a person poses to society. The results also highlight, however, the lack of importance placed on the original offense, likely due to the perceived diminished culpability of youths. Accordingly, it seems that the public is generally concerned with whether youthful offenders can demonstrate growth and change, as opposed to the circumstances of the original crime. Although reassuring, these findings conflict with the troublesome aspects of South Carolina’s parole system we discussed previously (i.e., reasons for denial primarily concerning the circumstances of the original offense).

When turning to studies examining similar hypotheses in real-world contexts, research using actual parole hearing data is incomplete. There is a dearth of work examining whether a person’s age at the time that the crime(s) was committed, or status as a youthful or juvenile offender, affects parole outcomes. Combining this with the fact that parole hearings are relatively understudied compared to other parts of the criminal justice system, this gap in knowledge suggests that there is considerable work that needs to be conducted in this area. Of the few existing studies, one using a sample of hearings from California found that being younger at the time of the offense was associated with a greater likelihood of parole;[126] however, in this study, the average age at the time of the crime was nearly twenty-six, and it is unclear how many people committed crimes under the age of twenty-one (let alone eighteen).[127] Perhaps most relevant to this Article, in a previous article using a small subset of this Article’s data,[128] Amelia Hritz compared juveniles and adults who were convicted of murder and sentenced to life without parole.[129] Here, she found that juveniles, although having a significantly higher parole rate compared to adults, were paroled at very low rates, especially when controlling for other relevant characteristics.[130] Further, differences between juvenile offenders and non-juvenile offenders (e.g., criminal records) complicated the interpretation of results.[131] Hritz also found that South Carolina seemed not to adapt to shifting views from the public nor from the Supreme Court, as we will discuss later, and juvenile offenders were routinely denied parole for reasons such as the seriousness of the offense, which, as mentioned earlier, are impossible to mitigate.[132] Given how the perception of juveniles has changed over time, how our understanding of juvenile behavior has changed, and the potential disconnect between law and the realities of human development, it is not surprising that, in the past few decades, the Supreme Court has stepped in to rectify potential injustices.

As public opinions regarding risk and culpability shifted over decades, it is not surprising that laws concerning the treatment of juveniles have also evolved. One major shift that happened during the fear of “super predators” was the increased ability and frequency of transferring juvenile offenders to adult criminal courts.[133] Generally, there are several key differences that make juvenile courts more favorable to adult criminal courts, including limits on punishment, greater involvement of the juvenile’s family, greater access to education and support services, the lack of criminal convictions, and the increased ability to expunge adjudications of delinquency (compared to adult criminal convictions) at a later time. Currently, in South Carolina, family courts have original jurisdiction over offenders who were under the age of eighteen at the time of committing their offense.[134] If a juvenile is tried and convicted in a family court, then the maximum sentence which can be assigned is an indeterminate sentence until the juvenile’s twenty-second birthday.[135] The juvenile will then be remanded to the Department of Juvenile Justice, which determines the appropriate environment for the juvenile.[136] No one under the age of eighteen can be sentenced to an adult correctional institution via a family court disposition.[137] There is no constitutional requirement for juvenile offenders to be tried and sentenced outside of criminal courts, and each state has its own policies regarding when a court is allowed to transfer juveniles to adult criminal courts.[138] In South Carolina, the minimum age that a child can be transferred to an adult criminal court is fourteen.[139] In addition to this age requirement, the juvenile must be charged with particular types of crimes before a family court judge is allowed to transfer the jurisdiction.[140] The younger the juvenile is, the more severe the crime(s) charged must be before a family court judge is allowed to transfer jurisdiction over the juvenile.[141] Assuming the criteria are met, the judge may, but is not required to, transfer the jurisdiction over the juvenile to the appropriate criminal court if the judge, after a full investigation and hearing, determines that remaining in family court is contrary to the best interests of the child or the public.[142] Individuals who are seventeen years old and charged with certain felonies are transferred automatically to criminal court, with an option for a remand to juvenile court.[143]

Once juveniles have been transferred to adult criminal courts and convicted, there remains the added difficulty of determining the appropriate sentence. In fact, over the past two decades, the Supreme Court of the United States has heard several cases concerning whether, and to what extent, youth should factor into sentencing. Perhaps the most significant recent case was Roper v. Simmons.[144] In that case, seventeen-year-old Christopher Simmons told two of his friends that he planned to commit a burglary and murder because he supposedly wanted to kill someone, and believed that he would get away with it, even if he was caught (because he was a minor).[145] Simmons and one of his friends broke into a home, kidnapped a woman, and murdered her by throwing her off a bridge while tied up and conscious.[146] After he was convicted for first-degree murder, the trial court imposed the death penalty.[147] The Missouri Supreme Court overturned the sentence, instead sentencing Simmons to life without parole, on the basis that sentencing a juvenile to the death penalty violated the Eighth Amendment.[148] The Supreme Court of the United States agreed, holding that the Eighth Amendment prohibited the use of capital punishment on juveniles.[149] In its decision, the Court relied on several different reasonings, such as the declining use of juvenile capital punishment across the nation,[150] evolving societal standards,[151] and the characteristics of youth.[152] Justice Kennedy, speaking for the majority, wrote that given the greater vulnerability to peer pressure and the underdeveloped traits and sense of responsibility “it would be misguided to equate the failings of a minor with those of an adult.”[153] To the Court, categorizing any juveniles as among those most culpable and deserving of execution, a necessity for the justification of the death penalty, was impossible.[154]

After Roper, two more cases appeared before the Court which highlighted the importance of parole for juveniles in the criminal justice system. The first case, Graham v. Florida,[155] involved a seventeen-year-old Terrance Graham.[156] Graham was sentenced to life in prison after being convicted of a home invasion, violating a plea agreement he made after being arrested for armed burglary with assault and battery less than a year earlier.[157] Florida had abolished parole at this time, so the conviction essentially resulted in a sentence of life without parole for Graham.[158] The Supreme Court held in favor of Graham; writing for the majority, Justice Kennedy once again relied on research distinguishing the social, emotional, and cognitive abilities of juveniles compared to adults.[159] To the Court, “criminal procedure laws that fail to take defendants’ youthfulness into account at all would be flawed.”[160] Citing research on impulsivity and susceptibility to social pressures, the Court stated that these characteristics of youth could lessen the effectiveness of representation, predispose one to crime, etc.[161] Further, the Court, highlighting how younger people are also more susceptible to growth and rehabilitation, held that, for nonhomicide crimes, states must offer some “meaningful opportunity to obtain release . . . .”[162] In this way, the Court argues, the criminal justice system should offer juveniles the opportunity to “demonstrate growth and maturity” later in life, the lack of which may have been one of the causes for the crime committed.[163] The Court did not address homicides, however, and left open the possibility that irredeemable juveniles convicted of heinous crimes may still be sentenced to life without parole.[164]

Two years later, the Court extended the reasoning from Graham to a new case involving the sentencing of juveniles: Miller v. Alabama.[165] Miller was a fourteen-year-old boy who was tried as an adult and convicted of “murder in the course of arson.”[166] That crime, in the state of Alabama, came with a mandatory sentence of life without parole.[167] The Supreme Court, in holding that applying the mandatory scheme to juveniles was unconstitutional, stated that “mandatory penalties, by their nature, preclude a sentencer from taking account of an offender’s age and the wealth of characteristics and circumstances attendant to it.”[168] The Court, citing both Roper and Graham, further criticized criminal procedures that do not ensure consideration of age, such as mandatory sentencing schemes.[169] According to the Court, those procedures, by their nature, run the risk of disproportionately punishing the youth because the same characteristics that predispose the person to the crime, and make the person less culpable, are not being considered at the stage where culpability and potential for growth are most relevant.[170]

Relevant to this Article, two years after Miller, the Supreme Court of South Carolina further built on this line of cases in Aiken v. Byars.[171] In Aiken, the petitioners, who were all convicted of homicides as juveniles and sentenced, before Miller, to life without parole, challenged the validity of the sentences.[172] The petitioners asserted that although the sentencing schemes did not mandate life without parole, any sentencing procedures which did not distinguish between juveniles and adults violated Miller.[173] After determining that Miller applied retroactively,[174] the Court then had to decide whether Miller had implications for those sentenced under nonmandatory sentencing schemes.[175] Citing the line of previous cases, including Miller, Graham, and Roper, the Court concluded that the holding in Miller established that “youth has constitutional significance.” Because of this conclusion, the “failure of a sentencing court to consider the hallmark features of youth prior to sentencing that offends the Constitution.”[176] Although some of the petitioners’ proceedings did mention youth to various degrees, the Court held that none of these proceedings satisfied the constitutional requirements, creating “a facially unconstitutional sentence.”[177] Subsequently, the Supreme Court of South Carolina specified what juvenile sentencing courts must do to protect the rights of juvenile offenders.[178] Quoting the Supreme Court in Miller, the Supreme Court of South Carolina held that juvenile sentencing courts must consider

(1) the chronological age of the offender and the hallmark features of youth, including ‘immaturity, impetuosity, and failure to appreciate the risks and consequence’; (2) the ‘family and home environment’ that surrounded the offender; (3) the circumstances of the homicide offense, including the extent of the offender’s participation in the conduct and how familial and peer pressures may have affected him; (4) the ‘incompetencies associated with youth—for example, [the offender’s] inability to deal with police officers or prosecutors (including on a plea agreement) or [the offender’s] incapacity to assist his own attorneys’; and (5) the ‘possibility of rehabilitation.’[179]

Absent consideration of all of these factors, the Court determined that the proceedings violated the Constitution.[180]

As we reviewed the reasoning behind these holdings regarding youth in criminal contexts, one concern of both the Supreme Court of the United States and the Supreme Court of South Carolina is clear: absent additional protections, younger age groups may be punished for those same hallmarks of youth that make those same groups less culpable. Underdeveloped brains and personalities, lack of growth, and greater susceptibility to peer pressure and impulsivity all could predispose younger people to crime, which, in turn, might cause those in the criminal justice system to punish them disproportionately, particularly if the crime is viewed as heinous. Given the lack of research on such topics, and the explicit importance of parole in the treatment of youthful offenders, additional research examining both is merited.

Our hypothesis was simple: compared to those convicted of crimes when they are older, the Board will be significantly less likely to grant youthful offenders parole. We hypothesized that this result should exist even when controlling for other variables, such as race and biological sex. Further, building off of the limitations of previous research, we aimed to simulate a balanced experimental design, which should provide for a more accurate direct comparison of youthful and non-youthful offenders. Our hypothesis is primarily driven by the same concern vocalized by some researchers and the Supreme Court: that youthful offenders may be feared because they committed crimes earlier in their lives, regardless of the hallmarks of youth that may have predisposed them to committing their crimes. In addition, the COMPAS actuarial risk assessment measure used by the Board weighs youth as a factor that increases its predicted risk of violence.[181] The Board may see youthful offenders as “bad seeds” who are at higher risk to harm the public compared to adult offenders, absent specific procedures or protections to prevent such a conclusion.

Through the DPPPS, we acquired the information from all parole hearings between the years 2006 and 2016, a total of 44,148 records. This dataset included demographic data (such as a person’s identification number, name, age, race, and biological sex), the date of the parole hearing, the outcome of the hearing (as well as the associated release date), the person’s date of admission to SCDC, and information about the crime(s) that the person was convicted of (including the person’s indictment number), the dates of the offense and sentencing, the length of sentence,[182] the date the sentence started, the classification of crime(s),[183] and the maximum penalty allowed for the crime(s). It is important to note that SCDC and DPPPS provide their own separate and independent codes and descriptions for each crime. Because of this, there were rare occasions where conflicts arose or where DPPPS information was not provided (SCDC coding was always available). In case of conflict, DPPPS codes were used; this was because DPPPS information is based on their review of the file before the parole hearing. Additionally, to ensure that all offenses were accurately coded as violent or non-violent felonies, all DPPPS and SCDC offense codes and descriptions were manually checked with the South Carolina laws that were relevant at the time of the offense.

There are two other studies that have been published using part of this dataset. As mentioned earlier, Hritz narrowed her analyses to those who were convicted of murder and sentenced to life without parole.[184] As such, her sample size was just under 4,000 parole hearings.[185] In addition to this subset of the data, she obtained institutional records for those people included in her dataset.[186] Lastly, a key difference between this previous work and the current study is the analytical approach. Hritz analyzed changes in parole outcomes across time, including the different treatments of adults and juveniles before and after Miller and Graham were decided.[187] In contrast, the current study consists of a direct comparison of youthful (as opposed to juvenile) offenders and adults collapsing across time and while controlling for different variables. Additionally, the current study will involve propensity score matching, which attempts to simulate and randomized experimental design and will be described later.

The other recent study, conducted by the authors of this Article, used the full dataset to examine the presence of disparate outcomes by race or biological sex, as well as any interaction between the two.[188] Although this study did involve the full dataset, the objectives of these two studies (detecting sex-based and/or race-based disparity versus detecting age-based disparity) are categorically different. Further, although the previous study did control for age at the time of the offense when examining for disparity,[189] there was no variable examining a person’s status as a juvenile or youthful offender.[190] Lastly, unlike the current study, the previous study did not involve any matching.

There are a few important characteristics about the dataset that should be noted. Regarding race, over 98% of the hearings in the original dataset involved people who identified as racially white or Black. Because of this severe imbalance between racial groups, we decided to remove records for hearings involving people who identified as anything other than white or Black, reducing our sample size from 44,148 to 43,290 hearings.[191] This dataset also did not have any information on ethnicity, so that information could not be accounted for in our analyses.[192] Of the 43,290 hearings, 16,032 (37.0%) involved a white person; 27,258 (63.0%) involved a Black person. In terms of biological sex, 40,474 (93.5%) hearings involved a male; 3,674 (6.5%) involved a female. The average age for a potential parolee was 37.73 (11.77) years old.

Before our analyses, we first divided our sample into those who committed their first offense before the age of twenty-one (i.e., “youthful offenders”) and those who committed their first offense at or after the age of twenty-one. We chose this division because it allowed us to focus our examination of a possible effect of age on the earlier portion of the lifespan; in other words, we wanted to specifically examine whether the Board penalized youthful offenders compared to others. Due to the increased number of youthful offenders compared to juvenile offenders, this youthful division also afforded us greater statistical power for our analyses compared to dividing our sample on whether a person’s first offense was committed before the person turned eighteen.

To examine the potential effect of age on parole outcome, we ran a regression predicting whether the Board voted to grant or deny a particular person for parole.[193] In addition to our variable indicating whether a person would have been considered a youthful offender, we also controlled for the person’s race and biological sex, how much time the person had served at the time of the hearing, the number of murders that the person had been convicted of, the number of violent felonies (not including murders) that the person had been convicted of, the number of nonviolent felonies that the person had been convicted of, whether the person had been convicted of a subsequent offense while serving the current sentence, and the year that the parole hearing took place.[194] These variables were included in our analyses for several reasons: First, these variables (aside from the year of the hearing) have been used in literature on parole board decision making.[195] Second, and perhaps most important to practitioners, each of these variables (aside from the year of the hearing) are often referenced when advocating (or opposing) a person’s early release. Advocates will often emphasize the amount of time a person has served, a person’s criminal history, and/or whether a person has served the sentence without committing additional crimes. Lastly, the year of the hearing was included to control for time-related variance, such as minor policy changes, changes in board membership as terms expire, etc. Additionally, to control for potential bias caused by a person having multiple hearings during the ten-year span, we included the person’s ID in our model as a random effect.

To account for differences between our age groups on model variables, which may bias our results, we incorporated propensity score matching (PSM). PSM is a statistical method used to create quasi-experimental designs. These types of methods are often used when certain conditions (e.g., one’s gender, race, age group, etc.) are modeled that are unable to be randomly assigned. PSM attempts to reduce selection bias in observational data by matching participants on their propensity score.[196] The propensity score indicates the likelihood of being in the experimental group (i.e., a youthful offender in our study).[197] By matching subjects on their propensity score, the design becomes, at least partially, balanced, which should mimic a true randomized experimental design, the accepted gold standard of experimental research.[198]

Despite the advantages of dividing the sample based on youthful offender status, supplemental analyses dividing the sample based on juvenile offender status were also conducted as a robustness check. All our analyses were conducted in the statistical programming language R[199] and using RStudio.[200] General data processing and descriptive statistics were created using the R packages car,[201] dplyr,[202] and psych.[203] PSM was conducted using the MatchIt package.[204] Our logistic regression was conducted using lme4.[205]

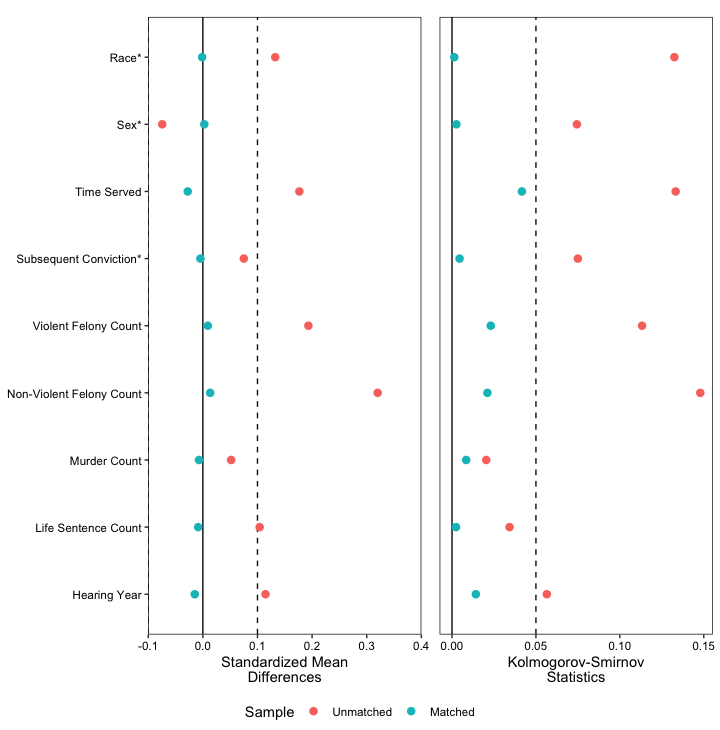

Balance of the covariates between the age groups after PSM was assessed using standardized mean differences in the covariates (the most common metric[206]) and the prognostic score, which has been found to outperform other metrics.[207] After PSM, we saw sufficient balancing between the groups. A visual representation of this balancing is shown in Figure 1. One drawback of using PSM is that the method requires removal of subjects that do not have a match in order to prevent imbalance between the groups.[208] As such, our overall sample size was reduced from 43,290 hearings to 19,164 hearings.[209] Demographics for this reduced sample, both overall and separated by our two age groups, are provided in Table 1. Descriptive statistics for all variables, both overall and separated by our two age groups, are provided in Table 2.

The results of our logistic regression post-PSM, using our matched and balanced sample, supported our hypothesis (see Table 3). A parole board was significantly less likely to grant parole to a youthful offender as opposed to someone who committed their first offense when twenty-one years of age or older. Specifically, parole boards were 18% less likely to grant parole to youthful offenders compared to the other group. Of our other predictors, parole boards were significantly less likely to grant parole to someone if that person was Black, served more time, had a greater number of convictions for non-violent or violent felonies (excluding murders), had a greater number of murder convictions, or had a greater number of life sentences. The only predictors in our model that increased the odds of parole were hearing year and biological sex. For the former, if the parole hearing took place more recently, then the Board was significantly more likely to grant parole. For the latter, parole boards were significantly more likely to grant parole to women compared to men.

As mentioned above, as a robustness check, we also ran a supplemental analysis using juvenile offenders, who committed their first offense(s) before turning eighteen, as opposed to youthful offenders, who committed their first offense(s) before turning twenty-one. Given the relatively smaller amount of juvenile, as opposed to youthful, offenders, this analysis had relatively lower statistical power. When matching juvenile offenders to others, our overall sample size was reduced from 43,290 hearings to 3,670 hearings (1,835 juvenile offenders and 1,835 others).[210] Using the same metrics as before, our matched sample was balanced. Demographics for this sample, both overall and separated by our two age groups, are provided in Table 4. Descriptive statistics for all variables, both overall and separated by our two age groups, are provided in Table 5

The results from this supplemental logistic regression analysis also supported our hypothesis (see Table 6). A parole board was significantly less likely to grant parole to a juvenile offender as opposed to someone who committed their first offense when eighteen years of age or older. For juveniles, the “youth tax” was more severe; parole boards were 28% less likely to grant parole to juvenile offenders compared to others. Unlike our previous analysis, there were relatively fewer significant predictors in this analysis other than juvenile offender status. Parole boards were significantly less likely to grant parole to people who served more time or who had a greater number of convictions for non-violent or violent felonies. Conversely, parole boards were significantly more likely to grant parole in more recent years (i.e., if the hearing year was closer to 2016). All other predictors were not statistically significant.

One Wednesday a month, the South Carolina Board of Paroles and Pardons holds up to sixty-five hearings for potential paroles.[211] Many of those seeking parole have worked for years, sometimes decades, to demonstrate rehabilitation and suitability for release back into society. For those who committed their crimes when they were younger, such as Stewart Buchanan, they may be simply trying to show that they are no longer the impulsive and underdeveloped youths of their past. For this group, “demonstrat[ing] growth and maturity,”[212] as described by the Supreme Court, is most important because the lack of such characteristics, at least in part, led to their incarceration in the first place. Nevertheless, despite all the work that is done, the overwhelming majority of potential parolees get denied each year.[213] And for some, especially those youthful offenders who have been denied multiple times, there is a fear that the “meaningful opportunity to obtain release”[214] that they were promised is only a mirage.

In this study, we used a decade of parole hearing data from South Carolina to compare the treatment of youthful offenders versus adult offenders. Using PSM, we were able to directly match almost all of our youthful offenders to adult offenders, creating a balanced comparison akin to the empirical “gold standard” of a randomized experimental design. Our results revealed a significant effect of youth, such that parole boards were 20% less likely to grant parole to youthful, compared to older, offenders. In supplemental analyses comparing juvenile versus non-juvenile offenders, this effect was magnified to nearly 30%. These results suggest, as researchers and the Supreme Court has feared in the past, that a non-significant number of people are being denied their freedom simply because of mistakes made as youths.

This study had several limitations, mostly related to the dataset. One major limitation was the lack of information regarding disciplinary records and participation in programming. Although PSM can help to simulate the balancing present in randomized experimental designs, the quality of the matching depends on the variables in the dataset. Accordingly, we are unable to rule out the chance that youthful offenders had a higher number of disciplinary violations and/or lower participation in institutional programming, both of which would be relevant to parole board decision making. Similarly, South Carolina is one of the few states that allows for the presence of an attorney during parole hearings.[215] Although it is unclear how many potential parolees have access to an attorney and how the mere presence of an attorney may affect parole outcomes, obtaining competent assistance in the creation of supportive briefs, compilation of materials, and other important aspects of parole hearing preparation may have a significant effect on parole hearing outcomes.

Another limitation of this study was the removal of racial groups that were neither white nor Black due to the extremely low sample sizes and suspect racial coding. This type of limitation is common in parole research.[216] Additional research examining the interaction between age effects and race may be fruitful, as it may elucidate whether age effects are similarly felt across different racial groups or if particular groups (e.g., young Black men) are more likely to be treated as “bad seeds” in parole hearings. Relatedly, our dataset lacked any information on Hispanic heritage, which may also affect the interpretation of any racial effects.

PSM also comes with its own share of limitations and criticisms.[217] Although many of these criticisms can be addressed by having a large sample and by checking balance metrics after PSM (both of which occurred in this study),[218] additional work using other matching methods may be worthwhile in this type of research. As mentioned earlier, as PSM can only address imbalance issues in observed confounds, there may be other variables of interest that were neither present in the dataset nor included in these models, such as the presence and quality of victim statements.

Overall, additional research is needed. The findings in this study suggested that, as the Supreme Court feared, those who committed their crimes when they were younger are not getting the benefits from their diminished culpability at the time of the offense or a recognition of their increased capacity for growth and rehabilitation. They, in the Court’s words, are not being afforded a “meaningful opportunity to obtain release . . . .”[219] To the contrary, being younger simply may indicate to the Board that the person is a “bad seed” in need of further incarceration. For people like Stewart Buchanan, the Board’s strategy is clear: If you truly deserved release as an adult, you should have never committed a crime as a child.

Tables

| Table 1

Demographics in the Matched Sample Broken Down by Age Group |

|||||

| M | SD | n | % | ||

| Overall | Age | 35.36 | 11.85 | ||

| Male | 18,693 | 97.5 | |||

| White | 5,119 | 26.7 | |||

| Convicted of Subsequent Offense | 14,143 | 73.8 | |||

| Granted Parole | 2,867 | 15.0 | |||

| Youthful Offender (n = 9,582) | Age | 30.01 | 9.43 | ||

| Male | 9,321 | 97.7 | |||

| White | 2,566 | 26.7 | |||

| Convicted of Subsequent Offense | 7,050 | 73.6 | |||

| Granted Parole | 1,303 | 13.6 | |||

| Non-Youthful Offender (n = 9,582) | Age | 40.71 | 11.60 | ||

| Male | 9,346 | 97.4 | |||

| White | 2,553 | 26.6 | |||

| Convicted of Subsequent Offense | 7,093 | 74.0 | |||

| Granted Parole | 1,564 | 16.3 | |||

Note. Age is referring to the age of the person at the time of the parole hearing.

| Table 2

Descriptive Statistics in the Matched Sample Broken Down by Age Group |

|||||||

| M | SD | Min. | Max. | Skew | Kurtosis | ||

| Overall | Time Served | 11.01 | 9.49 | 0.31 | 48.09 | 1.04 | 0.24 |

| Non-Violent Felony Count | 1.98 | 1.58 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 0.93 | 0.85 | |

| Violent Felony Count | 0.57 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 1.88 | 4.32 | |

| Murder Count | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 2.29 | 3.32 | |

| Life Sentence Count | 0.17 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 4.11 | 33.63 | |

| Youthful Offender (n = 9,582) | Time Served | 10.88 | 9.48 | 0.31 | 48.09 | 1.11 | 0.37 |

| Non-Violent Felony Count | 1.99 | 1.56 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 0.89 | 0.76 | |

| Violent Felony Count | 0.57 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 1.94 | 5.08 | |

| Murder Count | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 2.29 | 3.26 | |

| Life Sentence Count | 0.16 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 5.16 | 50.51 | |

| Non-Youthful Offender (n = 9,582) | Time Served | 11.14 | 9.49 | 0.36 | 45.67 | 0.98 | 0.12 |

| Non-Violent Felony Count | 1.97 | 1.61 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 0.96 | 0.92 | |

| Violent Felony Count | 0.57 | 0.88 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 1.83 | 3.63 | |

| Murder Count | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 2.29 | 3.37 | |

| Life Sentence Count | 0.17 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 2.64 | 7.04 | |

Note. Units for time served is years. Violent felony count does not include murders.

| Table 3

Logistic Regression Predicting Parole Outcome |

||||||

| Predictor | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | z | OR | |

| LL | UL | |||||

| Intercept | -2.290 | 0.103 | -2.492 | -2.088 | -22.224** | 0.101 |

| Youth Offender Status | -0.198 | 0.046 | -0.288 | -0.108 | -4.306** | 0.820 |

| Race | -0.256 | 0.051 | -0.356 | -0.157 | -5.034** | 0.774 |

| Sex | 0.873 | 0.125 | 0.628 | 1.117 | 6.998** | 2.393 |

| Time Served | -0.151 | 0.038 | -0.227 | -0.076 | -3.953** | 0.859 |

| Non-Violent Felony Count | -0.110 | 0.027 | -0.163 | -0.056 | -4.025** | 0.896 |

| Violent Felony Count | -0.439 | 0.036 | -0.509 | -0.368 | -12.197** | 0.645 |

| Murder Count | -0.253 | 0.070 | -0.391 | -0.116 | -3.163** | 0.776 |

| Life Sentence Count | -0.229 | 0.085 | -0.396 | -0.062 | -2.685** | 0.796 |

| Subsequent Conviction | -0.167 | 0.059 | -0.284 | -0.051 | -2.809** | 0.846 |

| Hearing Year | 0.101 | 0.008 | 0.086 | 0.116 | 13.108** | 1.106 |

Note. Race was coded such that a white person was coded as 0 and a Black person was coded as 1. Biological sex was coded such that a male was coded as 0 and a female was coded as 1. Time served, non-violent felony count, violent felony count, murder count, and life sentence count are all standardized. SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit; OR = odds ratio. * p < .05; ** p < .01.

| Table 4

Demographics in the Matched Sample with Juveniles |

|||||

| M | SD | n | % | ||

| Overall | Age | 34.92 | 12.25 | ||

| Male | 3,601 | 98.1 | |||

| White | 736 | 20.1 | |||

| Convicted of Subsequent Offense | 2,514 | 68.5 | |||

| Granted Parole | 459 | 12.5 | |||

| Juvenile Offender (n = 1,835) | Age | 30.08 | 9.74 | ||

| Male | 1,796 | 97.9 | |||

| White | 388 | 21.1 | |||

| Convicted of Subsequent Offense | 1,238 | 67.5 | |||

| Granted Parole | 196 | 10.7 | |||

| Non-Juvenile Offender (n = 1,835) | Age | 39.76 | 12.58 | ||

| Male | 1,805 | 98.4 | |||

| White | 348 | 19.0 | |||

| Convicted of Subsequent Offense | 1,276 | 69.5 | |||

| Granted Parole | 263 | 14.3 | |||

Note. Age is referring to the age of the person at the time of the parole hearing.

| Table 5

Descriptive Statistics in the Matched Sample with |

|||||||

| M | SD | Min. | Max. | Skew | Kurtosis | ||

| Overall | Time Served | 12.76 | 9.89 | 0.43 | 44.31 | 0.79 | -0.42 |

| Non-Violent Felony Count | 1.87 | 1.57 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 0.91 | 0.77 | |

| Violent Felony Count | 0.70 | 0.94 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 1.79 | 4.42 | |

| Murder Count | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.47 | 0.15 | |

| Life Sentence Count | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 1.97 | 3.76 | |

| Juvenile Offender (n = 1,835) | Time Served | 12.85 | 9.82 | 0.57 | 43.40 | 0.83 | -0.35 |

| Non-Violent Felony Count | 1.84 | 1.53 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 0.90 | 0.68 | |

| Violent Felony Count | 0.71 | 0.94 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 1.94 | 5.80 | |

| Murder Count | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.40 | -0.04 | |

| Life Sentence Count | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | |

| Non-Juvenile Offender (n = 1,835) | Time Served | 12.67 | 9.96 | 0.43 | 44.31 | 0.76 | -0.48 |

| Non-Violent Felony Count | 1.96 | 1.60 | 0.00 | 9.00 | 0.91 | 0.83 | |

| Violent Felony Count | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 1.64 | 2.98 | |

| Murder Count | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.53 | 0.35 | |

| Life Sentence Count | 0.23 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 1.93 | 3.34 | |

Note. Units for time served is years. Violent felony count does not include murders.

| Table 6

Supplemental Logistic Regression Predicting Parole Outcome After Propensity Score Matching with Juvenile Offenders |

||||||

| Predictor | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | z | OR | |

| LL | UL | |||||

| Intercept | -2.327 | 0.192 | -2.703 | -1.952 | -12.141** | 0.098 |

| Juvenile Offender Status | -0.331 | 0.103 | -0.533 | -0.129 | -3.213** | 0.718 |

| Race | -0.169 | 0.130 | -0.424 | 0.087 | -1.296 | 0.845 |

| Sex | 0.304 | 0.361 | -0.403 | 1.011 | 0.842 | 1.355 |

| Time Served | -0.220 | 0.091 | -0.399 | -0.041 | -2.406* | 0.803 |

| Non-Violent Felony Count | -0.153 | 0.065 | -0.281 | -0.026 | -2.364* | 0.858 |

| Violent Felony Count | -0.418 | 0.077 | -0.569 | -0.266 | -5.408** | 0.659 |

| Murder Count | -0.285 | 0.152 | -0.583 | 0.012 | -1.879 | 0.752 |

| Life Sentence Count | -0.065 | 0.157 | -0.374 | 0.243 | -0.415 | 0.937 |

| Subsequent Conviction | -0.063 | 0.130 | -0.318 | 0.192 | -0.486 | 0.939 |

| Hearing Year | 0.087 | 0.017 | 0.054 | 0.119 | 5.171** | 1.091 |

Note. Race was coded such that a white person was coded as 0 and a Black person was coded as 1. Biological sex was coded such that a male was coded as 0 and a female was coded as 1. Time served, non-violent felony count, violent felony count, murder count, and life sentence count are all standardized. SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit; OR = odds ratio. * p < .05; ** p < .01.

Figures

Figure 1

Love Plot Visualizing the Balancing Results of PSM

Note. Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) Statistics and mean differences are two accepted metrics for assessing whether PSM resulted in a balanced dataset.[220] Respective cut-offs for acceptable KS Statistics and mean differences are displayed as dotted lines. * indicates variables for which the graphed mean difference value is the raw (unstandardized) difference in means, as opposed to the standardized difference in means.